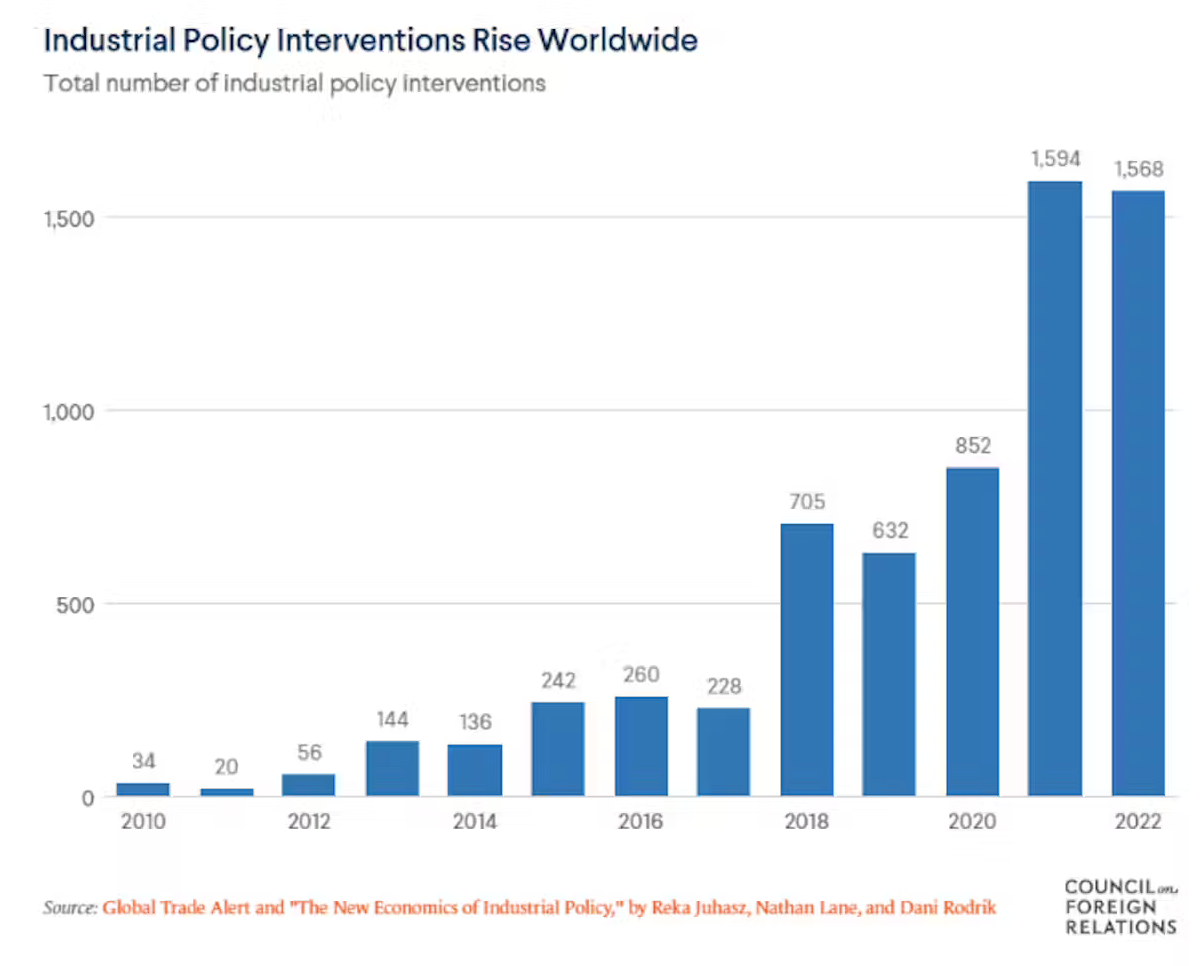

Yves here. This post is useful by virtue of giving some detail on how the Smoot Hawley Act made the Great Depression worst. However, it also takes an absolutist view against tariffs, when some well-regarded development economists like Dani Rodrik would beg to differ with some of its claims. In the last 15 years or so, this cohort has argued that tariffs are beneficial to less advanced economies when implemented so as to protect certain industries so they can get to be big and efficient enough to have a hope of competing in world markets.

It is also worth noting that non-tariff trade barriers can be very effective….and hard to curb. The poster child is Japan in the 1970s and 1980s. Aside from the difficulty of navigating a very fragmented distribution system serving as an impediment to foreign vendors, at least as big an obstacle was the strong Japanese preference for Japanese products. They regarded US wares as inferior, and the proof went beyond cars. I would see Japanese women in stores turn garments inside out to count the number of stitches per centimeter, and American clothing fell short.

