Yves here. This paper provides yet another lens into the deterioration of civic values in the US and the more-related-than-you’d-think difficulties the US is having meeting military recruitment goals, In the UK, there’s a solid correlation between per capita WWI losses in the UK and various pro-social activities….including enlistment for WWII. The authors posit a big reason for that outcome is that these communities, and the country as a whole, commemorated the loss of these young men in war.

When I was in Australia, I was struck at how serious (in the early 2000s) Anzac day was, even though the underlying event was a close to a debacle. From Wikipedia:

In 1915, Australian and New Zealand soldiers formed part of an Allied expedition that set out to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula to open the way to the Black Sea for the Allied navies. The objective was to capture Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, which was an ally of Germany during the war. The ANZAC force landed at Gallipoli on 25 April, meeting fierce resistance from the Ottoman Army commanded by Mustafa Kemal (later known as Atatürk).[8] What had been planned as a bold strike to knock the Ottomans out of the war quickly became a stalemate, and the campaign dragged on for eight months. At the end of 1915, the Allied forces were evacuated after both sides had suffered heavy casualties and endured great hardships.

The entry continues to describe how the campaign became a defining event for both young nations:

Though the Gallipoli campaign failed to achieve its military objectives of capturing Constantinople and knocking the Ottoman Empire out of the war, the actions of the Australian and New Zealand troops during the campaign bequeathed an intangible but powerful legacy. The creation of what became known as an “Anzac legend” became an important part of the national identity in both countries. This has shaped the way their citizens have viewed both their past and their understanding of the present. The heroism of the soldiers in the failed Gallipoli campaign made their sacrifices iconic in New Zealand memory, and is often credited with securing the psychological independence of the nation.

Similarly, as many readers know, Russia continues to honor the memory of the very many who died in World War II via “Immortal Regiment” ceremonies.

By contrast, with the Iraq War, the US started trying to pretend our conflicts had no human cost. I recall military families being upset that videos of soldiers returning home in coffins suddenly were verboten on TV, when in the past these sacrifices were honored.

By Felipe Carozzi, Associate Professor of Urban Economics and Economic Geography in the Department of Geography and Environment London School Of Economics And Political Science; Edward Pinchbeck, Birmingham Fellow, Birmingham Business School University Of Birmingham; and Luca Repetto, Associate Professor Uppsala University. Originally published at VoxEU

Countries currently involved in active warfare – Ukraine, Russia, and Israel most prominently – have launched intense mobilisation campaigns to expand their armies. This column examines what compels ordinary men and women to fight. Specifically, the authors study how the memorialisation of British soldiers who died in WWI affected civic capital in the communities they came from, and whether that spirit shaped the behaviour of soldiers in WWII. Subsequent generations of soldiers from those communities were more likely to also give their lives in battle, and to be commended with military honours.

Data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program indicate that 2022 was the year with the largest number of fatalities in state-based conflicts in over three decades. According to the Global Peace Index, produced by the Institute for Economics & Peace, the world has become progressively less peaceful over the last 15 years. Countries currently involved in active high-intensity warfare such as Ukraine, Russia, and Israel have launched intense mobilisation campaigns to expand their armies with fresh recruits. What motivates these men and women to fight, to take often fatal risks on the battlefield?

The actions of individuals in war pose a paradox for social scientists, especially for economists. Combat represents a topical example of a collective action problem, whereby most benefits from fighting accrue to a third-party – for example, the nation – while costs fall squarely on those who fight, particularly those who die (Campante and Yanagizawa-Drott 2015). It is therefore hard to rationalise the behaviour of soldiers in battle as motivated by pecuniary cost/benefit calculations. Yet, nations have long found individuals willing to engage in combat. A series of recent papers in economics and political science attempt to understand what motivates them to fight. Studies have focused on different drivers such as propaganda (Barber and Miller 2019), religious and cultural beliefs (Beatton et al. 2019), public recognition (Ager et al. 2021), and state repression (Rozenas et al. 2022), among other factors.

