Yves here. We are posting below on an overview of the massive Pacific Palisades and environs fires. Even though there have been quite a few climate-change-related disasters, such as more frequent and extensive wildfires and more intense and locationally unexpected storms and resulting floods, the destruction of so much high value real estate might lead to even bigger shifts in insurance policy prices and even “access” to coverage.

Even though the headline speaks of a crisis, insurers may be able to roll with the current crop of disasters. They reprice their premiums annually and property and casualty insurers by reinsurance to cover exposure to large events. So they might take hits but these incidents, at least near term, should not imperil their businesses.

However, the impact on property values in high climate risk areas is another matter, particularly since real estate near beaches or in wooded areas, or even as we see now in Los Angeles, on hills (as in good views) that make them more exposed to high winds and thus catastrophic fires, has historically been prized and thus has commanded healthy prices.

The knock-on effects of scarcer and more costly home insurance will be large. Home ownership has been a, arguably the, way Americans accumulate wealth. Most buyers finance their purchases. Banks require home insurance, and in perceived-at-risk areas, also stipulate that the policies cover flood risk. Fire damage, which is a standard covered risk, will almost certainly lead home insurance to become more pricey in perceived-to-be-exposed areas. The same will be true for insurance for commercial buildings.

In the not-too-distant future, certain areas will effectively be red-lined from a flood or fire insurance perspective, either formally or by having policies be so expensive as to be unaffordable, or having terms that limit coverage in the event of wildfire or flood losses? What happens to those properties when the only market is cash-only buyers (or much smaller mortgages, limited to the maximum that insurers will cover), and then ones who understand that they are at risk of bearing the full or large losses?

And consider: what happens to current home borrowers if they can’t meet the obligations in their mortgage to maintain adequate home insurance?

This shift over the next few years means a big reset in how insurers, and following that banks, assess and price risks, with resulting reductions in value to affected properties. Business Insider looked at how this shift is under way:

- Some homes affected by the Los Angeles wildfires might not have insurance.

- Insurers have been canceling plans and declining to sign new ones in the state.

- Years of worsening wildfires have increased payouts and other costs for insurers in California.

…..State Farm, for instance, said in 2023 that it would no longer accept new homeowners’ insurance applications in California. Then, last year, the company said it would end coverage for 72,000 homes and apartments in the state. Both announcements cited risks from catastrophes as one of the reasons for the decisions.

Homes in the upscale Pacific Palisades neighborhood, one of the areas hardest hit by the fires so far, were among those affected when State Farm canceled the policies last year, the Los Angeles Times reported in April

The article later describes how the state insurer nevertheless plans to force insurers to offer coverage. Good luck with that:

A new rule, set to take effect about a month into 2025, will require home insurers to offer coverage in areas at high risk of fire, the Associated Press reported in December. Ricardo Lara, California’s insurance commissioner, announced the rule just days before the Los Angeles fires broke out.

Obviously, insurers can largely vitiate that requirement via high prices, particularly for new policy applicants. And in the light of the ginormous Los Angles fire, they can contend the pricing is risk-justified.

Changes on the insurance front are still very much in play, but California’s ABC7 gives a flavor of what is in the offing:

Part of the governor’s state of emergency includes an insurance non-renewal moratorium. The state’s insurance commissioner told our colleagues at KABC Wednesday that he’s working on protecting homeowners in the affected areas from being dropped by their insurer for one year.

It’s raising serious questions about how these fires will influence California’s growing insurance crisis.

As we watch the devastating wildfires move through Los Angeles County, it’s posing new threats to the state’s growing insurance crisis. With more than 13,000 homes at risk, losses could approach at least $10 billion, according to preliminary estimates from JP Morgan Chase. This paired with concerns as the state is implementing a new reform plan that analysts say could raise insurance premiums by 40% on average. In fire-prone areas, the increases could be up to 100% or more…

The commissioner’s plan is implementing what is called “catastrophe modeling,” which uses software algorithms to assess risk and make decisions on your coverage. So anything from having a fire in your area, to poor mitigation, to lack of staffing at your local fire department — they could all impact your ability to have coverage. It’s an issue we’re seeing in Pacific Palisades… and right here at home.

The city of Oakland just announced they are going to close five fire stations because of their budget crisis, one of the many factors insurance companies consider in the data that they access.