The Plaza and then Louvre Accords demonstrated the doggedness of these preferences. The Plaza Accord was G-5 agreement to engage in coordinated currency manipulation to increase the value of the yen v. the dollar. The program succeeded too well, leading to a big overshoot in the value of the yen, resulting in the Louvre Accord to bring the yen back down.

The US expected the Plaza Accord to reduce the level of Japanese imports into the US, particularly cars, by virtue of making them more expensive, and also increase US exports to Japan because, conversely, their price would be lower.

While Japanese exports to the US did indeed drop meaningfully, US exports to Japan barely budged.

By Deniz Torcu, Adjunct Professor of Globalization, Business and Media, IE University. Originally published at The Conversation

Imagine waking up in 1932, in any US city. Upon ordering your morning coffee, you realise that its price has doubled since last year. This isn’t because of a coffee shortage, but rather because new trade barriers have caused the price of importing Colombian coffee beans to shoot up. The same thing has happened to sugar, tea and cocoa. Everyday items have suddenly become a luxury.

This dramatic change stemmed from one of the most harmful decisions in modern economic history: the Smoot-Hawley Act, enacted in June 1930. This law, championed by senator Reed Smoot and congressman Willis C. Hawley, aimed to safeguard US agricultural interests in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash.

However, pressure from industry lobbies meant it quickly expanded to cover over 20,000 products, including manufactured goods. Tariffs averaged around 40%, but in some cases were as high as 100%.

Far from helping the economy, this measure contributed to the collapse of international trade, as countries like Canada, France, Italy, Germany and the UK imposed harsh retaliatory tariffs on on US products. This set off a chain reaction: international cooperation weakened, US exports fell by 61% between 1929 and 1933, and global trade shrunk by over 60%.

This further aggravated the Great Depression. It hit economies who depended on international trade especially hard, and exacerbated geopolitical tensions throughout the 1930s.

Skyrocketing inflation, mass job destruction and falling living standards became stark testaments to protectionism’s failure. The contraction of global trade not only crippled key industries, but also destabilised entire economies that depended on exports to sustain growth. Currencies were devalued, deficits soared, and financial systems collapsed one after the other.

The 1930s therefore witnessed not only an economic crisis, but also a transformation of the international system fuelled, in part, by misguided political and trade decisions. This historical lesson, as the current case of Trump’s tariffs demonstrates, continues to be ignored by leaders who prioritise short-term populist measures over global economic stability.

Why Do Tariffs Fail?

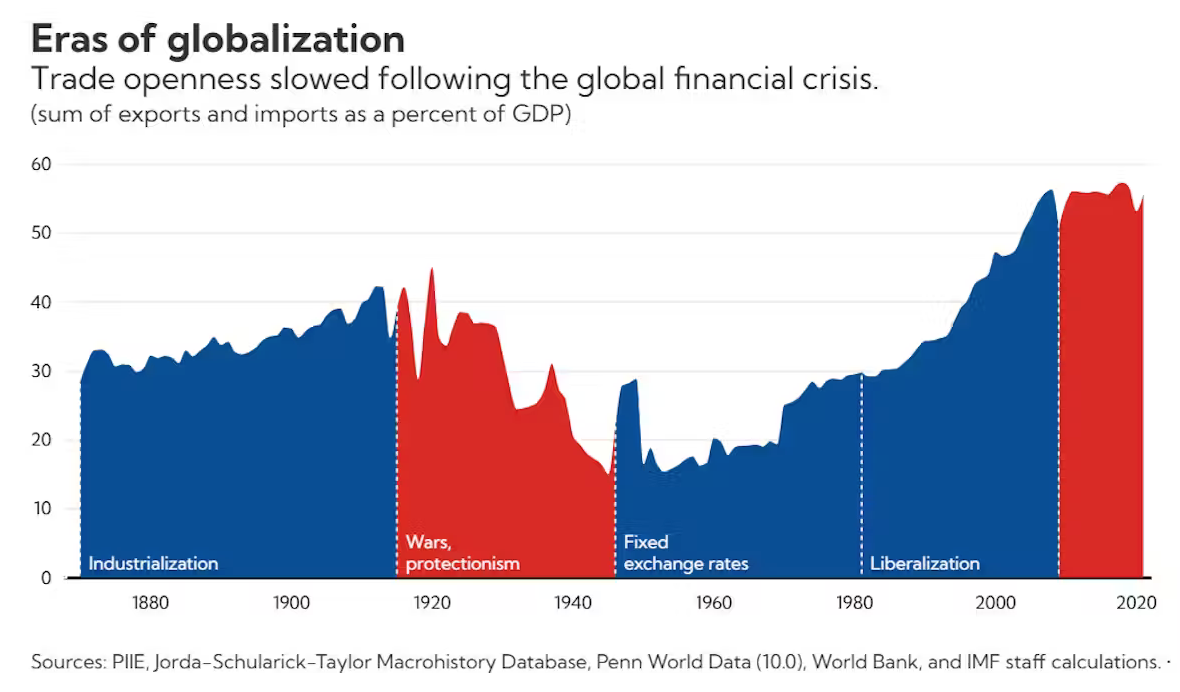

After decades of progress in trade liberalisation – driven by multilateral organisations like the World Trade Organization, the United Nations and the OECD – it seemed that lessons had been learned. However, Donald Trump’s second presidential term has revived disturbing parallels with Smoot-Hawley.

