By KLG, who has held research and academic positions in three US medical schools since 1995 and is currently Professor of Biochemistry and Associate Dean. He has performed and directed research on protein structure, function, and evolution; cell adhesion and motility; the mechanism of viral fusion proteins; and assembly of the vertebrate heart. He has served on national review panels of both public and private funding agencies, and his research and that of his students has been funded by the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and National Institutes of Health.

During the recent hundredth “anniversary” of the European conflagration that began in 1914, I read several books to refresh my knowledge of The Great War, which later became known as World War I for horrible but sufficient reason. The first was The Guns of August by Barbara Tuchman (1963). I had first read Tuchman as a college freshman and had forgotten how vivid she can be. I then read The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2014 pb) by Christopher Clark and followed that with To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918 by Adam Hochschild (2012). The Sleepwalkers illustrated, among other things, how rank stupidity, all too human cupidity, and imperial madness can lead nations and classes [1] into the abyss without ever stopping to ask, “What comes next?”. To End All Wars is necessary to understand how the quintessential Liberal nation can go so far off the rails that they jail their most recognized philosopher, in the person of Bertrand Russell. The nation that styles itself a “beacon of democracy for the world” is currently certifiable when it comes to the outright denial of its erstwhile values. Will someone please tell the shade of Ben Franklin that, no, we could not keep it.

Later I skimmed my copy of The Doughboys (1963) by Laurence Stallings. The Doughboys has been a special book to me because of my Great Uncle Tom (1890-1972), who was an older Doughboy in 1917. Although he would not talk much about the Great War when I visited him as a young boy on his small farm in the late-1960s, my Great Aunt Marie would, however, tell of her worries about the fighting “over there” where her Tom was a private in “General Pershing’s American Expeditionary Forces.” [2]

What my study of the horrific history of The Great War taught me for all time is that “War is never the answer to a properly posed question.” No exceptions, no appeal. And I have for the past ten years essentially been a pacifist. As one who missed “my war” by one year – when I turned 18, the Selective Service System was taking only 19-year-olds in the Draft – I have always looked askance at those claiming it is the answer to anything. The War in Vietnam never made sense to me as I watched it unfold at 6:30 pm almost every evening on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite through my graduation from high school. Clausewitz was correct, despite varying interpretations: War is nothing but (mistaken) politics by other, explicitly lethal and thoroughly destructive, means. The politicians who make war never have to fight it. And then there is Major General Smedley Butler with his compelling description of war as a racket.

Since October of last year, I have reprised my Great War reading by selecting several books on the historical background of just one of our current wars during the present era that seems likely to be remembered as “The Era of All War, All the Time.” I cannot remember when the United States has not been at war somewhere on planet Earth. With more than 700 known military outposts circling the globe, it is difficult to see how this finally ends in anything other than catastrophe.

This current war is certainly the most fraught, in real time, in our history. Most other wars have been considered a “Good War,” at least early in their prosecution. Nevertheless, we must make the effort to understand this as best we can. I chose to read several books about Palestine, including a few polemics, although just as “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter,” one person’s standard history may be nothing but a polemic to another. Four of these books, in the non-polemical category, will be discussed briefly here:

Enemies and Neighbors: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017 (Allen Lane, 2017; Penguin pb 2018) by Ian Black, who was Middle East editor of the Guardian until 2016 and served for 35 years as the paper’s Jerusalem Correspondent, Diplomatic Editor, and Chief Foreign Editorial Writer. Twenty-six chapters comprise the book, covering Palestine from 1882 until 2017, including the beginnings of the Zionist movement through the hundredth anniversary of the Balfour Declaration and President Donald Trump’s promise, fulfilled in 2018, to move the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonial Conquest and Resistance (Profile Books, 2020) by Rashid Khalidi, the Edward Said Professor of Palestinian Studies at Columbia University, is the second. His story of six declarations of war on Palestine (1917-1939, 1947-1948, 1967, 1982, 1987-1995, 2000-2014) generally follows the timeline of Enemies and Neighbors. I imagine a new edition will include the seventh declaration of war. The history of Palestine over the past hundred years is intertwined with that of his family, who were leaders of Palestinian society and politics until 1948. The book includes a photograph of the ruin of the family house. Family history and archives are a source of much of his material.

Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine before the Nakba (2016, in Spanish by Ediciones del Oriente y el Mediterráneo, Madrid; Republished in 2024 by Haymarket Books, translated into English) by Teresa Aranguren and Sandra Barrilaro. This collection includes rescued photographs of a vibrant life in Palestine that included Arabs, Christians, and Jews who lived on the land that politicians and adherents of the three Abrahamic religions and cartographers called Palestine, then and now.

Khirbet Khizeh: A Novel (Originally published in Hebrew in 1949; 2008 in English translation by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux; also known as Hirbet Hizeh and Hirbet Hizah) by S. Yizhar (1916-2006) who was Yizhar Smilansky. Y. Smilansky was born in Rehovot and was a member of the Knesset from 1949-1966. He previously served as an intelligence officer during the 1948 – 1949 war that led to establishment and recognition of the State of Israel. Khirbet Khizeh is a short historical novel (109 pages) about the expulsion of the Arabs from the fictional village of that name.

Each of these has been reviewed before. There is no reason to repeat those here. Instead, I will proceed here by letting many of the protagonists speak for themselves. And speak with a clear voice they do, addressing their world in terms that resonate today.

To begin with Enemies and Neighbors, this book is long (455 pages), complete, fair, and eminently readable, actually something of a page turner. The history and motivations of all sides are considered with sensitivity and historical sophistication. The primary sources are clearly identified in this work of history, journalism, and interpretation by someone with long experience in Palestine. It is authoritative and accessible.

Enemies and Neighbors, Chapter 3: 1917-1929, p. 62. The writer quoted in the following excerpt is the historian of nationalism Hans Kohn, who described the Zionist-Arab confrontation against the wider background of colonialism elsewhere. As an extension of the imperatives of every empire, it should be remembered that the British Empire, upon which the sun never set at the time, was nothing if not violent according to the recent work by Caroline Elkins. Empire is always violent, whether the fact of empire or its inherent violence are acknowledged by the colonialists:

Frequently the most reactionary imperialist press in England and France portrays the national movements in India, Egypt, and China in a similar fashion…whenever the national movements of oppressed peoples threaten the interest of the colonial power…We pretend to be innocent victims…Of course the Arabs attacked us in August. Since they have no armies they could not obey the rules of war. They perpetrated the barbaric acts of a colonial revolt. But we are obliged to look deeper into the cause of this revolt. We have been in Palestine for twelve years…without having even once made a serious attempt at seeking through negotiations the consent of the indigenous people. We have been relying exclusively upon Great Britain’s military might. We have set ourselves goals which by their very nature had to lead to conflict with the Arabs…We ought to have recognized that these…would be…the just cause of a national uprising against us…We pretended the Arabs did not exist.

Enemies and Neighbors, Chapter 6: 1939-1945, p. 100. In 1940, Yosef Weitz of the Jewish National Fund confided to his diary – in a subsequently much quoted statement – that:

(T)here is no room for both people together in this country. The only solution is a Palestine…without Arabs. And there is no other way than to transfer all of them. There is no other way.

Transfer them where? As noted by Ian Black, this was not an operational plan in 1940, but it was not forgotten. It is difficult to view policy of the current State of Israel as much different 84 years later. It is also impossible to see this as anything other than a bold statement of the colonial mind. Certainly, the colonization of North America proceeded with much the same justification. The British Empire was better at accommodating themselves to their colonial possessions, but no less violent all the same in the view of the colonized.