Needless to say, this is not reassuring.

Now to the main event. Lambert will have some more updates in Links, but a quick look at one aggregator says things are getting worse, with fires in Hollywood Hill and Laurel Canyon and Sunset Boulevard closed.

By Bob Henson. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Prolonged, top-end bout of damaging winds will hit parts of Southern California from Tuesday to Thursday, January 6-8. The winds themselves could bring serious havoc, knocking down trees, limbs, and power lines. An even bigger worry is fire: the fierce gusts will scrub a landscape parched by one of the driest starts to the water year in Southern California history, so any wildfire that gains traction could be devastating. Update (11:30 p.m. EST Tuesday): The situation in northern parts of the sprawling Los Angeles area was rapidly deteriorating tonight, as the Palisades Fire and Close Fire were growing rapidly and moving southward toward heavily populated neighborhoods that rarely see a high-end fire threat. More than 30,000 people were being evacuated, including across large parts of Santa Monica and Pasadena.

As of midday Tuesday, gusts of 84 mph had already been recorded on Magic Mountain, just north of the San Fernando Valley, and 50 to 70 mph gusts were already becoming widespread. A fast-moving fire had erupted by late morning above Pacific Palisades, quickly growing to 200 acres before noon PST.

Strong winds in Pasadena pushing 60 MPH, with gusts in the hills to 80 MPH. @NWSLosAngeles pic.twitter.com/f9d6VCi9qD

— Edgar McGregor (@edgarrmcgregor) January 7, 2025

The worst is likely to play out late Tuesday and on Wednesday when parts of Ventura and northern Los Angeles counties can expect “extremely critical” fire weather, the highest possible category in outlooks issued by the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center.

Communities at the greatest fire-weather risk lie along the north side of the San Fernando Valley and into the adjacent higher terrain, including Santa Clarita, Simi Valley, Moorpark, San Fernando, and La Canada Flintridge.

Critical fire-weather conditions (just one step down from “extremely critical”) will extend over a much broader area, possibly affecting millions of people from the greater Los Angeles to San Diego regions and into the Inland Empire. Widespread wind gusts in the 50 to 80 mph range will extend all the way to the coast in some areas, especially north of Los Angeles, and gusts could range as high as 100 mph in the mountains and foothills.

“Given the intensity of the winds, extreme fire behavior appears likely should ignitions occur,” warned the Storm Prediction Center in an outlook issued early Tuesday.

Strong winds are coming. This is a Particularly Dangerous Situation – in other words, this is about as bad as it gets in terms of fire weather. Stay aware of your surroundings. Be ready to evacuate, especially if in a high fire risk area. Be careful with fire sources. #cawx pic.twitter.com/476t5Q3uOw

— NWS Los Angeles (@NWSLosAngeles) January 7, 2025

The preconditions for a January fire in Southern California couldn’t be much worse. After two years of generous moisture (especially in 2022-23), the state’s 2024-25 wet season has gotten off to an intensely bifurcated start: unusually wet in NoCal and near-record dry in SoCal. We’re now in weak to marginal La Niña conditions, and La Niña is typically wetter to the north and drier to the south along the U.S. West Coast, but the stark contrast this winter is especially striking. Two cases in point, looking at rainfall from October through December 2024:

- Eureka, CA: 23.18 inches (12th wettest in 139 years of data; average 15.27 inches for 1991-2020)

- San Diego, CA: 0.14 inches (3rd driest in 175 years of data; average for 1991-2020 was 2.96 inches)