Historical and contemporary evidence clearly shows that tariffs rarely function as an effective tool of economic protection. In an interdependent global system, supply chains cross multiple borders before reaching the final consumer. Higher tariffs raise production costs, hurting both consumers and businesses, even in the countries that implement them.

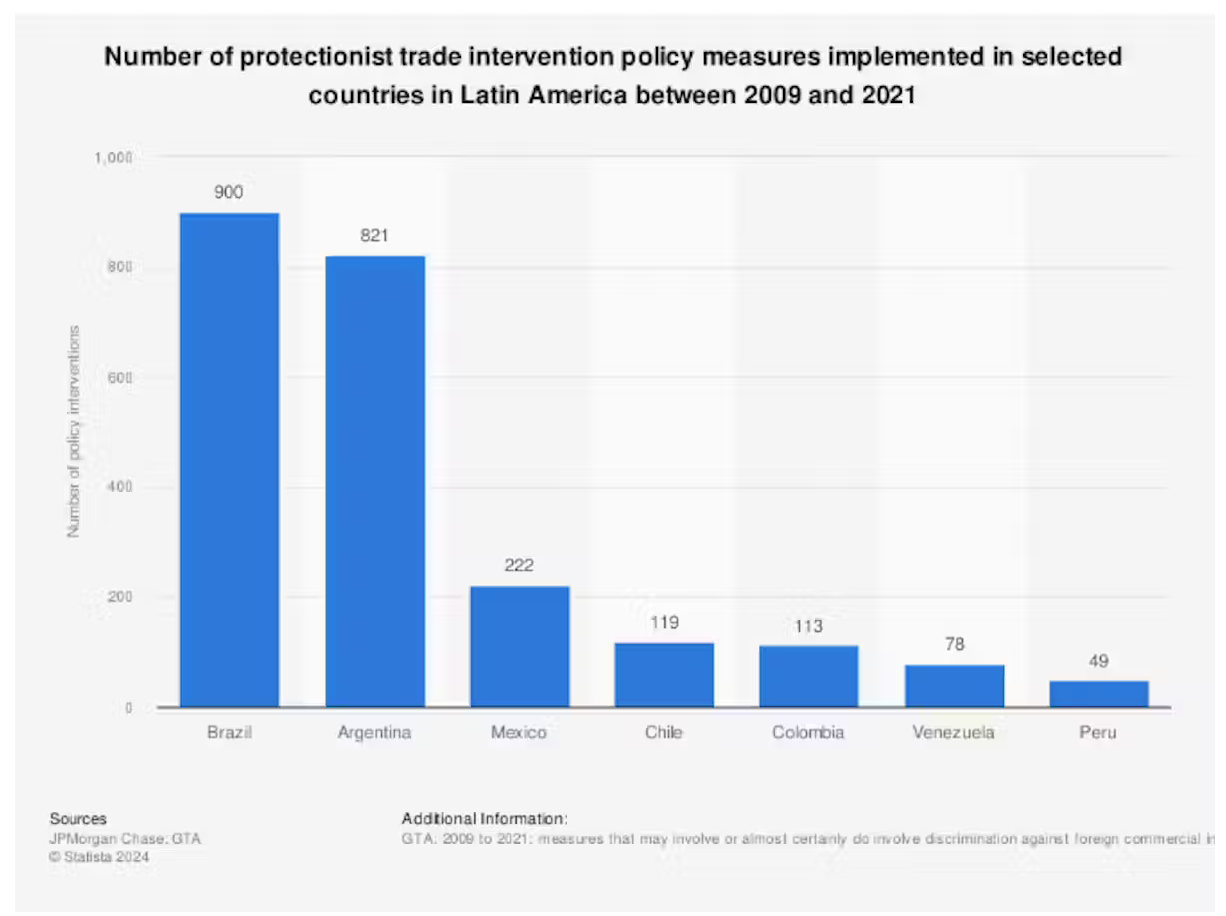

In addition to the US, other countries have also felt the adverse effects of protectionism. Argentina, for instance, implemented an import substitution policy with high tariffs and trade restrictions for decades. Although it initially stimulated industrial development, in the long run it led to a loss of competitiveness, high inflation and dependence on the state to prop up inefficient sectors.