Enemies and Neighbors, Chapter 7: 1945-1949, p. 124. Palestinian scholar Bayan Nuwayhid al-Hout:

While the Jewish forces fought, dreaming of their state, the Arab leaders ordered their armies to fight a limited war, dreaming of and praying for a ceasefire.

Both Ian Black and Rashid Khalidi discuss the misapprehensions and wishful thinking, along with double dealing, of Palestinian politicians and leaders. This is illustrated here in one simple passage. Political fecklessness has been a constant in Palestine, and such behavior was often characteristic of each side (Palestinians, Israelis, Syrians, Jordanians, Egyptians) of this ongoing crisis, but the Zionists and Israelis were certainly more persistent and perspicacious in diplomacy, politics, and economics. The colonizer always has these advantages.

Enemies and Neighbors, Chapter 7: 1953-1958. The following is a very clear statement from Moshe Dayan, an officer in the IDF and Israeli politician who is still remembered well, after the horrific murder of Roy Rotberg from Kibbutz Nahal Oz on the border with Gaza. This is particularly relevant today:

Let us not blame the murderers today. Why should we complain about their burning hatred for us? For eight years they have been sitting in the refugee camps in Gaza, watching us transforming their lands and the villages where they and their fathers dwelt, into our property…(still)…We have no choice but to fight. This is our life’s choice, to be prepared and armed, strong and determined, lest the sword be stricken from our fist and our lives cut down. We are a generation that settles the land, and without the steel helmet and the cannon’s fire we will not be able to plant a tree and build a home. Let us not be deterred from seeing the loathing that is inflaming and filling the lives of the hundreds of thousands of Arabs who live around us. Let us not avert our eyes lest our arms weaken.

As noted in Enemies and Neighbors, this has been aptly described as an Israeli version of the American doctrine of Manifest Destiny, the ostensibly moral, economic, military, and political justification for the colonial expropriation of North America and beyond, with predictable and inevitable consequences for indigenous peoples who found themselves in the way.

Enemies and Neighbors, Chapter 13: 1968-1972, p. 224. After the dazzling military success that was the Six-Day War of June 1967, the general awareness of Palestinians by Israelis was reflected by Labour Prime Minister Golda Meir in her statement from 1969:

‘There was no such thing as Palestinians…It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine considering itself as a Palestinian people we came and threw them out and took their country from them. They did not exist.’ (One can only suppose this was news to the Moshe Dayan of 1956)…Meir was nothing if not consistent: she insisted there could be no return to the pre-1967 borders, but brushed aside concerns about the annexation of parts of the West Bank. ‘Israel wants only a minimum of Arab population in the Jordanianterritory it wishes to keep.’ (italics in the original)

This was said during the rightfully “angry anti-Palestinian mood after the Munich Olympics killings.” But it had precedent going back the beginnings of the Zionist movement.

Enemies and Neighbors, Chapter 7: 1945-1949, p. 224, p 121. There was and is a Palestine with a Palestinian people. The numbers vary, but the consensus is that more than 700,000 Palestinians lived in Palestine in 1948. Many still do, but many left, not fully understanding that return would be impossible. From Shafiq al-Hout, then a sixteen-year-old crowded on the deck of a Greek ship bound for Beirut:

I remember watching Jaffa disappear from sight until there was nothing but water all around…It never occurred to me that I would never see it again.

The remainder of Enemies and Neighbors recounts the history of Israel and Palestine up to 2017. Since 1967, the alternating responses of violence-for-violence, outrage-for-outrage, atrocity-for-atrocity – the list is long and makes for dreary reading – have only led us further into a cul de sac from which there may be no retreat.

