BBC

BBCAfter nearly two decades of student loan payments, Angela Carpio, 40, thought the finishing line was in sight.

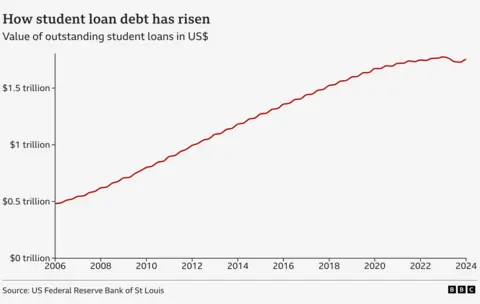

But now she’s caught in the middle of a political tug of war over a $1.74tn (£1.31tn) mountain of student debt held by 45 million Americans, most of it owed to the federal government.

For borrowers like Angela, a mother-of-two and software developer who lives near Minneapolis, Minnesota, the logjam has upended family budgets and made it difficult to plan.

November’s election, in which two candidates with starkly different visions for handling the debt are running neck-and-neck, is only adding to the sense of insecurity.

Angela took out her first student loans in 2001, eventually borrowing about $25,000 as she attended the for-profit DeVry University in Florida before earning an associate degree at Valencia College.

Despite making steady payments, her balance is still stuck at more than $20,000 as interest racks up.

“I’m just in limbo,” she says. “I don’t know what’s going to happen and it scares me.”

Since the 1990s, the US has offered some borrowers the option to repay student loans using a process similar to the UK, where bills are based on a proportion of a borrower’s income and the debt is written off after 25 years.

But participation in the US repayment plan remained low, partly because of limited awareness.

President Joe Biden, initially a sceptic of loan forgiveness, made it a signature policy for his administration, aiming to shore up support among younger voters, who are most likely to hold debts and rate the issue as important.

Vice-President Kamala Harris, now the Democratic presidential nominee, has pledged to continue his efforts.

Under Biden, the government has wiped out more than $168bn in debt for over 4.7 million borrowers, over a million of them lower-income Americans. That’s more loan forgiveness than any other president.

But the US Supreme Court last year struck down the White House’s most sweeping proposal – to cancel $400bn in student loans for 16 million borrowers – ruling it was an illegal use of executive power.

A second Biden plan called Save (Saving on a Valuable Education) – which offered lower monthly loan payments – is on hold pending federal court review.

Republican officials have led the legal challenges, arguing the debt write-off is unfair to the vast majority of Americans who did not take out student loans.

But supporters of the White House policy say they are merely trying to fix problems that they argue have unfairly deprived borrowers of relief.

In the meantime, the court setbacks have caused head-spinning bureaucratic headaches for precisely those Biden was trying to help.

Angela had enrolled in Biden’s Save payment plan, which promised to cut the $400 or so she owed each month roughly in half and cancel her debt after 20 years.

While the legal challenge has halted her payments – for now – she said the temporary reprieve has only stoked her worries about what comes next.

“It’s just a mess,” she said. “It’s very confusing and very hard to plan when the most concrete things are no longer there.”

Veronica Williams

Veronica WilliamsThe US put student loan payments on hold during the pandemic. As of January, a few months after payments resumed, only half of debtors were up to date on their bills.

Veronica Williams, a 32-year-old from Sacramento, California, has $127,000 in student debt after earning a college and a master’s degree.

But the court battles have also left her loan up in the air, and she says she cannot even get answers about what she owes for her monthly payment.

Veronica, who works for the Department of Veterans Affairs, backed Biden in 2020, but said she was still waiting to decide if she would support Democrats again.

“There’s no clear understanding on what we’re supposed to do,” she said of her loan situation.

“It’s disheartening because it feels like it leaves me and my friends and colleagues confused on what the future… is going to be for us.”

On the campaign trail, Harris, while promising support for forgiveness, has not spotlighted the issue.

Donald Trump, meanwhile, has argued that Democrats have “taunted” borrowers with hope while failing to deliver.

At the same time, the Republican presidential nominee has condemned student debt forgiveness as “vile”.

For Republicans, who have seen college-educated and younger voters shift decisively to Democrats in recent years, the risks of opposing cancellation are minimal, said Anthony Fowler, a professor at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy.

For Democrats, it remains to be seen whether student loan forgiveness will help or hurt.

A June UChicago Harris/AP-NORC poll found just 30% of Americans approved of Biden’s handling of the issue, though Republicans and the Supreme Court fared even worse.

Prof Fowler said he thought embracing debt forgiveness could backfire for Democrats, noting that less than 40% of US adults over age 25 hold college degrees and research has found sweeping forgiveness would benefit households with higher-than-average incomes.

“The politics of asking your plumber to pay for your kids’ fancy liberal arts degree – this doesn’t make a lot of sense,” he said.

Robert Henley

Robert HenleyBut Mallory SoRelle, professor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, noted that an estimated one-third of Americans with student debt did not graduate and that polls indicate significant support among Democrats and independents for at least some relief.

“If [Biden’s plans] actually had gone through in a timely manner, I think we would see a much bigger boost for Democrats, but this is an issue that voters still say they care about,” she said.

Robert Henley, a 68-year-old public sector retiree from Tallahassee, Florida, voted for Trump in 2016 and Biden in 2020.

He said he opposed debt forgiveness as too costly to the government and unfair to taxpayers like him and his wife who had sacrificed to save for their children’s education.

But he said he expected to vote for Harris in November anyway, citing other concerns – such as his mistrust of Trump.

“As a country, we cannot afford to be giving away money – but really more importantly from my point of view, it’s unfair,” he said. “Obviously as a voter you can’t have every single issue fall out the way you want it.”