In a recent discussion paper (Carozzi 2023), we turn to this question by studying how past deaths in combat affect a community’s values and, through those values, how they shape combat motivation for the next generation of soldiers. Specifically, we study how the deaths of soldiers who fought in WWI affected civic capital in the communities these soldiers came from and, through this effect, shaped the behaviour of soldiers in WWII. For this purpose, we conduct an empirical analysis that focuses on the British experience in the two World Wars.

Great War Remembrance in the UK

Over 700,000 British servicemen died fighting in WWI, making it by far the deadliest war in the long history of the British Army. This severe shock triggered a wave of commemoration and remembrance that became a characteristic feature of British life to this day. A day of remembrance, instituted in 1919 to commemorate the Armistice of 11 November 1918, has been celebrated every year since with parades and ceremonies. The ceremonial laying of wreaths at the Cenotaph in Whitehall on Remembrance Day 2022 was one of the first public acts of King Charles III after his coronation. It is around this Remembrance Day that the Poppy Appeal is still held annually, with over 30 million of the well-known commemorative poppies produced by the Poppy Factory each year.

In Great Britain alone, over 50,000 war memorials were built after WWI (IWM 2024). These monuments can still be found in towns and villages throughout the country and were often built using funds raised by local communities. They serve as tangible symbols of the sacrifices that community members made in the war and call new generations to exhibit similar behaviour (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Message in Southern Hospital Great Hall, University of Birmingham

Notes: Birmingham University First Southern General Hospital WWI Memorial Plaque, ref no. WMO/236786.

Great War Deaths, Local Communities, and Battle Motivation in WWII

We can use the context presented by the UK in the first half of the 20th century to explore whether sacrifice in past wars has lasting effects on local communities by changing the behaviour of subsequent generations. We ask both if sacrifice in WWI had an impact on civic capital in the interwar period, and if these deaths affected the actions of the next generation of soldiers in WWII. Our hypothesis is that past acts of sacrifice and their commemoration can affect combat motivation because they foster values that encourage and normalise pro-social behaviour. That is, people raised in communities in which past generations are commemorated for their self-sacrifice will develop a set of values that emphasise collective action, and this will affect their behaviour. Building on previous work (Guiso et al. 2011), we refer to these shared prosocial values as ‘civic capital’.

