Yves here. The modest headline claim about oil prices and inflation seems reasonable, if nothing else due to lead and lag effects, as well as the ability of businesses and consumers to a degree to curtail energy use when prices rise.

However, the CEPR paper summarized in this article contends that oil prices don’t have as much impact on inflation as conventionally assumed, and bases that claim on an analysis of retail gas prices v. consumer inflation.

Due to the hour, I confess to not having read the underlying CEPR study. However…huh? First, due to changes in refining spreads over time, changes in oil prices no way, no how change in a 1:1 relationship to prices at the pump.

Second, gas is the most heavily consumed petroleum product in the US, at 44% of the total in 2021. I was not able to find a breakdown of consumer versus commercial/municipal use. But keep in mind the per vehicle disparity is large:

It has been widely reported that increases in gas prices to truckers has an impact on end product costs, particularly food.

Similarly, higher oil prices are regularly correlated with, and used to justify, much higher airfares.

Admittedly, the CEPR study falls back on its use of “core inflation,” derived from CPI and the personal consumption expenditures, so one can argue that it is narrowly correct in using consumer-related figures all around. But the Fed reliance on comparatively few and much jiggered key metrics is questionable.

I will ask my mavens what they think of this work.

By Alex Kimani, a veteran finance writer, investor, engineer and researcher for Safehaven.com. Originally published at OilPrice

- A new study has found that high gas prices have a much lower impact on U.S. core inflation than earlier assumed.

- U.S. inflation has been falling since mid-2022 and currently stands at a more palatable 6.5%.

- Much of the increase in inflation triggered by rising crude prices occurs in the first month after the rise in crude prices but is only short-lived.

For decades, the conventional wisdom in macroeconomics has been that high oil and gas prices are frequently the leading cause of high inflation. In fact, many analysts have blamed the two major oil price shocks of the 1970s for high inflation during the decade. The argument has been that oil prices and inflation are connected in a cause-and-effect relationship, therefore, as oil prices climb, inflation tends to follow in the same direction higher and vice-versa. This is supposedly the case because oil is a major input in the economy, and if input costs rise, so should the cost of end products.

But a new study has found that high gas prices have a much lower impact on U.S. core inflation than earlier assumed. A deep dive into the latest wave of high inflation in the United States reveals that the relationship between high energy prices and inflation is hardly straightforward nor is it supported by available data.

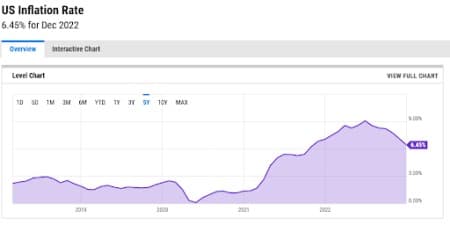

After an incessant climb to multi-decade highs, U.S. inflation has been falling since mid-2022 and currently stands at a more palatable 6.5%.

Source: Y-Charts

According to a study by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), the share of motor-fuel spending in the consumer basket in the U.S. is ~4%, far less than the shares for food or shelter. Moreover, a 1% increase in the price of crude translates to a mere 0.6% increase in the price of gasoline, further lessening the impact of crude prices on inflation.

CEPR goes on to say that much of the increase in inflation triggered by rising crude prices occurs in the first month after the rise in crude prices but is only short-lived.

According to CEPR, past attempts at quantifying the inflationary effects of energy price shocks often relied on empirical methods that have been demonstrated to be invalid.

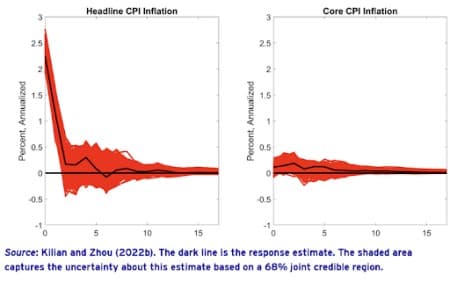

By using state-of-the-art vector autoregressive models, however, the organization has found that whereas a one-time unexpected increase in gasoline prices does cause a sharp increase in U.S. headline consumer price inflation (CPI), the response only persists for two months before becoming indistinguishable from zero.

CEPR concludes that there is no evidence of persistent increases in inflation due to rising gasoline prices or of delayed periodic inflation spikes, as wages are renegotiated.

Source: CEPR

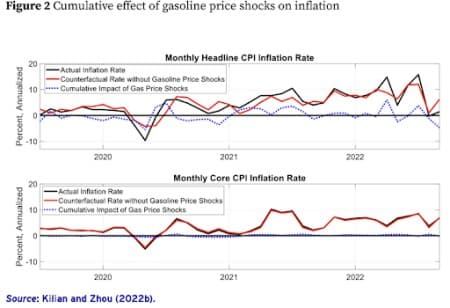

So, how would U.S. inflation have evolved after June 2019 if gas prices had remained at previously low levels? Well, CEPR has modeled this and found that inflation would only be moderately lower. For instance, in May 2022, higher gas prices added ~1.2 percentage points to the 12-month headline consumer price index inflation rate compared with an actual rate of 8.5%, an impact CEPR says can be safely ignored.

Source: CEPR

U.S. Deflation

There’s an emerging school of thought that says that economists should be more worried about possible deflation in the U.S. rather than the current inflation.

Last February, maverick stock picker Cathie Wood of ARK Invest(NYSEARCA: ARKK) told a webinar that advances in technology will likely push productivity rates higher, outweighing any gains in wages.

“We have a very strong point of view that productivity gains we will witness over the next five to 10 years will be astonishing. We think productivity will increase 5%-plus, and we won’t have an inflation problem,” she said.

Wood remains one of the few prominent fund managers who say that deflation, rather than inflation, will be a driving force in the U.S. economy and stock market over the next few years. ARK Invest has become famous for being something of a contrarian by betting on high-valuation, high-growth stocks that soared during the early stages of the pandemic.

Back in December, in an opinion piece in Politico, Dartmouth College economics professor David Blanchflower called the Fed’s reliance on interest rate hikes “guessenomics on zero data”, further predicting that a period of deflation might be the end result. EasyKnock Inc. CEO Jarred Kessler says that deflation may be at hand, telling Benzinga, “I haven’t seen real deflation in my or my parents’ lifetime, but as bad as the economy we’re looking at is, we may experience a deflationary period ahead.”

According to Kessler, government stimulus programs are to blame for the current economic woes, and people will start drawing on their home’s equity again because “there aren’t a lot of options left” after credit card debt recently surged to 18-year high.

Another jarring sign: Bloomberg says the rental markets could be deflating, with home and apartment rental markets having dropped sharply over the past 90 days while vacancies are rising.