Economist Mario Draghi has held a lot of roles: Goldman Sachs executive, the European Central Bank president, and unelected prime minister of Italy. He’s now continuing his decades-long mission to remake Europe into a neoliberal paradise for the financial class as a sidekick to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

That’s the best way to read his much-anticipated September report titled “EU Competitiveness: Looking Ahead,” which was requested by von der Leyen and coincidentally gave an economist’s stamp of approval to all of Ursula’s goals as commission president. It’s also why the roadmap laid out by Draghi is so important: it reveals much of the policy goals of the EU, which have long been underway and are set to continue. And it’s not pretty.

I wrote about the nonsensical energy policy contained in the report and alluded to Draghi’s ideas on productivity in a recent review of Ursula’s China “de-risking” strategy. Here I want to focus on the central theme contained in the title: competitiveness.

What are Draghi and company talking about when they talk about competitiveness? More local production, better quality of life for citizens, more competition? Of course not. It’s the opposite. And it promotes the doubling down on self-created crises like energy policy and looking to create new ones via a trade war with China. While tariffs on Chinese products aren’t necessarily a bad idea, it’s difficult to argue that the EU is really trying to protect industry for three reasons:

- If they were, they would be trying to get Russian gas flowing again. The lack of it has made EU manufacturing uncompetitive.

- They cannot simultaneously pursue neoliberal policies like austerity and an industrial policy. They’re certainly doing the former while saying they want to do the latter.

- They are escalating a trade war with China while being wholly unprepared as many products they rely on from China like certain drugs, chemicals and materials have no substitutes.

What Ursula, Draghi, and the European financial-political class are after isn’t more competitiveness at all; they’re seeking to complete the makeover of the EU into a neoliberal paradise (or hellhole depending on your viewpoint), which means less democracy, the further destruction of labor, and looking a lot more like — if not outright owned by — the US.

Europe now relies on the US for security, the US for (fossil) energy and the US for demand …

to rephrase an old trope about Germany https://t.co/0lxEdquQCn pic.twitter.com/m2aaIiYQn5

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) October 18, 2024

Let’s look at some key points of Draghi’s prescription for more competitiveness.

More Concentration

The EU says it needs a ton of money for investment. Indeed that is what Ursula’s Commission has been calling for, that’s what the big report from Mario Draghi called for, and what hundreds of other similar reports want too, but it does not appear to be forthcoming.

So what they turn to next is a walling off from the East and a wholesale selloff to the US in order to help create the large firms they argue are necessary to build technological supremacy. How is this strategy already playing out?

The EU-US Trade and Technology Council is currently hard at work getting EU regulations in line with American interests. The EU is already dominated by US IT companies that supply software, processors, computers, and cloud technologies and we can expect more of that as Draghi and Ursula call for more mergers and acquisitions and more US private equity and venture capital.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken calls the United States’ allies and partners “force multipliers” and “a unique asset.”

Assets, indeed. As more European companies struggle due to high energy costs and long-stagnant economies driven in large part by the EU’s obsession with austerity, they’re increasingly becoming the focus of merger and acquisition specialists from the US. CDI Global reports the following:

In recent years, a marked increase in cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) by US companies in Europe has emerged as a notable trend. This surge in transatlantic investment signifies a strategic shift by American firms, grounded in the USA, aiming to harness the diverse advantages and lucrative opportunities presented by European markets. From established corporate giants seeking expansion to agile start-ups on the lookout for innovative growth pathways, numerous compelling factors drive US businesses to explore European bargain-hunting ventures…

A significant allure for US companies investing in Europe is the potential for acquiring assets at bargain prices. Economic uncertainties, geopolitical fluctuations, and evolving market dynamics have led to decreased valuations of European companies in recent years. This creates a favorable environment for US investors, allowing them to purchase valuable assets at more attractive prices than those typically found in the US market.

In addition to favorable valuations, Europe offers relatively lower costs associated with labor, research and development (R&D), and operational expenses. European countries often provide substantial subsidies, tax incentives, and grants aimed at fostering innovation and business development, reducing the financial burden on US firms.

