This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1182 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, more original reporting.

***

“If Russia does not end this war and get out of Ukraine, it will be isolated on a small island with a bunch of sub countries and the rest of us 141 countries will go forward and build a prosperous future, while Russia suffers a complete economic and technological isolation…”

-Victoria Nuland, former Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs and chief architect of NATO war against Russia, in a March 2022 interview with TASS

“I can’t preview future sanctions actions, but what I can tell you is we’re very focused on ensuring that Russia is not able to develop new projects in order to re-destine the gas that it previously sent into Europe. And I think especially because I’m talking to an audience in Europe, one of the points that’s worth emphasizing for a second is just how extremely successful Europe has been over the past two years in dramatically reorienting its energy system, de-risking its exposure to Russian oil, gas, coal supplies.”

-Assistant Secretary of State for Energy Resources Geoffrey Pyatt speaking at the 2024 Financial Times Global Commodities Summit

Things haven’t quite worked out the way Nuland, Pyatt, and company wanted them to.

Russia keeps taking everything the West throws at it and emerging stronger. Sanctions from the West continue to drive Russia to double down on its development efforts in its East and reorient its trade wholly towards Central Asia, China, India, and others.

Meanwhile, Russia has even emerged as Europe’s second largest provider of LNG, trailing only the US. Of course Europe is paying more since it’s not pipeline gas at a guaranteed rate but rather subject to fluctuations of the international LNG market, but that’s another story.

I want to focus here on what Russia is doing in its Far East. It’s a story that doesn’t involve the West aside from its futile efforts to hold back the tide and its ongoing missteps that keep making Russian trade routes more attractive to not only Moscow, but also Beijing, New Delhi, and others.

Source: Peter Fitzgerald, :commons:User:Fremantleboy, :commons:User:Local_Profil, M. Stadhaus – :Image:Russian Far East regions map.svg

The Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok held in early September offered further insight into Russia’s progress and plans. Representatives of more than 75 countries and territories took part, and 313 agreements were signed for a total of $61 billion, including investments of $43.7 billion in the Far East and the Arctic regions.

Let’s take a look at what Russia is working on and trying to attract foreign investment for despite the challenges posed by Western sanctions.

Russia and China Building Bridges

Over the past ten years, Russia has laid more than 2,000 kilometers of railway tracks and renovated more than 5,000 kilometers on the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Baikal-Amur Mainline.

Russia’s Baikal-Amur Mainline: Great Nothern Railway marks its 50th anniversary

Today one of the longest railways in the world — Russia’s Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) — is celebrating its half-century anniversary.

BAM now largely determines global logistics for the entire 21st… pic.twitter.com/E4XkXBSJWc

— Sputnik (@SputnikInt) April 23, 2024

By the end of this year, the carrying capacity of these networks is expected to reach 180 million tonnes — an increase of 36 million since 2021. More than 3,100 kilometers of tracks are planned for the next eight years, as well, which will help Moscow meet international demand for resources from its East.

China and Russia are also working together to increase the capacity of resources heading to the former. In 2022, they opened the lone vehicle bridge crossing the Amur River, which forms more than 1,600 of their roughly 4,000 border kilometers. Later that year they opened the Tongjiang Bridge, currently the only railway bridge connecting the two countries. It shortens the journey between China’s Heilongjiang region and Moscow by more than 800 kilometers over previous routes, saving 10 hours of transit time. This helped rail transport between the two countries jump to 161 million tonnes in 2023, a 36 percent increase from 2022. Over the first five months of this year, it grew another 20 percent.

A second railway bridge over the Amur is coming soon and will provide Russia’s resource-rich Sakha Republic with direct access to China. The new route will be 2,000 kilometers shorter than the current one which involves the use of sea ports. Beijing is investing in this railway construction in the Sakha Republic as part of a new international corridor in the Russian Far East: the Mohe-Magadan railway line.

Northern Sea Route

Some in Russia had been arguing for years prior to the Ukraine conflict that Russia should focus much more attention on the East as it offered more economic potential.