Brazil had a similar experience in the 1980s and 1990s. Its tariff barriers temporarily protected certain industries, but also reduced product quality and stifled technological innovation.

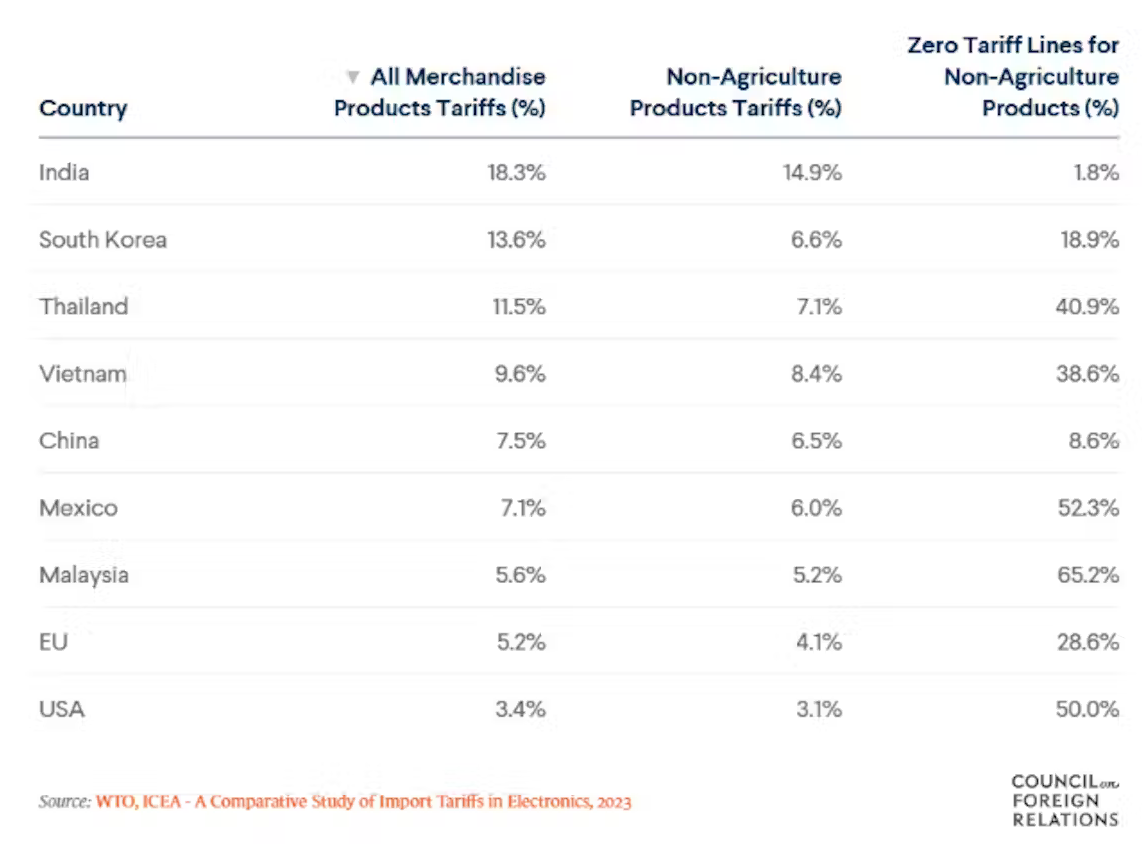

Until its 1991 economic reforms, India had one of the world’s most protectionist tariff regimes, which limited its integration into global trade and slowed its economic growth.

From these examples we can see that protectionism often causes a chain reaction of negative, escalating impacts:

- Rising prices for consumers

- Loss of economic competitiveness and job destruction

- Reduction of global economic growth due to uncertainty and diminished international trade.

Making Economies More Cooperative and Resilient

From the Smoot-Hawley Act to Trump’s current trade war, economic history clearly demonstrates that protectionism is not only ineffective, but counterproductive. In a world where value chains are global and innovation depends on transnational cooperation, closing economic borders weakens collective resilience.

Protectionism may seem like an immediate solution to economic crises and domestic pressures, but its long-term consequences are almost always more costly than its apparent benefits. Instead of strengthening domestic industries, it isolates them. Instead of protecting jobs, it destroys future opportunities.

The aforementioned cup of coffee in 1932 became a symbol of an economy locked in on itself. In 2025, it could be electric car batteries, medicines or basic foodstuffs that remind us of the high cost of negatively interfering in global trade.

Now more than ever before, international cooperation, market diversification and investment in sustainable competitiveness are the only smart way forward.