By Jonas Jessen, Postdoctoral Researcher at German Institute for Employment Research (IAB), Robin Jessen, head of the research group “Microstructure of Taxes and Transfers” and researcher at the Department of Macroeconomics and Public Finance at RWI – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research in Berlin, Andrew C. Johnston, Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, Merced and a Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and Ewa Gałecka-Burdziak, Associate Professor at SGH Warsaw School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU.

As governments worldwide grapple with labour shortages and systemic budget shortfalls, the question arises of how unemployment insurance policies potentially contribute to this imbalance by increasing and extending nonemployment. This column argues that recent debates around unemployment insurance reform, which often focus on the effect among job seekers, overlook potential unintended consequences among the employed. Taking moral hazard among employed workers into account has substantial effects on the welfare implications of unemployment insurance.

Traditional analyses of unemployment insurance (UI) systems examine how benefit generosity affects job search behaviour and unemployment duration. Recent research by Bell et al. (2024) and Landais (2015), for example, demonstrates that more generous benefits lead to longer unemployment spells. However, these studies capture only part of the story by focusing on the unemployed alone.

Our research (Jessen et al. 2025) reveals a previously underexplored dimension: UI generosity also significantly influences currently employed workers’ behaviour. Using unique policy discontinuities in Poland’s unemployment insurance system, we find that higher UI benefits not only extend unemployment spells but can actually increase transitions into unemployment, particularly when benefits are both generous and long-lasting.

The Natural Experiment: Poland

Poland’s UI system provides an ideal setting to study these effects through two distinct policy features:

- Potential benefit duration: Claimants receive 12 months of benefits instead of six if local unemployment exceeds a certain threshold (Jessen et al. 2023)

- Benefit level: Workers receive 25% higher monthly benefits after reaching five years of covered employment

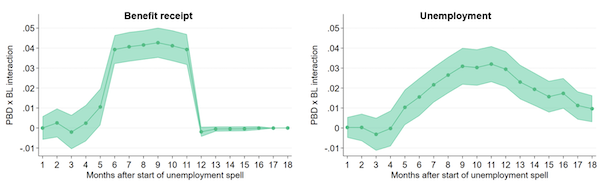

These clear cut-offs create natural comparison groups on either side of each cut-off, allowing us to measure how UI generosity affects outcomes for both employed and unemployed workers. Figure 1 illustrates the potential benefit duration (PBD) variation by plotting average benefit and unemployment duration around the threshold where the potential benefit duration increases by six months.

Figure 1 Benefit and unemployment duration around the PBD threshold

Notes: Figures show months in benefit receipt an in unemployment in bins of percentage point of county’s relative employment rate.

Key Findings

Leveraging the policy variations in the Polish UI system, we find that increasing benefit levels or benefit durations by 10% both lead to a 3% increase in unemployment duration. As extending benefit durations has a larger impact on total benefits paid, this comes with a higher direct cost for taxpayers.

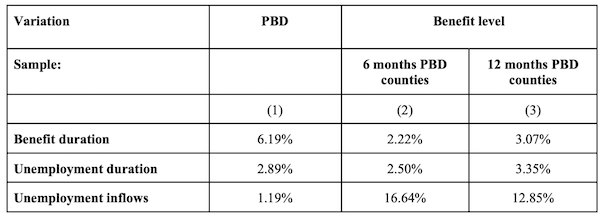

As the variation in benefit levels and benefit duration is independent, the setting allows us to provide novel insights into how the two key parameters of UI generosity interact. In a two-way regression discontinuity design, we find that the effect of benefit level increases is substantially larger when the benefit duration is also extended. In Figure 2, we present monthly estimates of the level-duration interaction, showing that this amplifying effect materialises after benefits expire under the less generous regime (the coverage effect; see Bell et al. 2024). The positive interaction suggests that the moral hazard costs of increasing benefit levels are substantially amplified when workers have access to longer benefit durations.

Figure 2 Monthly estimation of the benefit-duration-level-interaction term of two-way regression discontinuity estimates

Note: Figure shows monthly RD estimates of the interaction term of PBD extensions and benefit level (BL) increases. Shaded areas indicate 85% confidence intervals.

We also study whether a more generous UI can improve workers’ long-term prospects by improving job match quality as documented by Kugler et al. (2021) and Weber and Nekoei (2015). Tracking workers over five years after their initial unemployment spell we find no evidence that workers benefit from more stable job matches as we find no decreased unemployment probability over the five-year horizon.

We move on to examine whether unemployment insurance creates moral hazard among employed workers by increasing transitions into unemployment. A 10% increase in potential benefit duration leads to a modest increase of 1.2% in unemployment inflow. Yet, strikingly, a 10% increase in benefit level generates a substantially larger increase in unemployment inflows of 13-17%.

A summary of the effects of increases in benefit levels and durations is presented in Table 1. The large difference in inflow effects suggests that increasing benefit levels generates larger distortions among the employed.

Table 1 Effects of a 10% increase in UI generosity

Policy Implications

Our findings have profound implications for UI policy design. The traditional focus on balancing consumption smoothing against job search incentives misses a crucial aspect: the effect on employed workers’ behaviour. Our welfare analysis suggests that accounting for this ‘employed worker moral hazard’ dramatically changes the cost-benefit calculation of UI policies.

For instance, in the standard model that only considers unemployed workers’ behaviour, the cost of transferring $1 to the unemployed through higher benefits is about $2.3 in behavioural distortions. However, when we extend the canonical models for welfare analysis to include the effect on employed workers, this cost rises to over $10, primarily due to increased transitions into unemployment. For benefit extensions the behavioural distortions increase from $2.5 to $3.6.

This does not mean UI benefits should be eliminated – they play a crucial role in providing economic security and enabling effective job search. However, policymakers should consider (1) reducing the benefit level while increasing benefit durations, as they create fewer distortions and provide more value to those truly in need; and (2) experimenting with insurance programmes that mitigate moral hazard by either paying claims as a lump sum or using unemployment insurance savings accounts that reward workers when they avoid unemployment (Feldstein and Altman 2007).

Looking Forward

As workforces age and budget liabilities come due, understanding these complex policy interactions becomes increasingly important. Our findings suggest that optimal UI policy requires a more comprehensive approach than previously thought. While providing adequate support for the unemployed remains valuable, policymakers must also consider how benefit structures affect social welfare by their effects on employment and output, which shapes overall welfare.

References available at the original.