US private equity giant Clayton Dubilier & Rice destroyed the UK’s fourth largest supermarket chain in a few short years. Warburg Pincus joined a consortium to snatch up T-Mobile Netherlands a couple years ago. US-based Parker Hannifin is taking private the UK aerospace and defence group Meggitt. Gores Guggenheim grabbed Swedish electric carmaker Polestar.

The private equity firm KKR, which includes former CIA director David Petraeus as a partner, took home the fixed-line network of TIM, Italy’s largest telecommunications provider. German energy service provider Techem was just sold off to the US asset manager TPG, and Germany’s awful economy is increasingly making its companies more likely targets for takeovers. The spooky Silicon Valley company Palantir is already making itself at home in the UK National Health Services, and it’s knocking on the door in Italy. Meera Shah, a senior corporate finance manager at Buzzacott and member of the Corporate Finance Faculty’s board, explains:

“Selling assets into the US has always been a fairly chunky part of what we do, but even with that track record, we’ve seen a significant increase in inbound interest from the US. There have been months where up to one third of the businesses we’ve sold have gone to US buyers.”

Guarding against China and Russia while the US strip-mines Europe is apparently a good thing because letting the US take over Europe means a successful “de-risk” from China and Russia.

Well, except for the people who live in the EU.

Take the example of TIM in Italy. As mentioned it already sold off its fixed line network and plans to unload even more assets soon. Telecom is one sector Draghi focuses on, lamenting the lack of concentration. Europeans have too many options, he says, but this idea that the EU needs consolidation (led by US firms as it so happens) in order to be more competitive begs the question: competitive for whom?

Italy has one of the world’s most competitive telecom markets, with monthly subscriptions for full-fiber landline services, which usually include unlimited Internet, priced as low as €20 to €25, about a quarter of what most US consumers pay.

So could a telecom behemoth that has a monopoly in the US and Europe feasibly be more competitive with Chinese companies? Maybe in profits or company value.

Would it help lead to technological supremacy as the other part of the argument goes? There are reasons to doubt that.

The story of TIM is instructive. The company used to employ 120,000 people compared to 40,000 (and dwindling) today and had “a strong innovative capacity” boosted by cutting-edge subsidiaries such as the Torino-based Centro Studi e Laboratori Telecomunicazioni. The company’s downfall began three decades ago when Italy came under EU control and Telecom Italia was privatized. As journalist Marco Palombi writes at Il Fatto Quotidiano (translation):

However, this disaster began thirty years ago when “the mother of all privatizations” was deemed necessary for Italy to respect the parameters of the Maastricht Treaty. There was no industrial plan, just the requirement to raise cash. It is the first of many financial choices that destroyed an industrial giant.

So the EU helped soften the target up before the US swooped it for the kill. It’s a process that continues today, and upcoming austerity in the EU will do so again:

The four largest €zone countries will all run contractionary fiscal policies in 2025. France, Germany, Italy, Spain represent ~75% of €zone GDP and have tight trade links with others. They will all go for budget cuts when the €zone economy is already weak.

Not far-sighted… pic.twitter.com/GJfDuGOclh

— Philipp Heimberger (@heimbergecon) October 23, 2024

Here I’m going to rattle off some quotes from the Draghi report with limited comment as I think they’re self-explanatory and to keep this post from going too long. One thing to keep in mind when reading Draghi’s wisdom, however, is that automation is considered productivity growth and therefore equals competitiveness.

Less Labor Law for “Innovative” Companies

…the EU should support rapid growth within the European market by giving innovative start-ups the opportunity to adopt a new EU-wide legal statute (the “Innovative European Company”).

This status would provide companies with a single digital identity valid throughout the EU and recognised by all Member States. These companies would have access to harmonised legislation concerning corporate law and insolvency, as well as a few key aspects of labour law and taxation, to be made progressively more ambitious, and they would be entitled to establish subsidiaries across the EU without incorporating separately in each Member State.

Free Rein to AI and Tech Start Ups

Regulatory barriers to scaling up are particularly onerous in the tech sector, especially for young companies [see the chapters on innovation, and digitalisation and advanced technologies]. Regulatory barriers constrain growth in several ways.

First, complex and costly procedures across fragmented national systems discourage inventors from filing Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), hindering young companies from leveraging the Single Market.