The US and EU full frontal assault on Russia made the decision easy — to Moscow’s benefit.

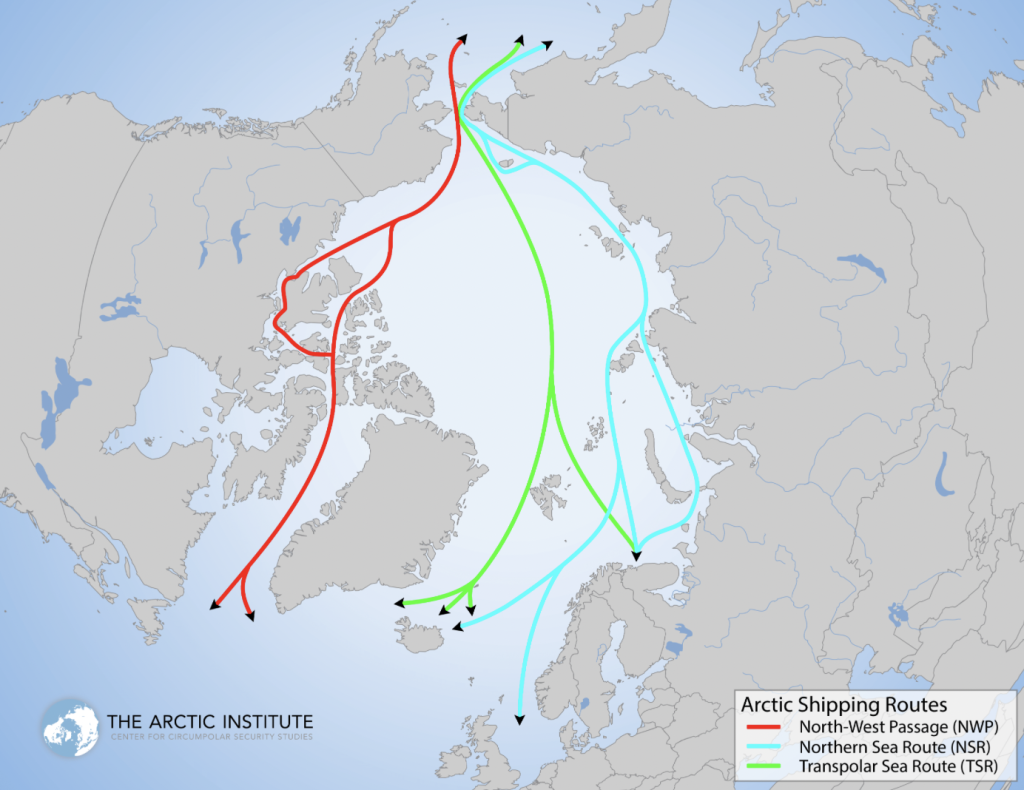

This shipping corridor passes along Russia’s northern coastline through the Arctic Ocean and is the shortest route between the western part of Eurasia and the Asia-Pacific region.

It’s bad news on the global warming front, but the route is becoming increasingly viable due to a reduction in sea ice and more and more attractive due to the US increasingly weaponizing trade and trade routes coming under fire.

The Red Sea where due to the West’s support for genocide in Gaza, Yemen’s Houthis continue to turn the Red Sea into a no-go zone for Western ships and for vessels carrying goods to and from Western markets is a fine example. It usually handles 12-15% of global trade annually, but is now mostly empty. Trouble brewing at the Caucasus crossroads due to Western meddling and Black Sea problems are other examples.

The Northern Sea Route, on the other hand, has as little geopolitical risk as one can find. It’s a 5,600-kilometer-long route controlled by one country: Russia.

It’s also home to some of the world’s richest gas and oil reserves. All of these factors have countries — especially China and India — eyeing more investment in the route and are alarming the West.