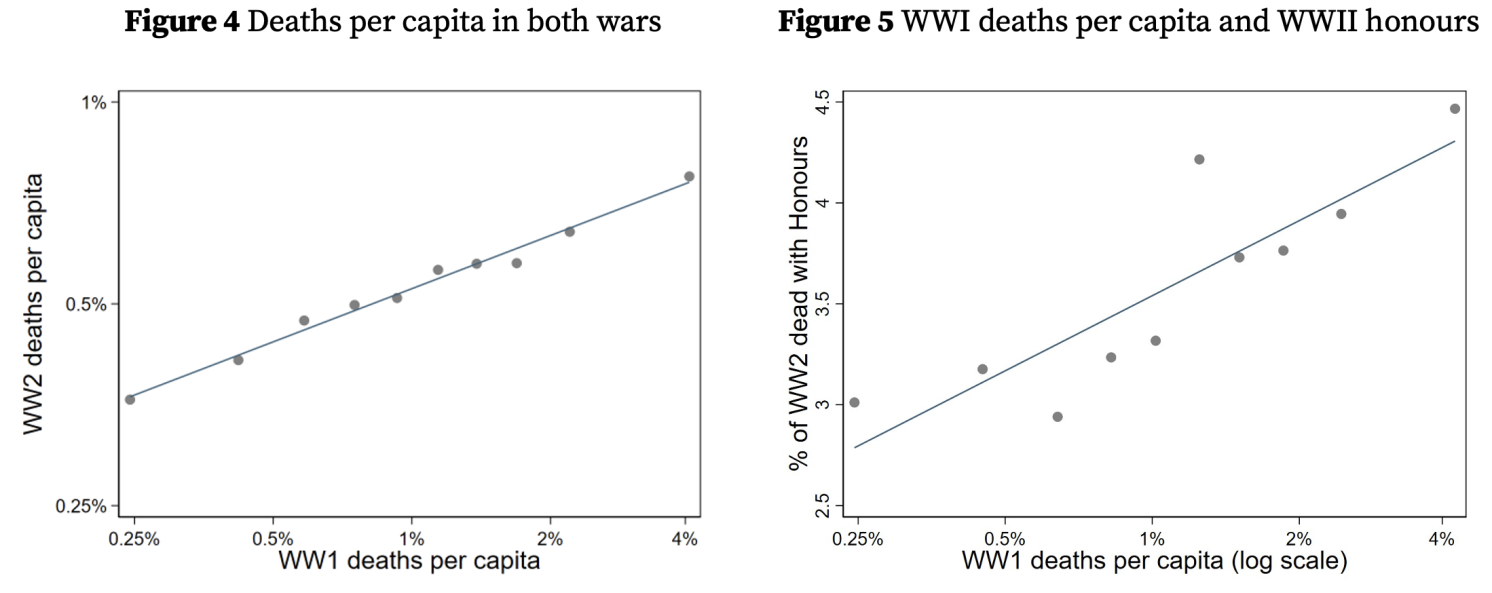

To test this hypothesis, we built a database combining information from individual-level WWI and WWII records on mobilised servicemen and deaths during the war. We geolocate these records to individual parishes of origin and use these parishes as our unit of observation in much of the analysis. For the sake of illustration, Figures 2 and 3 represent deaths per capita in WWI and WWII, respectively. We can observe that there is substantial between-parish variation in death rates in both wars. The same can be said about mobilisation rates in WWI (not shown).

The first major finding in our empirical analysis is that community-wide soldier deaths in WWI strongly predict a community’s losses in WWII, as well as the likelihood that local soldiers are awarded gallantry medals in that conflict (see Figures 4 and 5). Critically, we use a shift-share instrumental variable strategy to establish that these connections are causal and not being driven by inherent, pre-determined social and economic characteristics of communities or their residents, such as their health status, income levels, or cultural factors.

We then use different measures of civic capital at the local level to study the role played by the transmission of prosocial values in explaining the observed changes in soldier behaviour during WWI. Because measuring a community’s civic capital is characteristically difficult, we use different outcomes as proxies for this (largely unobserved) variable in the interwar period: the creation of charities, the establishment of British Legion branches, the building of high-quality memorials (as measured by Listed status), and election turnout rates. We find a positive and significant effect of WWI deaths on all of these outcomes, lending support to the notion that a community’s sacrifices during WWI led to an increase in civic capital. Using tools borrowed from the mediation literature, we show suggestive evidence indicating that it is this process of civic capital accumulation and transmission that explains the results relating WWI deaths with WWII behaviour.

All told, our results strongly indicate that deaths taking place during a war, and their remembrance by subsequent generations, can be powerful determinants of value formation and future combat motivation. Our findings have several implications. They indicate that the experience of past wars can complement other forms of public effort to increase morale, such as propaganda campaigns or public recognition of actions in service. A darker interpretation is that war begets war by increasing the resources available for future conflicts. Because cultural transmission operates – at least in part – through local networks, this also implies that the human costs of conflict can become concentrated in particular locations, even if the locations themselves are not part of the battlefield.

The extent to which the legacies of past wars still influence British communities remains an open question, and exploring the enduring effects of war deaths is an ongoing focus of our research efforts. Equally, the extent to which these results can be generalised to other contexts remains unclear. If indeed the British experience in the first half of the 20th century is somewhat representative of broader patterns, this means that current conflicts will shape the values of communities that survive those conflicts and influence the combat motivation of future generations. We hope to explore these issues in future work.

See original post for references