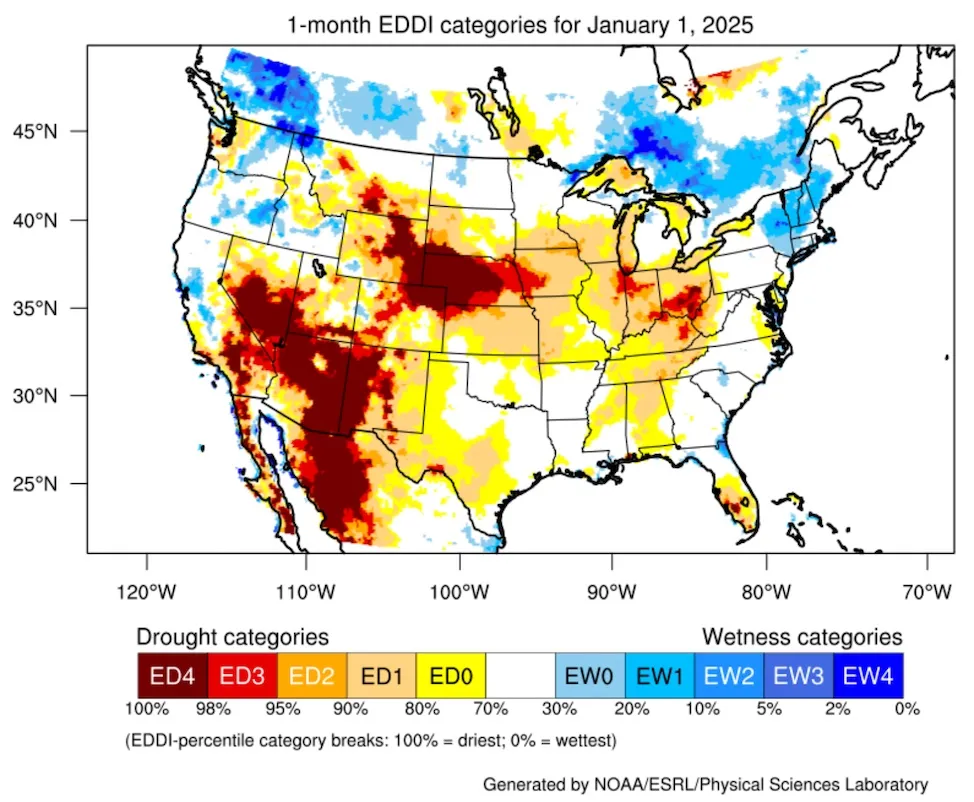

Southern California had not yet pushed into severe to exceptional drought as of December 31, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. But the landscape has been drying out quickly, as reflected in Fig. 1 below of the Evaporative Demand Drought Index (a measure of how “thirsty” the atmosphere has been over a given time frame).