Much of Russia’s plans for the extraction and delivery of its Arctic resources previously involved the West, but that, of course, is no longer the case. European shipping companies mostly cut ties with Russian operators in 2022. As part of the economic war against Russia, Western partners abandoned Northern Sea energy projects. At first, traffic fell off a cliff, but it has since rebounded and now looks set to grow exponentially into the future with both Beijing and Moscow being the biggest winners.

The route shortens China’s shipping times with Europe by up to 50 percent compared to the Suez route, and Russia will rake in profits from transit fees.

Over the past decade, freight traffic on the Northern Sea Route increased from roughly four million tonnes in 2014 to more than 36 million last year. Moscow wants that number to continue to grow, but Washington sanctions are making it difficult.

The US is aiming to halt the development of the Russian energy sector, including a major new LNG project in the Arctic, as the quote from Pyatt referenced above shows. The threat of US sanctions for foreign participants in Russian projects has had an effect as Chinese banks, for example, are hesitant to invest in the desperately needed infrastructure upgrades to make the Northern Sea Route more viable.

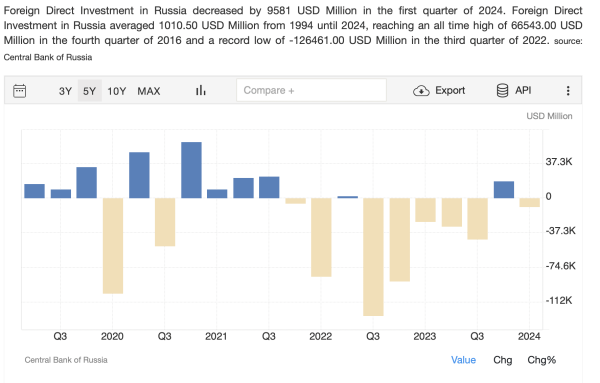

Source: Trading Economics

Yet, it’s not stopping foreign investment completely, and bit by bit China, India, and others are becoming more involved.

In June Russian state nuclear agency Rosatom signed an agreement with Chinese line Hainan Yangpu New Shipping to potentially operate a year-round route. The deal also involves collaboration in the design and construction of new ice-class container ships.

A Russian LNG tanker, Everest Energy, is currently heading East on the Northern Sea Route. The tanker is under US sanctions and is part of Russia’s shadow fleet, but what makes it special is that, according to Business Standard, it’s the first non-icebreaker carrier looking to transit the 3,500 nautical mile-long route.

In a historic first, two Chinese container ships crossed paths on the route on September 11. It might not be the last time — although Russia has a long way to go. Its Arctic region is as underpopulated as it is underdeveloped as ports, roads, and rail all need upgrades.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, speaking at the Eastern Economic Forum, confidently laid out Moscow’s plans to do just that:

We will continue to boost the freight traffic, including by developing actively Arctic deposits, rerouting cargo flows from west to east, and expanding the transit. We are building icebreakers, expanding our satellite cluster in orbit, strengthening the coastal infrastructure, and upgrading the network of emergency and rescue centres. [We have] 34 diesel icebreakers of various classes and capacity, as well as seven active nuclear icebreakers. Another four are under construction, or, to be more precise, we are already building three new nuclear icebreakers and the construction of the fourth one will start in early 2025. Seven plus four makes 11. There is also another icebreaker – a very powerful one. In fact, it is extremely powerful with, if I am not mistaken, 136,000 horsepower, if we measure its output this way. I am talking about the so-called Lider project. Its construction is already underway here in Vladivostok at Zvezda shipyard.

While foreign investment faces difficulties due to the US sanctions threat, Russian investment is soaring. From The Bell:

Prior to the war, the Russian government was banging its head against the wall trying to find a way to force businesses to stop sitting on financial reserves and prevent them paying gigantic dividends. Businesses complained that they would rather not invest because of a poor investment climate, state interference, and an unpredictable taxation policy.

