There’s lots of talk these days about whether we’re in a recession or not. This has been muddied by the fact that the Biden Administration has made an official declaration that this determination is based on a vote by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), not the more popular rule of “two successive negative quarters of GDP.”

As usual, I will not get political, but I will say that I thought the White House issuing that statement was a bad move, as it simply continues to polarize the country. But, ignoring the fact that the administration messed up by making the statement, it’s still worth digging into whether the statement is true and what it means for where we are economically, both from a technical standpoint and a realistic standpoint.

How Are Recessions Determined?

Let’s start with the question of how and by whom recessions have traditionally been determined, and from there, we can jump into whether I think we’re currently in a recession.

Yes, NBER is the organization that has historically been the final arbiter of when a recession starts and ends. They have been dating recessions since the late 1920s and created their recession dating committee in 1978. So, they’ve been doing this for nearly a century and formalized the process nearly half a century ago.

They are a non-partisan organization (I’ve never heard any suggestion from either party they weren’t) and has a group of bi-partisan economists who meet whenever they feel it’s necessary to make determinations, such as whether we’re currently in a recession, where the trough of the recession was, or whether a recession has ended.

If you use the FRED (St. Louis Federal Reserve) website to track economic data, you’ve probably noticed that there are gray vertical bars throughout all the graph timelines that denote recessions. These grey bars—including where they start and end—are determined by NBER.

Now, you might ask, “if they don’t use two consecutive negative quarters of GDP, how do they determine if we’re in a recession?”

Well, it’s a bit more nuanced than any single piece of data (as it should be). Their official criteria for a recession is “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months. The committee’s view is that while each of the three criteria—depth, diffusion, and duration—needs to be met individually to some degree, extreme conditions revealed by one criterion may partially offset weaker indications from another.”

But, here’s the important point:

NBER doesn’t attempt to make real-time calls on recessions. It often takes them months or even longer to make a declaration, as they view their job to historically document economic events, not to call them as they happen. For that reason, the media has gotten comfortable using the “two successive quarters of negative GDP” rule to avoid waiting for NBER to make a determination.

This leads to the obvious question:

Has NBER’s definition of recession ever deviated from the “two successive quarters of negative GDP” definition?

The answer is yes. In fact, it’s happened in two of the past three recessions. In 2001, we saw negative GDP in Q1 and Q3, but not Q2, so we never had consecutive quarters of negative GDP in 2001. But, a recession was declared. During the Great Recession, NBER called a recession starting in December 2007, despite the fact that we didn’t have two consecutive negative quarters of GDP until the end of 2008. Neither of these recessions were officially declared based on two successive quarters of negative GDP.

To finish up an earlier point I was making, NBER often doesn’t meet until well after we start to see recessionary effects on the economy. In many cases, it will declare a recession or a trough well after the occurrence. This makes sense, as it’s often difficult to observe economic shifts in real-time simply because we don’t get economic data in real estate. It can take weeks, months, or even several quarters to get historical data and to put the pieces together to determine exactly what happened in the past.

All that said, I’m perfectly comfortable allowing NBER to ultimately declare recessions, as they’ve been pretty good about it in the past and, with the exception of the misstep by the current administration, there’s never been any partisan push-back from either side.

Which leads us to this question: Does an official declaration of a recession even really matter?

“Recession” is just a word and it doesn’t change any official policy. Isn’t it more important to have a handle on how the economy impacts the people and the businesses in this country so that we can adjust our financial decisions, regardless of whether an official recession has been declared?

I believe so, and I would look at a number of factors to make a personal determination of whether or not we should be considering the U.S. as currently in a recession.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Let’s start with the one everyone likes to look at: GDP. While I’m a big fan of looking at GDP numbers to determine the health of the economy, it’s important to be aware of situations where the numbers may not be fully representative of the current state of the economy. For Q1 and Q2 of this year (both negative GDP), there were a couple of idiosyncrasies in the data worth noting.

Percent Change of Real GDP (2017-2022) – St. Louis Federal Reserve

First, thanks to supply chain issues in 2021, many businesses stocked up on inventory in Q4 last year, spending a ridiculous amount of money to pack their warehouses. This led to GDP growth to the tune of 6.9% during Q4, the second highest since the Great Recession. But, with warehouses packed with inventory, businesses haven’t had to spend nearly as much money in the first half of this year and that reduction in business spending accounted for a large amount of the GDP drop between Q4 last year and Q1/Q2 this year.

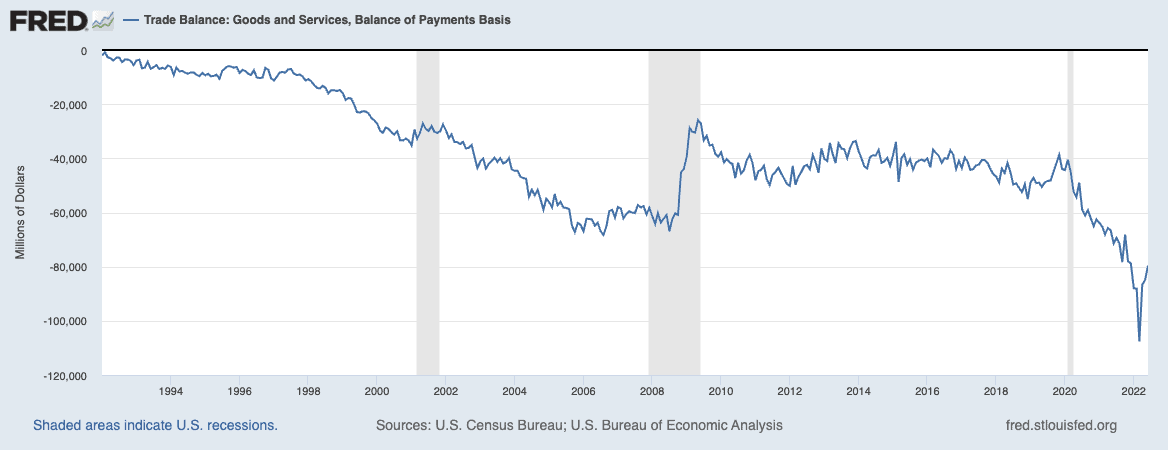

Second, trade plays a big part in GDP. Exports boost GDP numbers. Imports hurt GDP numbers. Thanks to a historically large trade imbalance since mid-2020 (and hitting its peak in March of this year), GDP has looked worse than it normally would with more typical trade imbalances. While heavy importing isn’t indicative of a weak economy (just the opposite, in fact), it hurts GDP and makes the economy look weaker than it otherwise would.

Trade Balance (1992 – 2022) – St. Louis Federal Reserve

Trade Balance (1992 – 2022) – St. Louis Federal Reserve

So, when it comes to GDP, yes, we’ve seen two successive quarters of negative growth. But, had just the two factors I mentioned above been normalized, it’s nearly certain that GDP would have been positive in both Q1 and Q2 of this year.

Unemployment

This is probably the most important metric to look at when it comes to economic health simply because it’s the most indicative metric of the financial stability of Americans. While it may change soon, there is no argument that employment metrics continue to look strong.

The most common unemployment metric, U3 unemployment, is sitting at 3.6%, the same as the historic lows we saw just before the pandemic began. The total number of unemployed people looking for work sits at about 5.9 million. Again, near historic pre-Covid lows. While unemployment claims have ticked up in the past few weeks, 1.6 million claims are still near the historic pre-Covid lows.

Long story short, while unemployment data has a lot of caveats in this post-Covid world, there’s no situation in which we can say the current unemployment numbers aren’t still very strong.

Inflation

While high inflation is certainly a major pain point for both consumers and businesses, it’s actually an indication of an economy that hasn’t yet weakened.

Don’t get me wrong—the increase in interest rates is likely to drive inflation down and take the economy with it—but this hasn’t happened yet. The big question remains about whether inflation is mostly demand-side—driven by strong consumer spending. Or supply-side—driven by supply chain issues. I personally believe that we’re still seeing major supply chain issues, which are leading to the spike in inflation, but many people will still argue that inflation is being driven by strong consumer demand.

If that’s the case, this is actually an indication that we have not yet entered a recession and that consumers are still relatively healthy.

Yield Curve, Bond Rates, and Mortgage Rates

There are plenty of other economic metrics that we can look at to determine whether the economy is still holding up or whether we’re in the midst of a downturn, and without going into too much boring detail, the takeaway is that things are still looking as if we haven’t gone over the cliff.

The yield curve is flattened/inverted, which is a bad sign. But, it’s historically a sign of what’s to come, not a sign of where we are today. Bond and mortgage rates are leveling and dropping, indicating that risk premiums are dropping, which is a sign of investor confidence. Not necessarily confidence that everything is peachy, but confidence that we aren’t going to face big surprises from the market or the Fed.

Consumer Sentiment

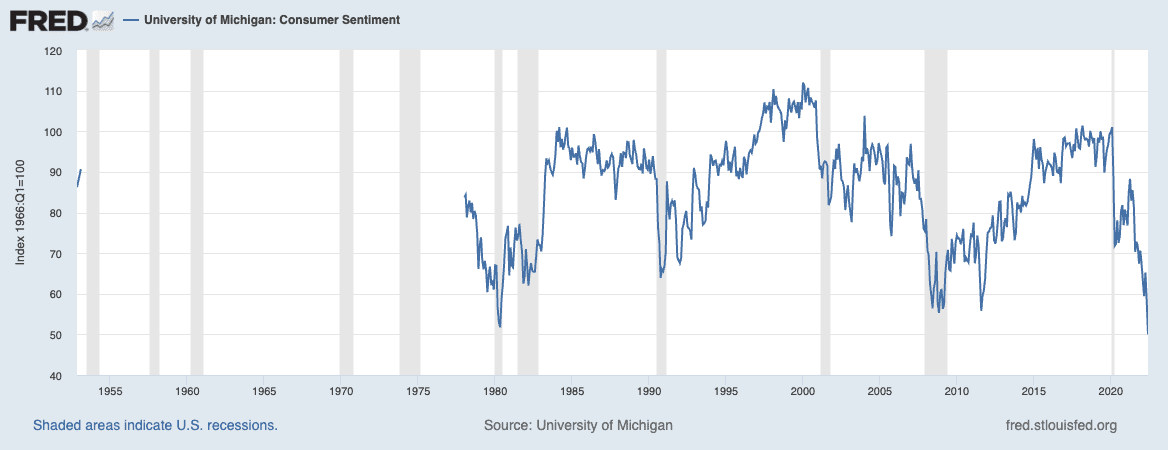

The final metric I’m going to touch on is consumer confidence. While I saved this one for last, in many respects, it’s the most important. Not because it’s necessarily an indication of what’s going on in the economy, but it’s an indication of what people think is going on in the economy. In many ways, that’s more important than what’s actually going on because consumer sentiment will drive consumer habits, which will determine where the economy is headed.

So, where is consumer sentiment?

In the toilet. Specifically, the worst we’ve seen in the 45 years that the data has been tracked. June numbers were even worse than the depths of the 2008 recession. Again, while I would use this to determine the current health of the economy, it’s definitely an indication of where the economy is headed and potentially how quickly.

University of Michigan: Consumer Sentiment (1978 – 2022) – St. Louis Federal Reserve

University of Michigan: Consumer Sentiment (1978 – 2022) – St. Louis Federal Reserve

Conclusion

So, would I say that we’re currently in a recession?

Well, suppose you were to remove that last data point, consumer sentiment. In that case, I think it would be hard to argue that the economy is in a place where we could say that there’s been a significant widespread decline in economic activity. In other words, not a recession.

But I would give that consumer sentiment metric a good bit of credence. With that number so strikingly low, I don’t believe we’re currently in a recession, but I would certainly consider that we are likely on the verge of one. We should assume that most Americans will start making financial decisions that would indicate we are in one.

Long story short, while we can argue all day about whether we’re in a recession or not, there’s little doubt that many Americans are getting ready to start acting as if we’re in one.

Note By BiggerPockets: These are opinions written by the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of BiggerPockets.