The Hundred Years’ War by Rashid Khalidi is an affecting, heartfelt, and clear-eyed history of the same period covered in Enemies and Neighbors. This is a near “first person” account through his family’s experience in Palestine, beginning with the Balfour Declaration, in which (p. 34):

(T)he Jewish people, and only the Jewish people, are described as having a historic connection to Palestine. In the eyes of the drafters, the entire two-thousand-year-old built environment of the country with its villages, shrines, castles, and monuments dating to the Ottoman, Mameluke, Ayyubid, Crusader, Abbasid, Umayyad, Byzantine, and earlier periods belonged to no people at all, or only to amorphous religious groups. There were people there, certainly, but they had no history or collective existence, and could therefore be ignored. The roots of what the Israeli sociologist Baruch Kimmerling called the politicide of the Palestinian people are on full display in the Mandate’s preamble. The surest way to eradicate a people’s right to their land is to deny their historical connection to it.

The second surest way to do so is to condemn the indigenous people for failing to “develop” the land as they should in the eyes of those who covet it. This has been a justification, going back to John Locke, for the dispossession of indigenous peoples in the way of “progress.” It has been used in every colonial project. Whatever one thinks of The Hundred Years’ War, Rashid Khalidi clearly makes the case that a people have the right to tell their own history on their own terms. This, of course, also applies to the Zionist foundations of the State of Israel. The basic understanding of which can be found, perhaps, as part of American political and popular culture here and in this version of its stirring song (3:15), which I sang uncomprehendingly as a member of the Eighth Grade Chorus not too long after the Six-Day War. I came to understand the argument better when Menachem Begin prevailed in Israeli politics in the late-1970s and spoke often of the State of Israel’s God-given right to possession of Judea and Samaria.

Whatever Golda Meir meant when she said “There was no such thing as Palestinians…It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine considering itself as a Palestinian people we came and threw them out and took their country from them. They did not exist,” Against Erasure makes the opposite case very well. This book is a remarkable documentary text, not unlike this most valuable treasure (7:57 video worth the time) that illustrates what can only be viewed as the exceedingly rich, and in ways too many to count, complementary culture that existed contemporaneously 2500 miles to the north and east or Palestine. The following selected photographs speak for the people of a settled pastoral, agricultural, and commercial culture that thrived in Palestine before 1948.

(1) Citrus fruits and olives were two major crops cultivated in Palestine before and during the Mandate. Olives still are and Palestinian olive oil can be found here, when it is available. Highly recommended.’