Second, the EU’s regulatory stance towards tech companies hampers innovation: the EU now has around 100 tech-focused laws and over 270 regulators active in digital networks across all Member States. Many EU laws take a precautionary approach, dictating specific business practices ex ante to avert potential risks ex post. For example, the AI Act imposes additional regulatory requirements on general purpose AI models that exceed a pre-defined threshold of computational power – a threshold which some state-of-the-art models already exceed.

Third, digital companies are deterred from doing business across the EU via subsidiaries, as they face heterogeneous requirements, a proliferation of regulatory agencies and “gold plating”04 of EU legislation by national authorities.

Fourth, limitations on data storing and processing create high compliance costs and hinder the creation of large, integrated data sets for training AI models. This fragmentation puts EU companies at a disadvantage relative to the US, which relies on the private sector to build vast data sets, and China, which can leverage its central institutions for data aggregation. This problem is compounded by EU competition enforcement possibly inhibiting intra-industry cooperation.

Finally, multiple different national rules in public procurement generate high ongoing costs for cloud providers. The net effect of this burden of regulation is that only larger companies – which are often non-EU based – have the financial capacity and incentive to bear the costs of complying. Young innovative tech companies may choose not to operate in the EU at all.

Less Sovereignty

The lack of a true Single Market also prevents enough companies in the wider economy from reaching sufficient size to accelerate adoption of advanced technologies. There are many barriers that lead to companies in Europe to “stay small” and neglect the opportunities of the Single Market. These include the high cost of adhering to heterogenous national regulations, the high cost of tax compliance, and the high cost of complying with regulations that apply once companies reach a particular size. As a result, the EU has proportionally fewer small and

medium-sized companies than the US and proportionally more micro companies [see Figure 7]. However, there is a close link between the size of companies and technology adoption. Evidence from the US show that adoption rises with firm size for all advanced technologiesxii. Likewise, while in 2023 30% of large businesses in the EU had adopted AI, only 7% of SMEs had done the samexiii. Size enables adoption because larger companies can spread the high fixed costs of AI investment over greater revenues, they can count on more skilled management to make the necessary organisational changes, and they can deploy AI more productively owing to larger data sets. In other words, a fragmented Single Market puts EU companies at a disadvantage in terms of the speed of adoption…

More “Disruption”

A better financing environment for disruptive innovation, start-ups and scale-ups is needed as barriers to growth within the European markets are removed [see the chapters on innovation, and investment]. While high-growth companies can typically obtain finance from international investors, there are good reasons to further develop the financing ecosystem within Europe. Very early-stage innovation would benefit from a deeper pool of angel investors. Ensuring sufficient local capital to fund scale-ups would concentrate the spillovers of innovation within Europe. Increasing the appeal of European stock markets for IPOs would improve funding options for founders, encouraging more start-up activity in the EU. To generate a significant increase in equity and debt funding available to start-ups and scale-up, the report proposes the following measures. First, expanding incentives for business “angels” and seed capital investors. Second, assessing whether further changes to capital requirements under Solvency II are warranted, which establishes capital adequacy rules for insurance companies, and issuing guidelines for EU Pension Plans, with the aim of stimulating institutional investment in innovative companies in selected sub-sectors. Third, increasing the budget of the European Investment Fund (EIF), which is part of the EIB Group and provides finance to SMEs, improving coordination between the EIF and the EIC, and eventually rationalising the VC funding environment in Europe. Finally, enlarging the mandate of the EIB Group to enable co-investment in ventures requiring larger volumes of capital, while also enabling it to take on more risk to help “crowd in” private investors.

Learn from Hyper-globalization which Decimated Labor by Embracing AI which Could Decimate Labor.

The key driver of the rising productivity gap between the EU and the US has been digital technology (“tech”) – and Europe currently looks set to fall further behind. The main reason EU productivity diverged from the US in the mid-1990s was Europe’s failure to capitalise on the first digital revolution led by the internet – both in terms of generating new tech companies and diffusing digital tech into the economy. In fact, if we exclude the tech sector, EU productivity growth over the past twenty years would be broadly at par with the US. Europe is lagging in the breakthrough digital technologies that will drive growth in the future. