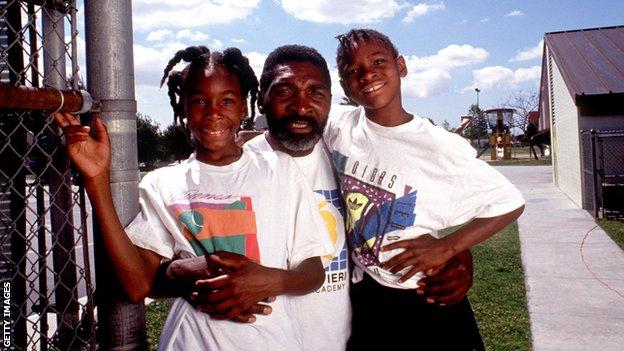

As the story goes, Serena Williams’ rise began before she was born.

In 1979, her father Richard watched a women’s tennis match on TV and saw the Romanian player Virginia Ruzici win $40,000 – about $4,000 more than his annual salary.

“I went and told my wife we had to have two more girls and make them tennis players,” he recalled, 20 years later. “I was 37 and knew nothing about tennis but I thought we could teach them and they could win the US Open.”

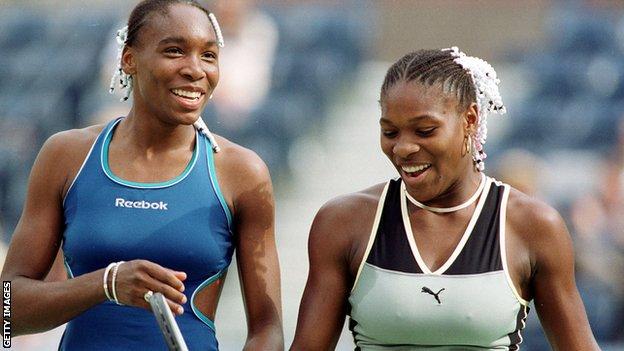

On 26 September 1981, Williams arrived – 15 months after her sister Venus. By the time the pair turned pro in the mid-1990s they were already making waves.

“There was a rage inside these two little kids,” says Rick Macci, the Florida-based coach who helped guide them through their developmental years.

“They were just ready. I called it when they were nine, 10 years old. I said: ‘They’re gonna be world number one and they’re going to transcend the sport.'”

In August 1999, the smart money was on Venus making the big breakthrough. A tall and imposing player, the 19-year-old had already racked up seven titles. She was third in the WTA rankings.

But Serena would get there first. Her victory at the US Open that year saw a future sporting legend announced to the world.

Now, 23 years later, she is almost done.

“I hate it,” she wrote last month of her impending retirement. “I don’t want it to be over.”

In some ways, it already is. With her 41st birthday looming, Williams can no longer match her own imposing legacy on court.

She has one more stop. From Monday she will return to Flushing Meadows to play in her final US Open, the site of that first Grand Slam title.

Looking back on those two weeks of New York late summer in 1999, the signs were already there of what was to come for Williams. She was irrepressible, unpredictable, matchless. A 17-year-old girl from Compton, poised for greatness.

Williams had made her US Open debut in 1998, when she was knocked out in round three.

This year, things looked different. She breezed through the two opening rounds against fellow American Kimberly Po and Croatia’s Jelena Kostanic.

Her father Richard had already stirred a minor drama, predicting that his daughters would meet in the final. “They’re too fast for the other girls,” he said. “They’re a little too strong for them.”

World number one Martina Hingis replied saying the Williams family had a “big mouth”.

Serena laughed it off.

“Obviously she’s number one, so she can say whatever she would like to say,” she said. Then she smiled widely. “I personally don’t think my mouth is big, if you’re just looking at it.”

In the third round, Williams showed no signs of letting up. She deployed her bruising serve and sprawling court coverage to defeat 16-year-old Belgian Kim Clijsters in three sets.

When Williams won, skipping across the court and throwing her arms to the sky, the crowd erupted, apparently thrilled by the new teen prodigy.

But later, once Serena and Venus had become dominant, the Williams family began to notice a chill from spectators in New York, says sports writer SL Price.

“Venus and Serena’s mother Oracene said they felt for years, for almost 10 years, that the US Open crowds were not behind them,” Price says.

“They felt othered in their own home tournament, just because of the straight identification: a white audience with black players. They were African American women in a white-dominated world.”