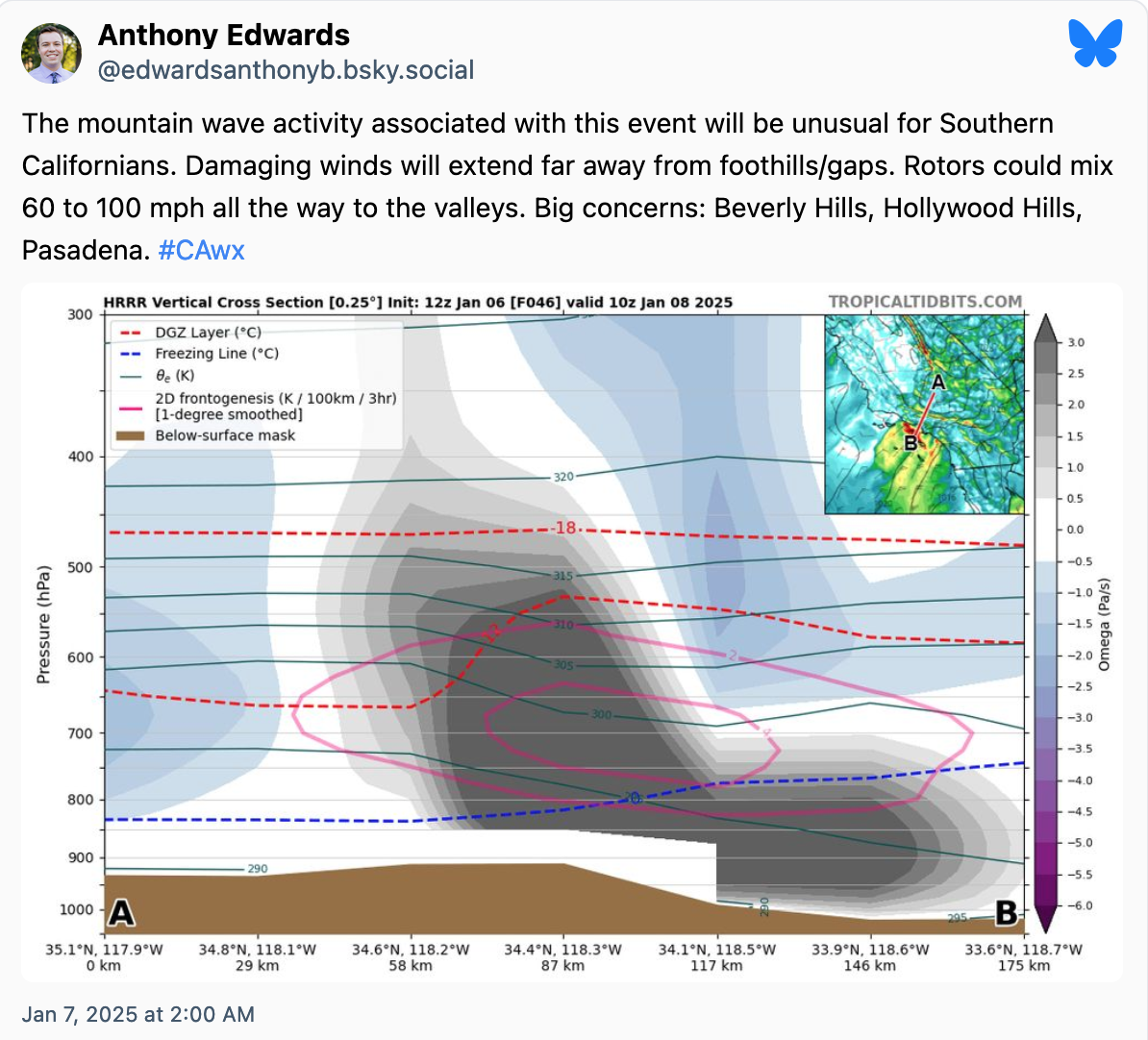

On top of the unusually dry conditions for early January, we’re now in the heart of the Santa Ana wind season. These notorious and dangerous downslope winds, which occur when higher-level winds are forced over the coastal mountains and toward the coast, typically plague coastal Southern California a few times each year. This week’s peak winds may arrive more from the north versus the northeast, compared to a classic Santa Ana event, and the associated wind-bearing mountain waves (which are shaped by the vertical temperature profile at mountaintop level) could punch further toward the coast than usual.

The National Weather Service warned that this could be the strongest Santa Ana wind event in Southern California in over 13 years, since Dec. 1 2011, when Whitaker Peak (elev. 4120’) in Los Angeles County recorded a gust of 97 mph (156 km/h). The winds toppled thousands of trees, and over 200,000 homes lost electricity, mostly in the San Gabriel Valley towns of Altadena and Pasadena

There’s no research indicating that downslope winds like this are becoming more intense or frequent with human-caused climate change, or that we should expect them to. But it’s abundantly clear that fire season is lengthening in Southern California, as documented in this 2021 study by California weather expert and climate researcher Daniel Swain, and it’s likely to continue stretching out (see this 2022 study). These shifts will open the door for summer-dried vegetation to stay parched and highly flammable until the winter rains arrive (even if that’s after New Year’s Day).

Although this week’s setup isn’t unusually warm, higher temperatures overall are making droughts more dangerous by allowing more water to evaporate from landscapes and reservoirs.

Clarity Corner: The Problem with “Hurricane-Force Wind Gusts”

There have already been media references to this week’s Southern California winds possibly delivering “hurricane-force wind gusts.” This term can be misleading, though. Hurricanes are defined as tropical cyclones with sustainedwinds of at least 74 mph (65 knots or 119 km/hr). But the peak wind gusts in a given hurricane are typically 20 to 30 percent higher than the top sustained wind. So a minimal hurricane with 75 mph sustained winds can be expected to produce peak gusts in the range of 90 to 100 mph.

Where this gets tricky is that wind gusts of 75 mph or more are sometimes referred to as “hurricane-force.” But it doesn’t take a hurricane to produce such gusts. Even a tropical storm with top sustained winds of only 60 mph can do the trick. Moreover, the winds in a mountain-related downslope windstorm are typically far more variable than in a hurricane, sometimes even going from near-calm to peak strength in a matter of a few minutes. So keep in mind that a Santa Ana windstorm with peak gusts of, say, 80 mph – while still fearsome and highly dangerous – wouldn’t pack the same wind punch as a Category 1 hurricane.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.