Yves here. While this article on the acquisition of human language, I am not sure about the proposition that only humans have syntax, as in can assemble communication units in a way that conveys more complex meanings.

Consider the crow, estimated at having the intelligence of a seven or eight year old. There are many studies of crows telling each other about specific people, demonstrated by a masked experimenter catching a crow (which they really do not like), then being hectored by crows who were not party to the original offending conduct:

So how does one crow tell another crow that a particular human visage is a bad person? Perhaps one crow sees another crow scold a particular person. But particular masks elicit consistent crow catcalls for many years after the offending behavior. It still might be very good memories plus observation by their peers. But the detail from this study suggests a more complex mechanism:

To test his [Professor John Marzluff of the University of Washington’s] theory, two researchers, each wearing an identical “dangerous” mask, trapped, banded and released 7 to 15 birds at five different sites near Seattle.

To determine the impact of the capture on the crow population, over the next five years, observations were made about the birds’ behaviour by people walking a designated route that included a trapping site.

These observers either wore a so-called neutral mask or one of the “dangerous” masks worn during the initial trapping event.

Within the first two weeks after trapping, an average of 26 per cent of crows encountered scolded the person wearing the dangerous mask.

Scolding, says Mazluff, is a harsh alarm kaw directed repeatedly at the threatening person accompanied by agitated wing and tail flicking. It is often accompanied by mobbing, where more than one crow jointly scolds.

After 1.25 years, 30.4 per cent of crows encountered by people wearing the dangerous mask scolded consistently, while that figure more than doubled to around 66 per cent almost three years after the initial trapping.

Marzluff says the area over which the awareness of the threat had spread also grew significantly during the study. Significantly, during the same timeframe, there was no change in the rate of scolding towards the person wearing the neutral mask.

He says their work shows the knowledge of the threat is passed on between peers and from parent to child….

Marzuff says he had thought the memory of the threat would lose its potency, but instead was “increasing in strength now five years later”.

“They hadn’t seen me for a year with the mask on and when I walked out of the office they immediately scolded me,” he says.

In another example (I can’t readily find it in the archives) a city in Canada that was bedeviled by crows decided to schedule a huge cull. They called in hunters. They expected to kill thousands, even more.

They only got one. The rest of the crows immediately started flying higher than gun range.

Again, how did the crows convey that information to each other, and so quickly too?

The extend of corvid vocalization could support more complex messaging. From A Murder of Crows:

Ravens can in fact produce an amazing variety of sounds. Not only can they hum, sing, and utter human words: they have been recorded duplicating the noise of anti-avalanche explosions, down to the “Three…Two… One” of the human technician. These talents of mimicry reflect the general braininess of corvids – which is so high that by most standards of animal assessment, it’s off the scale.

By Tom Neuburger. Originally published at God’s Spies

While we wait for news — or not — from the Democratic convention, I offer this, part of our “Dawn of Everything” series of discussions. Enjoy.

Adam names the animals

Oh! Blessed rage for order, pale Ramon,

The maker’s rage to order words of the sea,

Words of the fragrant portals, dimly-starred,

And of ourselves and of our origins

—Wallace Stevens, “The Idea of Order at Key West”

We’re headed for prehistoric times, I’m sure of it, and as a result, human prehistory has been a focus of mine for quite a few years.

What were our Stone Age lives like? And who lived them? After all, “we” might be just homo sapiens, maybe 200,000 years old; or “we” might be broader, including our contemporary cousins, homo neanderthalensis, or even the ancient, long-lived homo erectus. Erectus had very good tools and fire perhaps. Neanderthals were much like us — we interbred — though evidence suggests, while they probably had some kind of language, we were far smarter.

One of the bigger questions is the one David Graeber and David Wengrow took on in their book The Dawn of Everything: Was it inevitable that the myriad of Stone Age cultures resolve to the single predatory mess we’re now saddled with?

After all, it’s our predatory masters — the Kochs, the Adelsons, the Pritzgers, the Geffens, their friends — whose mandatory greed (which most of us applaud, by the way) have landed us where we are, mounting the crest of our last great ride down the hill.