The country-club crowds of professional tennis were accustomed to a different sort of player – soft-spoken, demure and white. The Williams sisters stood out.

“I’m tall; I’m black,” Venus had said at her 1997 US Open debut. “Everything’s different about me. Just face the facts.”

Two years after her 1999 victory over Clijsters, Williams met her again in the final at Indian Wells, a tournament in southern California seen by some as the unofficial fifth Grand Slam.

Williams was booed relentlessly throughout the championship match. Rumours – unfounded – had spread that Richard had engineered Venus’ last-minute withdrawal from the semi-final against her sister two days earlier.

In his autobiography, Richard said that racial slurs “flew through the stadium” at him and his daughters. When Williams faulted on serve the crowd clapped. When she won, they jeered. She would boycott Indian Wells for the next 13 years.

“How many people do you know go out there and jeer a 19-year-old?” she said after the match, looking uncharacteristically resigned. “I’m just a kid.”

Back at the US Open of 1999, weeks away from her 18th birthday, the depth of Williams’ talent was becoming obvious.

In the fourth round she met Conchita Martinez. Then 27, the Spaniard had won Wimbledon in 1994.

The years of pro experience seemed at first to favour Martinez, who used deep, punchy shots and heavy topspin to clinch the first set 6-4. But in the second set Williams transformed, unleashing a series of flat and punishing groundstrokes.

“She had a switch – she could flip it,” says Shane Rye, Williams’ former trainer. “That’s what separates the elite from everyone else, and she is the upper, upper echelon of elite elite.”

Closing out what would be her biggest win in a major so far, Williams stared down Martinez before serving an ace – her 12th that day – and claiming the match.

There was Williams’ resilience on display: a stubborn refusal to lose that soon became her trademark; an ability to grit her teeth and battle her way back.

“Richard Williams always said ‘Serena is better because she’s meaner,'” says sports journalist Jon Wertheim. “In retrospect, it was the perfect distillation. She had a fire, that ‘Serena mean’ that got her through a lot of matches.'”

Years later, in September 2017, Williams would endure a harrowing delivery of her daughter, Olympia. An emergency C-section, a life-threatening pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung), and two more surgeries left her bedridden for her first six weeks of motherhood.

It would end up being her longest break from tennis since she was a toddler.

“I’ll never forget that phone call, when she was finally cleared by her doctor to play,” says Rye, who worked with her through her recovery.

“I remember how emotional that was for her.”

It was quite the comeback. Still breastfeeding and suffering from postpartum depression, Williams once again grit her teeth and bore down on court, making it to the finals of two majors in 2018 – Wimbledon and the US Open.

Her burning drive also ignited some spectacular, regrettable on-court flameouts, many at the US Open.

Often these incidents reflected less on Williams than on the sexism still polluting tennis. Her temper almost always paled in comparison to the legendary meltdowns of male players, John McEnroe, Jimmy Connors and Andy Roddick among them.

When Williams was docked a game at the 2018 US Open final after calling chair umpire Carlos Ramos a “thief”, Roddick called it the “worst refereeing I’ve ever seen”.

“I’ve regrettably said worse and I’ve never gotten a game penalty,” he said.

Still, Williams’ protracted dispute with Ramos – a bitter back and forth that lasted almost all of the second set – seemed to rob Naomi Osaka, then 20, of a magic moment: her first major win, and against her childhood idol. During the trophy ceremony, both Williams and Osaka wept.

“I was behind the umpire’s chair at the time and you’re just like ‘here we go again, don’t do this, get it together,'” Price says. “But there’s something about that unpredictability; it’s Serena being Serena.”

Such would be the extent of her later dominance you could almost forget all the champions Williams had to overtake to get there.

In the 1999 US Open quarter-finals she faced off against Monica Seles, her childhood hero, and by then a nine-time major singles winner.

Seles, who had been badly wounded when a fan ran on court and stabbed her in 1993, took the first set.

But a defiant Williams responded fiercely, dominating the rest of the match. When she won, she threw her arms in the air and held them there, spinning slowly to get a look at the crowd. In the stands Richard looked back at her, held up his index finger and mouthed: “Number one, baby.”

It was a similar story in the semi-finals, when Williams took on defending champion Lindsay Davenport, the second seed.