Now, everything has changed. Capital investment (expenditure on new construction, higher-tech equipment for enterprises, purchase of new kit, etc.) in 2023 hit a 12-year high of 34 trillion rubles. That’s almost 10% more than the year before, according to experts.

Russia’s positive “investment gap” – i.e. the difference in growth rates between investment and GDP – has reached a 15-year high, according to the Moscow-based Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-term Forecasting (CMASF).

The biggest reason for the jump is simply that the US and Europe have forced them to. Russian companies need products, and they need to get theirs to foreign markets. That means they need new transportation and logistics infrastructure. And the list of projects goes on and on.

Russia is also modernizing the infrastructure at the Port of Korsakov, which lies on the southern part of Sakhalin Island, as part of its plans to make it a turnaround point for the Northern Sea Route. Importantly, the upgrades will mean the relocation of fish and seafood processing logistics from Busan, South Korea to the Sakhalin coast in Russia. The port will also have a large container terminal and an oil refinery.

India and Russia continue to explore more cooperation on Far East and Arctic projects.

The two sides are expediting work on the Vladivostok-Chennai Eastern Maritime Corridor on which Russia is also planning pit stops in Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia,. and linking it with the North Sea Route. Moscow and New Delhi are coordinating on a joint shipbuilding project for maritime trade as well.

At the July meeting of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Putin, they signed a Program of India-Russia cooperation in trade, economic and investment spheres in the Russian Far East for 2024 -2029, as well as cooperation principles in the Arctic. This is intended to provide the framework for a ramp up of Indian involvement in the Far East region, especially in agriculture, energy, mining, and maritime transport.

New Delhi has been receiving oil and gas at a discount, but has struggled to offer up products in return, which has hampered a transition to transactions in national currencies. According to the Financial Times, however, Russia has covertly been acquiring critical electronics from India.

Oil and Gas Projects

The sanctioned Russian LNG tanker currently heading East with an unknown destination — likely the Koryak floating storage unit located in Kamchatka or to a receiving terminal in an Asian country — is carrying gas from Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 plant. Here again, US sanctions have slowed but not stopped the project. From GIS Reports:

When Russia’s national gas giant Gazprom placed a losing bet on pipelines, Novatek invested in developing LNG and scored. China played an important supportive role already before the imposition of sanctions, assuming ownership stakes in Novatek projects. As the West sanctioned Russia’s energy interests, China has continued providing vital inputs for those projects. As late as April 2024, delivery of a 14th prefabricated plant module allowed Novatek to complete the construction of a second production unit for its Arctic LNG plant located on the Gydan Peninsula in Western Siberia, Russia. The project aims to export gas from Novatek’s Salmanovskoye and Geofizicheskoye fields, with a planned yearly capacity of 19.8 million tons across three production lines.

The same is happening with Sakhalin oil and gas projects in the Okhotsk Sea. While Exxon Mobil, which had been leading the project, exited from operation with no compensation due to western sanctions, others haven’t been so eager to bail.

Japanese companies, for example, have not withdrawn from the Sakhalin-1 and Sakhalin-2 projects, and retain their stakes in the Arctic LNG-2 project. The US is for now exempting Tokyo from its ban on providing construction and engineering services to Russian companies due to Japan’s need for Russian resources. But Tokyo could run into problems with Moscow and potentially get the boot from Sakhalin and the Arctic projects should it continue its enthusiastic support for the US, Europe, and Ukraine.

Ongoing Challenges

It’s not all smooth sailing for Moscow on the economic and development front, as laid out by its central bank at the end of August and summarized here by The Bell:

Both pessimistic scenarios (persistent inflation and high-inflation) assume that interest rates will remain in double digits. In the persistent inflation scenario, the labor market would remain tight and inflation would be driven by high domestic demand (which, in turn, would be supported by state spending), as well as increased wages. In this scenario, average interest rates would have to stay one or two percentage points higher than in the baseline. But even under such tight monetary conditions, inflation was not predicted to fall to 4-4.5% until 2026.

The high-inflation scenario is even more dire. In this eventuality, the problems in the Russian economy are amplified by a serious deterioration in external circumstances: disbalance on the financial markets leading to a global financial crisis and recession. While the Russian economy is internationally isolated, falling demand for Russian products was still assumed to cause significant damage. This scenario also envisaged more Western sanctions on Russia. If this comes to pass, the prediction is that the Russian economy would enter recession, inflation hit 13-15% and interest rates soar to 22%.

Another issue is that Russia simply needs more people to live in its Far East. Rosstat figures for 2023 show its population at a little more than 7.8 million people, which includes a small decrease in 2023. Putin, aware of the problem, spoke at the Eastern Economic Forum about Russia’s attempts to make the East more attractive:

We cannot rely on outdated logic, where new plants and factories were built first and then the authorities started thinking about their employees. This unfair logic simply does not work in a modern economy, an economy of the future that revolves around people…University campuses in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and Khabarovsk have been launched in the region, but this is clearly not enough for the Far East. I propose launching several more projects….to build new campuses in Ulan-Ude, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky and Chita…the unified subsidy mechanism, which helps fund the construction of schools and kindergartens, outpatient clinics and hospitals and sports centres, improve the urban environment and implement infrastructure modernisation projects. For example, we are building a year-round alpine skiing resort here in Primorye, as well as a national museum and theatre in Ulan-Ude. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky will receive a new community centre, and an art museum will be completed in Khabarovsk. We are building new sports facilities in Magadan and Chita.

“An economy of the future that revolves around people”? To be fair, we’re not talking about workers owning the means of production here, and some argue that Russia’s neoliberal bona fides aren’t lacking. There might be some key differences with the West, though. As Alex Krainer points out, in contrast to the UK’s current plan to cut winter fuel subsidies to 10 million pensioners in Britain, one of the first signs that Putin was going to be trouble for the West came in 2000 when he chose the Russian people over the interests of foreign capital:

During [Vladimir Putin’s] first winter as President [in 2000], entire towns and villages across the far east of the country, counting as many as 400,000 inhabitants, lost heating for the lack of coal. A serious crisis emerged with mines shutting down, workers out in the streets and even hospitals ceasing to function because of the cold. But the coal for heating was available in Russia, only most of it was already allotted for export. Vladimir Putin didn’t think that Russian people should suffer freezing conditions all winter in order for that coal to be exchanged for American dollars. He decreed that export of coal be stopped immediately and that all available quantities be sent back to Siberia to fuel the boiler stations. … in Putin’s world, well-being of the people takes precedence over financial profits of the investor class. This concept may seem exotic and alien to Westerners who for a generation had been brainwashed with neoliberal economics where profits trump any and every other concern, including health and well-being of the people. Nonetheless, I believe that beyond the brainwash, every normal person – even western-educated economists – would agree that in a crisis, the decent thing to do would be to take care of the people and let the oligarchs cope with one quarter or a year of impaired profitability of their enterprises.

***

While the latest meltdowns in the West include the US launching Russiagate Part II and the Venice Film Festival descending into chaos because of the showing of “Russians at War”, a documentary following the lives of Russian soldiers serving at the front, the rest of the world continues to move on.

Chinese automaker Chery just became the biggest foreign company in Russia after its revenue quadrupled in 2023 to more than $6.63 billion. According to Forbes Russia, 50 of the biggest foreign companies in Russia are now Chinese. That’s up from only one two years ago. The number will likely only grow as Russia and China strategically develop the former’s Far East regions. That’s because Russia has substantial reserves of virtually every commodity required to help a modern economy flourish.

Couple this with China’s manufacturing dominance, and the geniuses at the US State Department really outdid themselves by driving Beijing and Moscow together. The crazy thing is this could be the US investing and helping Russia while US plutocrats helped themselves to healthy profits. Instead they wanted it all, wanted to bring down Putin, and plunder the resources. Lo and behold, Russia and much of the rest of the world is plenty able to move on without them.