BBC

BBC“I saw five people smiling, looking forward to their journey.”

That was Renata Rojas’ recollection of her time on a support ship with five people bound for the Titanic wreck. They were about to climb into a submersible made by Oceangate.

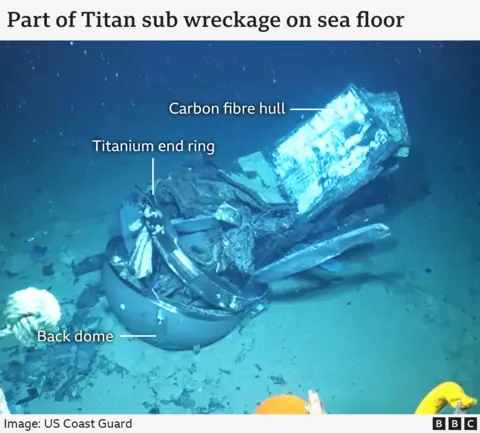

Just 90 minutes later, these five would become the victims of a deep sea disaster: an implosion. Images from the depths of the Atlantic show the wreckage of the sub crushed, mangled, and scattered across the sea floor.

The photos were released by the US Coast Guard during an inquiry to establish what led to its catastrophic failure in June 2023.

The inquiry finished on Friday and over the past two weeks of hearings, a picture has emerged of ignored safety warnings and a history of technical problems. We have also gained new insight into the final hours of those on board.

It has shown us that this story won’t go away any time soon.

Passengers unaware of impending disaster

British explorer Hamish Harding and British-Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood, who’d brought his 19-year-old son Suleman along, had paid Oceangate for a dive to see the Titanic which lies 3,800m down.

The sub was piloted by the company’s CEO Stockton Rush with French Titanic expert Paul-Henri Nargeolet as co-pilot.

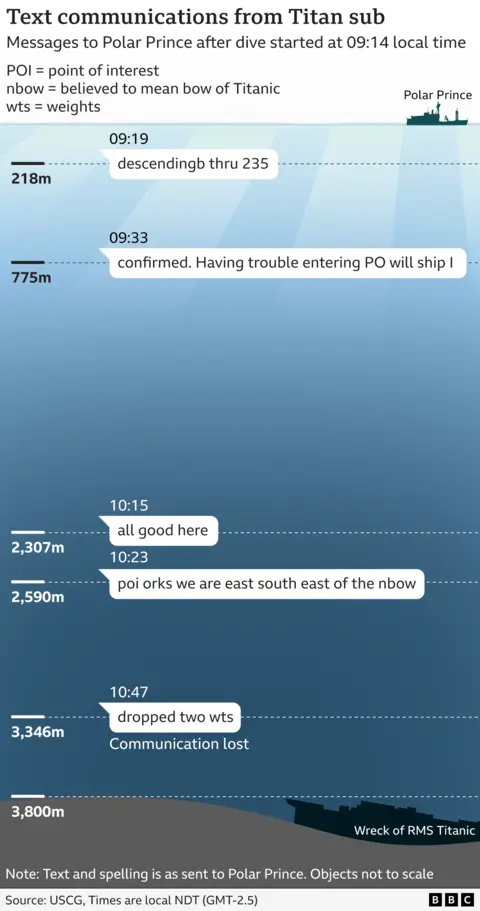

Once the craft had slipped beneath the waves, it could send short text messages to the surface. A message sent from about 2,300m said “All good here”.

Supplied via Reuters / AFP

Supplied via Reuters / AFPAbout an hour and a half into the dive, from 3,346m, Titan’s final message reported it had released two weights to slow its descent as it neared the sea floor.

Communications were then lost – the sub had imploded.

The US Coast Guard said nothing in the messages that indicated that the passengers knew their craft was failing.

The implosion was instantaneous. There would have been no time to even register what was happening.

Unorthodox sub was flawed from the start

Mr Rush proudly described the Titan as “experimental”. But others had voiced their concerns to him about its unconventional design in the years prior to the dive.

At the hearing David Lochridge, Oceangate’s former director of marine operations, described Titan as an “abomination”.

In 2018, he’d compiled a report highlighting multiple safety issues, but said these concerns were dismissed and he was fired.

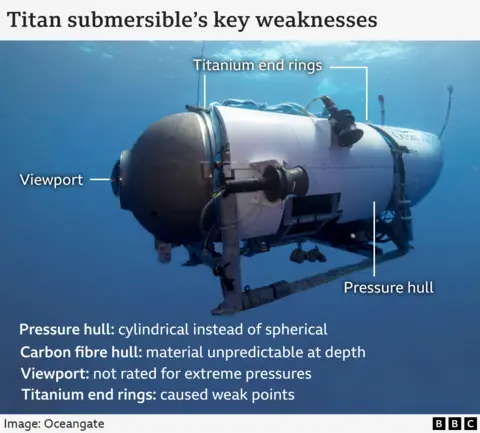

Titan had several unusual features.

The shape of its hull – the part where the passengers were – was cylindrical rather than spherical so the effects of the pressure were not distributed evenly.

A window was installed but only considered safe down to 1,300m. The US Coast Guard also heard about problems with the joins between different parts of the sub.

The hull’s material attracted the most attention – it was made from layers of carbon fibre mixed with resin.

US Coastguard

US CoastguardRoy Thomas from the American Bureau of Shipping said carbon fibre was not approved for deep sea subs because it can weaken with every dive and fail suddenly without warning.

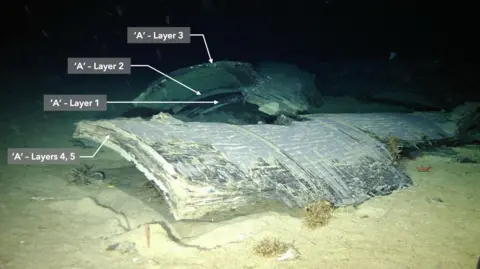

The National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) presented an analysis of samples of Titan’s hull left over from its construction.

It showed areas where the carbon fibre layers had separated – a known problem called delamination – as well as wrinkles, waviness and voids within its structure.

This suggests the material contained imperfections before the sub had even made a dive.

The NTSB team also saw this delamination in wreckage found on the seafloor.

Most of the hull was destroyed, but in the pieces that survived, the carbon fibre has split into layers and in some places had cracked.

Officials are not currently saying the hull’s failure caused the implosion, but it’s a key focus of the investigation.

Loud bang – a missed warning sign

A place on the sub cost up to $250,000 (£186,000) – and over the course of 2021 and 2022 Titan made 23 dives, 12 of which successfully reached the wreck of the Titanic.

But these descents were far from problem free. A dive log book recorded 118 technical faults, ranging from thrusters failing, to batteries dying – and once the front dome of the sub fell off.

The investigation focused on a dive that took place in 2022, when paying passenger Fred Hagen heard an “alarming” noise as the sub was returning to the surface.

“We were still underwater and there was a large bang or cracking sound,” he said.

“We were all concerned that maybe there was a crack in the hull.”

He said Mr Rush thought the noise was the sub shifting in the metal frame that surrounded it.

The US Coast Guard inquiry was shown new analysis of data from the sub’s sensors, suggesting the noise was caused by a change in the fabric of the hull.

This affected how Titan was able to respond to the pressures of the deep.

Phil Brooks, Oceangate’s former Engineering Director, said the craft wasn’t properly checked after that dive because the company was struggling financially, and instead it was left for months on the dockside in Canada.

Boss was convinced his sub was safe

“I’m not dying. No-one is dying on my watch – period.”

These were the words of Mr Rush in a 2018 transcript of a meeting at Oceangate HQ.

When questioned about Titan’s safety, he replied: “I understand this kind of risk, and I’m going into it with eyes open and I think this is one of the safest things I will ever do.”

According to some witnesses Mr Rush had an unwavering belief in his sub. They described a dominating personality who wouldn’t tolerate dissenting views.

“Stockton would fight for what he wanted… and he wouldn’t give an inch much at all,” said Tony Nissen, a former engineering director.

“Most people would just eventually back down from Stockton.”

Passenger Fred Hagen disagreed, describing Mr Rush as a “brilliant man”.

“Stockton made a very conscious and astute effort to maintain a perceptible culture of safety around a high risk environment.”

US authorities knew of safety concerns

Former employee David Lochridge was so worried about Titan that he went to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

This is the US government body that sets and enforces workplace safety standards.

Correspondence reveals that he provided extensive information about the sub’s problems – and was placed on OSHA’s whistleblower witness protection scheme.

But he said OSHA were slow and failed to act, and after increasing pressure from Oceangate’s lawyers, he dropped the case and signed a non disclosure agreement.

He told the hearing: “I believe that if OSHA had attempted to investigate the seriousness of the concerns I raised on multiple occasions this tragedy may have been prevented.”

Sub safety rules need to change

Deep-sea subs can undergo an extensive safety assessment by independent marine organisations such as the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) or DNV (a global accreditation organisation based in Norway).

Almost all operators complete this certification process, but Oceangate chose not to for Titan. At the hearing, some industry experts called for it to become compulsory.

“I think as long as we insist on certification as a requirement for continued human occupied exploration in the deep sea we can avoid these kinds of tragic outcomes,” said Patrick Lahey, CEO of Triton submarines.

Story isn’t over yet

Witnesses at the hearing included former Oceangate employees, paying passengers who’d made dives in the sub, industry experts and those involved in the search and rescue effort.

But some key people were noticeably missing.

Mr Rush’s wife Wendy, who was Oceangate’s communications director and played a central role in the company, did not appear. Nor did director of operations and sub pilot Scott Griffith or former US Coast Guard Rear Admiral John Lockwood, who was on Oceangate’s board.

The reasons for their absences were not given and their version of events remain unheard.

The US Coast Guard will now put together a final report with the aim of preventing a disaster like this from ever happening again.

But the story will not end there.

Criminal prosecutions may follow. And private lawsuits too – the family of French diver PH Nargeolet is already suing for more than $50 million.

The ripples from this deep sea tragedy are likely to continue for many years.