With the score tied in the third set, Davenport blinked first. Williams broke her, to go ahead 4-3. Receiving serve in the next game, Davenport clawed her way back, earning five break points, but Williams held on. She won the next game too, and the match. She was in her first major final.

“Every break point I had, she just hit a huge, huge serve,” Davenport said at the time. “I never got a second serve, I don’t think, slower than 105 [mph].”

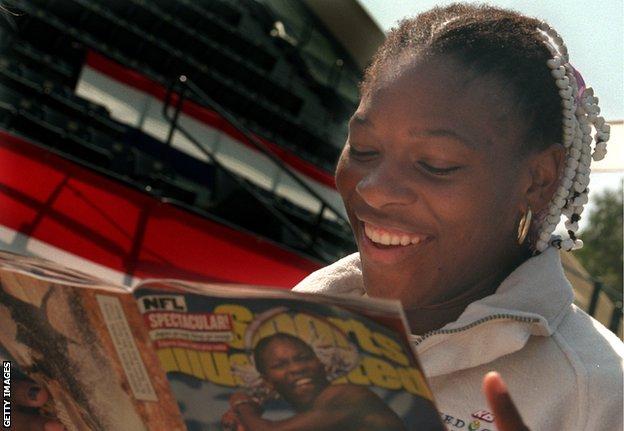

Williams, meanwhile, basked in her burgeoning celebrity, telling assembled media she was collecting pictures of herself from national newspapers.

“I mean, I touch everyone,” she said. “Everyone wants to see me. I don’t blame them. Go get a look at Serena.”

Up until that summer of 1999, most people had ignored Richard Williams’ prediction that Serena would be the better player of his two tennis prodigies.

But then the birth order was subverted: Venus lost to Martina Hingis in the semi-finals. And so while Serena walked on court at Arthur Ashe to play – defiant stare, white beads in her hair – Venus watched from the stands, black hoodie tugged tight around her face.

It was a good match-up: Williams, a force of strength and poise, against Hingis, a brilliant tactician who ran famously cool.

“We were like yin and yang,” says Hingis, who was herself only 18 but already a five-time Grand Slam winner.

Williams took the first set 6-3. She looked untouchable, outpacing and outthinking Hingis. In the second she stormed into a 5-3 lead. Then suddenly she cracked, fumbling two championship points.

“She was always leading, I felt like always behind, being defensive, but I was reborn when she missed those two match points,” Hingis said that day.

By then, Williams looked exhausted. Standing behind the baseline, she used her bright yellow dress to wipe the sweat from her mouth. She stared blankly at the ground in front of her, awash in sunlight and stadium glare, and bounced the ball a few more times than usual before winding up to serve.

From 3-5 down, Hingis won the next three games to take a 6-5 lead, Williams adding to a growing tally of unforced errors.

For the first time, Hingis was in the ascendency, her face relaxing into a slight smile. Williams was forced to defend a set point in her service game before pushing the set to a tie-break.

But from there, Williams seized back control. As the intensity mounted, her strokes got better.

“When I get into a tie-break, I feel that I never lose,” Williams told reporters after the match. “I feel that I can’t lose.”

Hingis now alternated between a look of grim concentration and amusement.

At some points she looked like she might laugh, bowing her head and shaking it slightly as if she too was amazed by the singular power of a resurgent Williams.

“Serena was the fiercest player for me. I didn’t like playing her,” Hingis says. “Because the big points, the big moments, you could never think she would slow down, or have any mental weakness. I had a break point here and there and I had my chances, but then she would just hit an ace, you know?

“That was very frustrating on my side, but that’s why she was Serena Williams.”

Up 6-4 in the tie break, Williams was serving for the title.

She took her time. She closed her eyes for a moment, face still, shoulders heaving, before making her way to the baseline. Smaller, more reserved than we know her now, she was already unblinkingly self-assured. The greatest female tennis player in history, not yet fully formed.

The final rally didn’t last long – a searing serve from Williams and two backhand returns before Hingis sent the ball out.

Williams looked momentarily stunned, stumbling backward and clutching her chest. Twenty thousand people roared.

She had become the first black American since Arthur Ashe in 1975 to win a major singles title, and the first black American woman since Althea Gibson in 1958.

Richard lifted a small camera to his eye, capturing the moment that launched the titanic career of his daughter.

“Serena Williams has been dominant,” says Price. “She’s been at this level that is beyond most people on earth.

“And now it’s that decline, that descent, joining the rest of humanity.”