What’s the Origin of Syntax?

One set of mysteries regarding our ancient ancestors involves their language. How did it emerge? How did it grow? If the direction of modern languages is to become more simple — in English, the loss of “whom”; in French the loss of “ne”; the millions of shortenings and mergings all languages endure — how did that complication that we call syntax first come about?

The most famous theory is the one by, yes, Noam Chomsky, that humans are born with a “universal grammar” mapped out in our brains, and learning our first language applies that prebuilt facility to what we hear. His argument: No child could learn, from the “poverty of the stimulus” (his or her caregiver’s phrases), all the complexity of any actual language.

There’s, of course, much mulling and arguing over this topic, especially since it’s so theoretical.

Something that’s not theoretical though is this: a group of experiments that shows that syntax evolves, from little to quite complex, all on its own, as a natural byproduct of each generation’s attempt to learn from their parents.

The process is fascinating and demonstrable. The authors of this work have done computer simulations, and they’ve worked with people as well. The results seem miraculous: like putting chemicals into a jar, then thirty days later, finding a butterfly.

The Iterated Learning Model

I’ll explain the experiments here, then append a video that’s more complete. (There are others. Search for Simon Kirby or Kenny Smith.) The root idea is simple. They start where Chomsky starts, with the “poverty of the stimulus,” the incomplete exposure every child gets to his or her first language. Then they simulate learning.

Let’s start with some principles:

- All language changes, year after year, generation to generation. The process will never stop. It’s how we get from Chaucer to Shakespeare to you.

- Holistic language vs. compositional language: That’s jargon for a language made of utterings that cannot be divided in parts (holistic), versus one made up of those that can (compositional).For example, “abracadabra” means “let there be magic,” yet no part of that word means any part of its meaning. It’s entirely holistic. The whole word means the idea; it has no parts. “John walked home,” on the other hand, is compositional; it’s made up of parts that each contain part of the idea. (Note that the word “walked” is compositional as well: “walk” plus “ed”.)

This matters for two reasons. First, the closest our monkey cousins get to a language is a set of lip smacks, grunts, calls and alerts that each have a meaning, but can’t be deconstructed or assembled. If this is the ultimate source of our great gift, it’s a truly holistic one. No part of a chimp hoot or groan means any part of the message. The sound is a single message.

Because of this fact — the holistic nature of “monkey talk” — our researchers seeded their experiment with a made-up and random language, entirely holistic. Then they taught this language to successive generations of learners — both people and in simulations — with each learner teaching the next as the language evolved.

Remember, the question we’re interested in is: How did syntax start? Who turned the holistic grunts of the monkeys we were, into the subtle order of our first real languages.

The answer: Nobody did.

The Experiments

All of the experiments are pretty much alike; they just vary in tweaked parameters. Each goes like this:

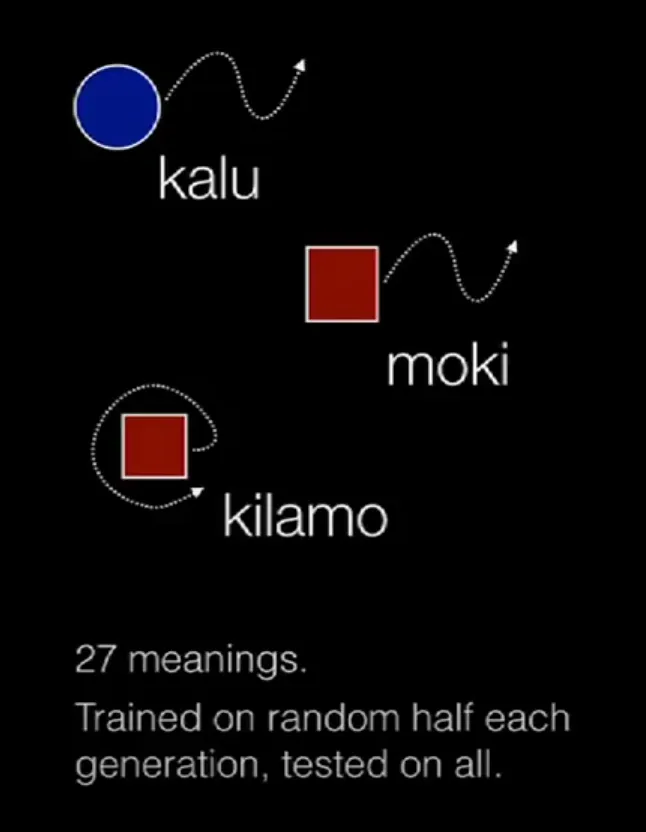

Step one. Create a small artificial, holistic language made up of nonsense words, where each word “means” a small drawing. In this case, each drawing has three elements: a shape, a color and a motion. Here are a few:

Since each “meaning” (symbolic drawing) has a color, a shape and a motion, and since there are three colors (blue, red, black), three shapes (circle, square, triangle), and three motions (straight, wavy, looping), there are 27 ideas (symbols) in the language and thus 27 words. Again, the words are randomly assigned.

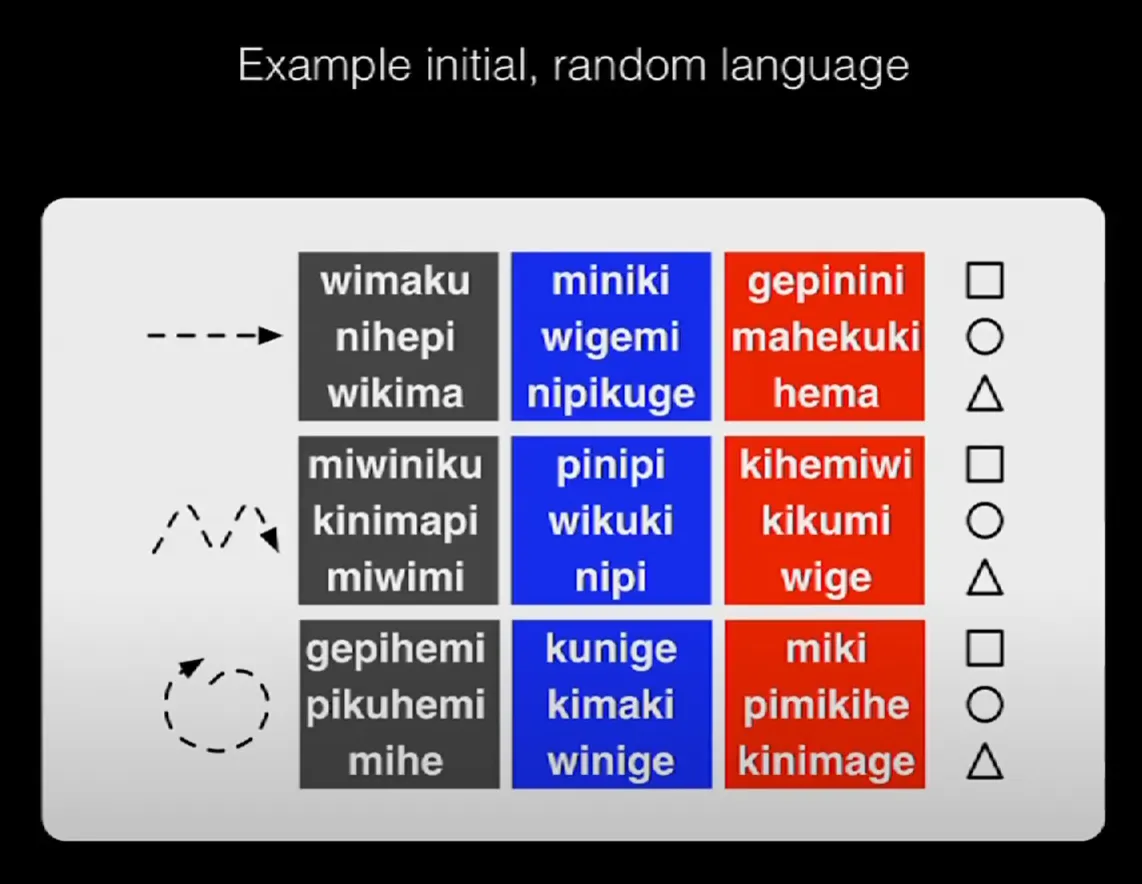

Following this pattern, a 27-word language might look like this:

A 27-word language where each word refers to a colored shape-with-motion. “Wimaku” means “black square with straight motion,” etc.

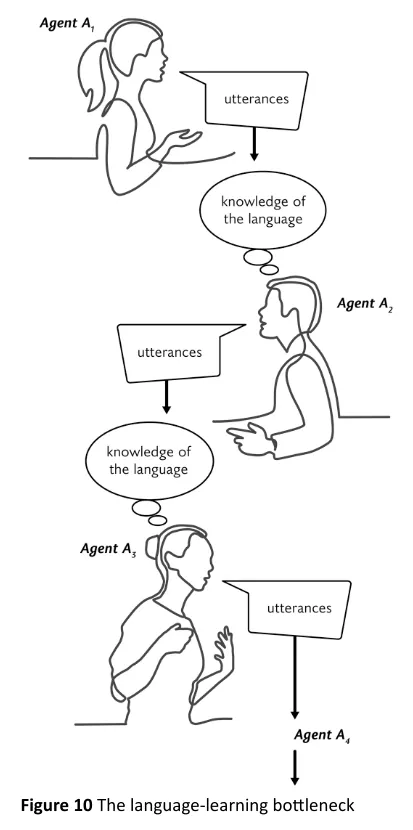

Step two. Teach the first “agent” (A1, the first learner) the whole language.

Step three. Let A1 teach A2, the second learner, just half of the language.

Step four. Test A2 on the whole language. She is shown all of the “meanings” (the symbols) and has to try to guess the names of the ones she doesn’t know.

Step five. Let A2 teach A3, the third learner in the chain, a random half of her language, filtering out duplicated words, words with two “meanings” (two associated symbols).

Step six. Test A3, as before, on the whole language. Show him all of the symbols and ask him to guess the names he hasn’t yet learned.

Step seven. Repeat the above as often as you like.

From Steven Mithen, The Language Puzzle

The researchers did this with people and by computer simulation. The beauty of a simulation is that you can iterate the process endlessly if you like (the number of generations from Sumerian writing to now is about 200). You can also vary parameters like population size (how many teachers and learners in each generation), as well as the bottleneck size (does each generation teach half the language, a third of it, or three-fourths?).

The Results

The results were astounding. The bottleneck — each student’s incomplete learning — always creates, over time, a compositional, syntactical language. As Steven Mithen put it in Chapter 8 of his book The Language Puzzle, the work that put me onto this idea:

Although rules [of a language] gradually change over time, just as the meaning and pronunciation of words change, each generation learns the rules used by the previous generation from whom they are learning language. As an English speaker, I learned to put adjectives before nouns from my parents, and they did the same from their parents and so forth back in time. That raises a question central to the language puzzle: how did the rules originate? Were they invented by a clever hominin in the early Stone Age, who has left a very long legacy because their rules have been copied and accidentally modified by every generation of language learners that followed? No, of course not. But what is the alternative?

The answer was discovered during the 1990s: syntax spontaneously emerges from the generation-to-generation language-learning process itself. This surprising and linguistically revolutionary finding was discovered by a new sub-discipline of linguistics that is known as computational evolutionary linguistics. This constructs computer simulation models for how language evolves by using artificial languages and virtual people.

Here’s what that looks like in a lab with people. Look again at the “language” above, the 27 words. At this stage, the words are holistic — “miniki” means “blue square straight” and “wige” means “red triangle wavy.” No part of a word means part of the associated symbol.

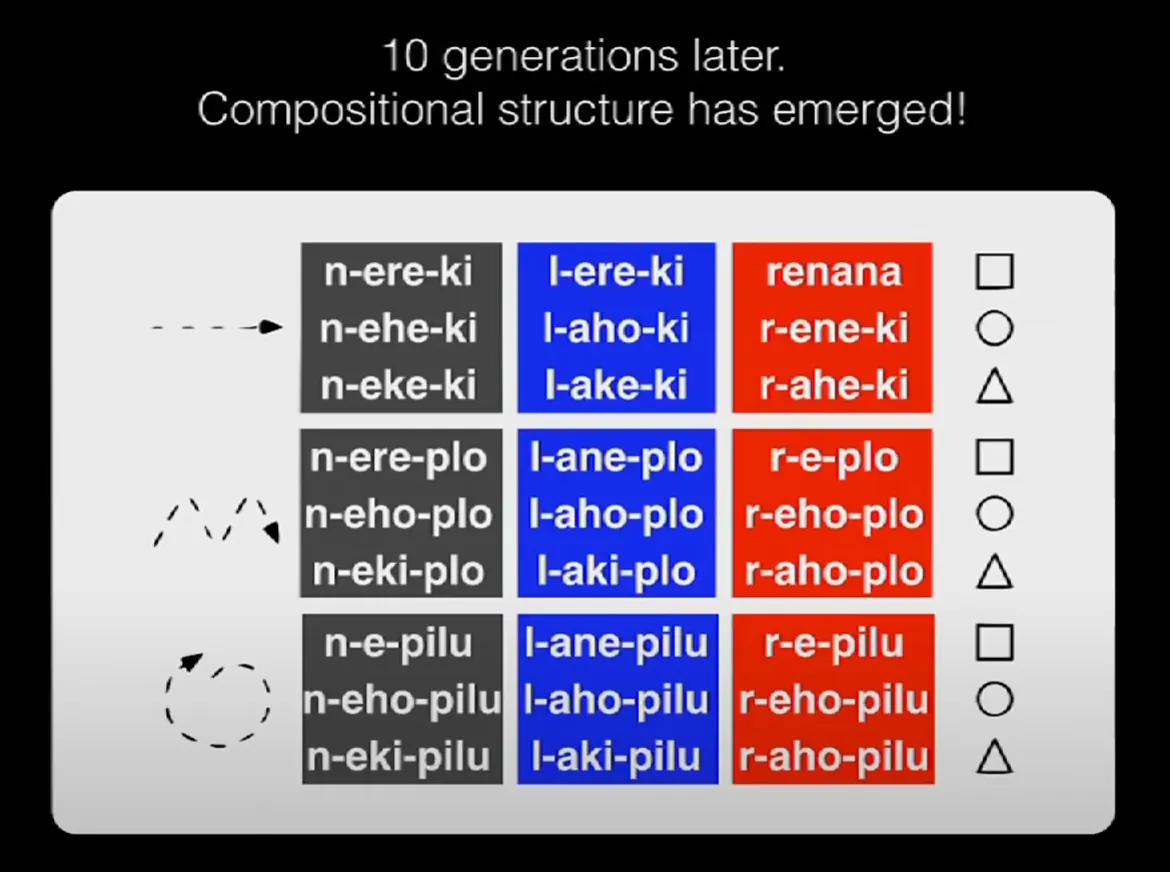

After just ten generations, this is what the language evolved into:

The hyphens were added to this slide for informational purposes; they weren’t part of the actual words. Anything starting with “n” is black in color; “ere” in the middle is starting to mean a square; anything ending in “plo” has a wavy motion.

Ten generations more and this would be smoother. Again, the order, the syntax, its compositional nature, emerges from the process itself, from the iterative act of one generation learning, then teaching, and the next group doing its best to fill in the blanks.

For a video describing these experiments, see below. I’ve cued it to start in the middle, at the point of interest.

I’d be wrong to say there aren’t those who disagree, but this is lab work, not theory, and repeatable, both with SimCity scenarios and actual people.

For me, it answers a question I’ve had almost forever: What first gave languages order? The answer: Speech itself.