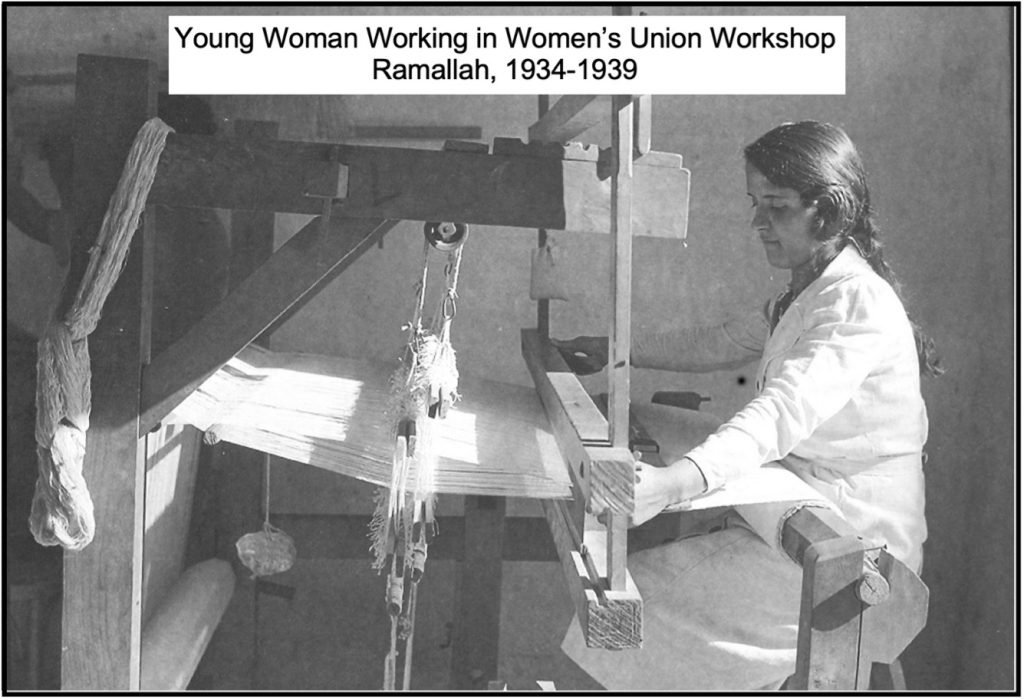

(2) What we would now call “artisanal” textiles were produced for use and for trade.

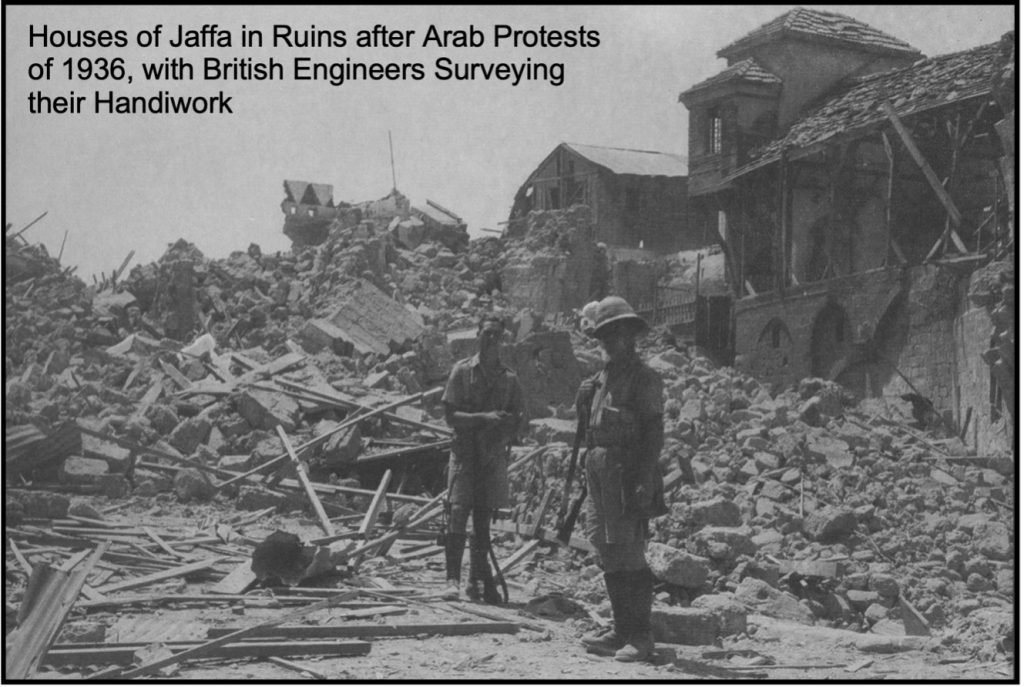

(3) Some history repeats itself with more than rhyme.

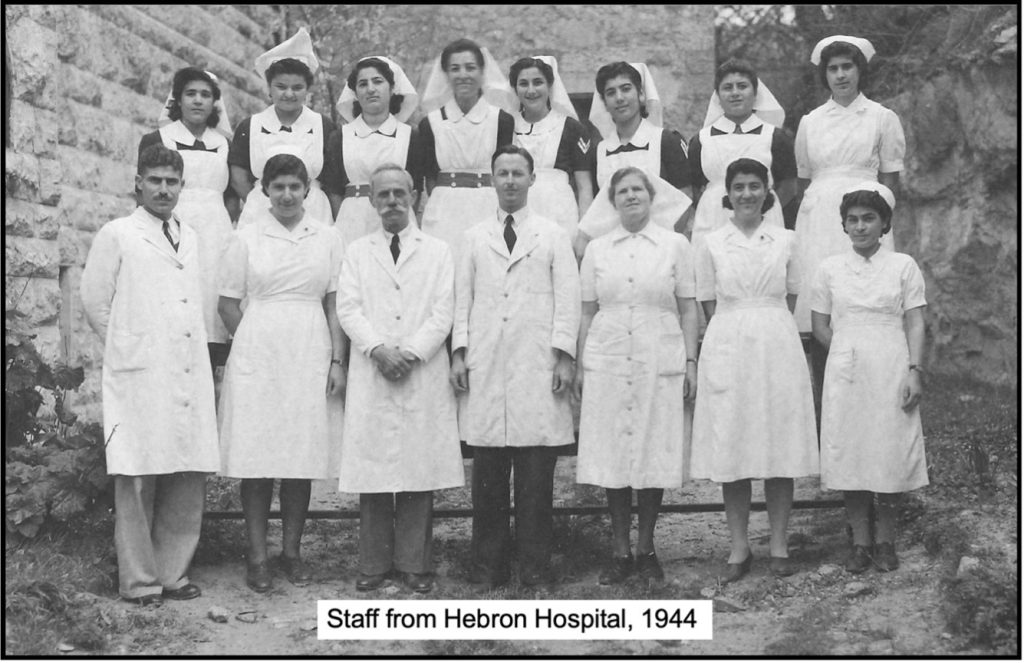

(4) A Dr. Walker, nationality unknown, probably in the center of the front row, ran the Hebron hospital.

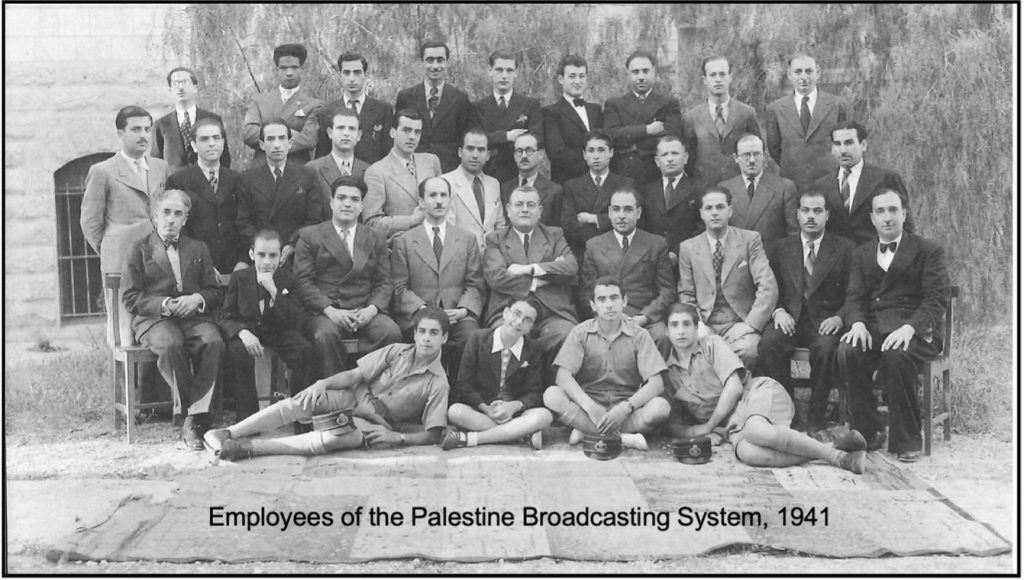

(5) The Palestine Broadcasting Service was active from 1936 until it was shut down in 1948.

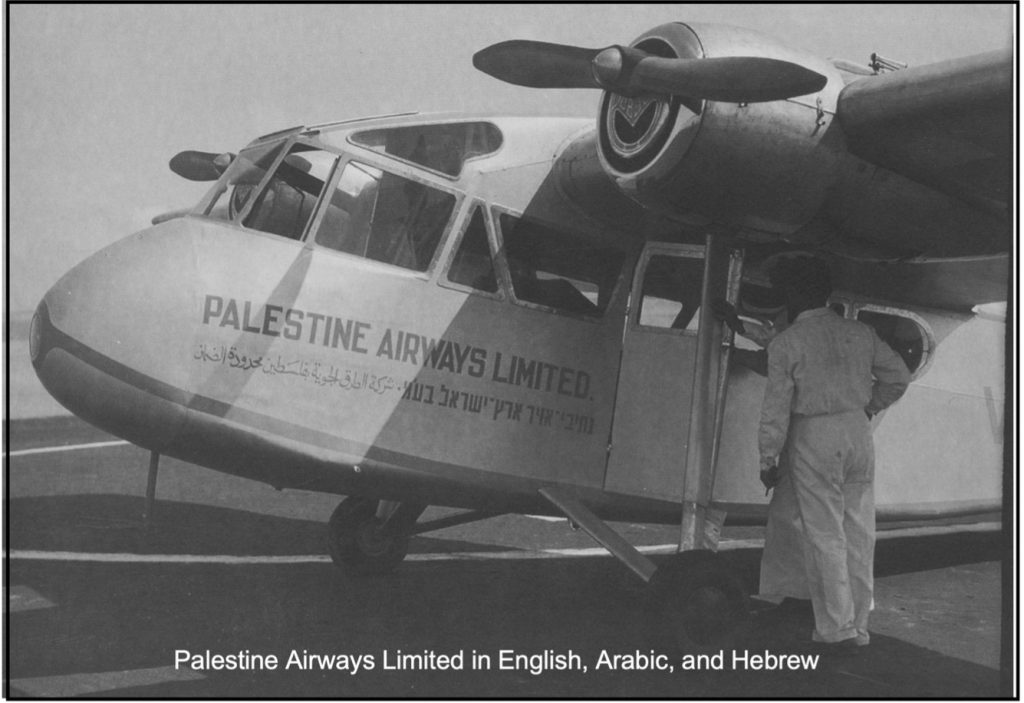

(6) Note the name of the company is presented in the three languages of one Palestine.

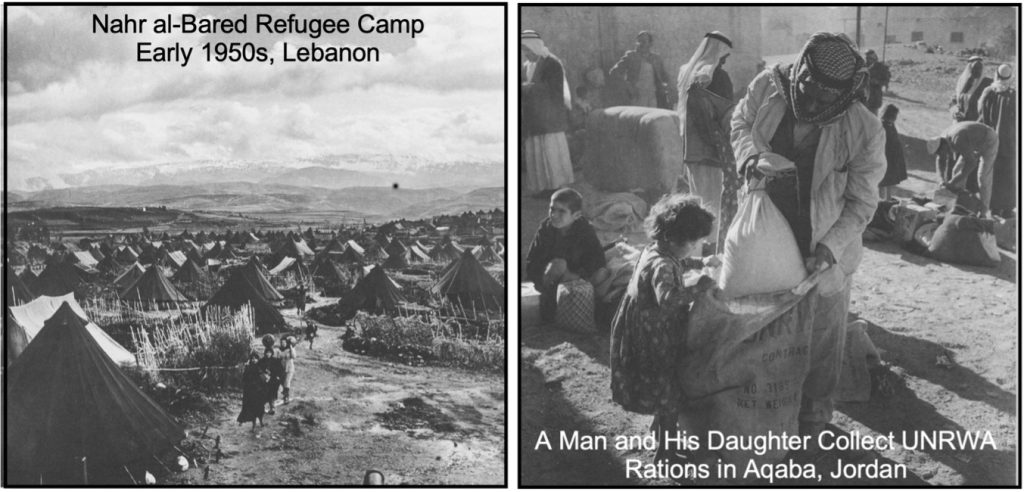

(7) UNRWA, necessary but not sufficient, had not yet been defunded for spurious reason.

Against Erasure is a powerful testament to a vibrant, self-aware, multicultural, and hospitable Palestine that existed for a long time while continuing to cultivate the western arc of the Fertile Crescent, whatever is said these days.

Against Erasure begins with a list of 418 Palestinian villages destroyed in the War of 1948-1949. This brings us to Khirbet Khizeh, a story told about a day in the life of a unit – apparently the size of a platoon (20-50 soldiers) – of the Israeli Army in 1948 as it fulfills its order to depopulate the Palestinian village called Khirbet Khizeh. As in any such group, the attitudes and motivations of the soldiers vary. The narrator wonders at the sense of it all…Why are we doing this? What can these people – women, children, the old, the blind – do to us? Why can’t we live together? Several of his comrades have less than no sympathy or respect for the Palestinian Arabs, the Other, and wish only to follow orders and complete their mission to round up and transport the remaining villagers away, never to return (p. 71-72):

Only rarely did a single cry burst forth and open pent-up hearts and tears…However, when a stone house exploded with a deafening thunder and a tall column of dust – its roof visible…floating peacefully, all spread out, intact, and suddenly splitting and breaking up high in the air and falling in a mass of debris, dust, and a hail of stones – a woman, whose house it apparently was, leapt up, burst into a wild howling and started to run in that direction, holding a baby in her arms, while another wretched child who could already stand clutched the hem of her dress, and she screamed, pointed, talked, and choked, and now her friend got up, and another…One of our boys moved forward and shouted at her to stand still. She stifled her words with a desperate shriek beating her chest with her free hand. She had suddenly understood, it seemed, that it wasn’t just about waiting under the sycamore tree to hear what the Jews wanted and then to go home, but that her home and her world had come to a full stop, and everything had turned dark and was collapsing; suddenly she had grasped something inconceivable, terrible, incredible, standing directly before her, real and cruel, body to body, and there was no going back. But the soldier grimaced as though he was tired of listening, and he shouted at her to sit down with the others…(but)…she left him behind and started running heavily toward the site of the explosion.

I wish I could read this book in the Hebrew. S. Yizhar’s sentences rival those of Faulkner in their never-ending flow of meaning. His story is always in the foreground. As noted in the Afterword by David Shulman, Khirbet Khizeh is a “canonical text…by the first major writer to describe in credible, unforgettable detail one emblematic example of the expulsion of Palestinian villagers from their homes by Israeli soldiers, acting under orders, in the last months of the 1948-1949 war…that cuts right through the nationalist prevalent myth that, like all nationalist myths, blames everything unpalatable on the ever-available ‘enemy.’” This is what the enemy is for. And this is the way of war, the reason for war, the justification for war, in every place at every time. It is also wrong. Besides, the “bad guy” is just as likely to look back at you from your mirror in the morning as he is to see you through binoculars on the field of battle.

Thus, war is never the answer to a properly posed question. But what of the improperly posed questions that present themselves without surcease and demand an answer? Their terms must be changed, they must not be accepted, and they must not be answered as given. Finally, both Arabic and Hebrew have well known words for their own defining “Catastrophe.” Each of these was a human creation, neither was necessary, and nothing justifies the one or the other. This must stop. Now. But how?

Notes

[1] As the working class of Europe succumbed to war fever along nationalist lines, the Second International dissolved in 1916.

[2] In my memory that is exactly how my Aunt Marie put it. She had been a schoolteacher in a 3-room rural school in the 1920s (the school closed during the Great Depression) and was a stickler for details. And grammar. She had learned about Bertrand Russell from her one year in a nearby Normal School. He came up when she asked me which book I had recently read most recently: The collection of essays entitled Why I Am Not a Christian, which she took in stride as the good Christian woman with a sense of humor that she was. She also asked me if I had met the granddaughter of a local friend of hers, who was also attending the same “flagship” state university as one of 25,000 other students. Alas, the answer to that was “no,” which surprised her every time she asked for the next several years.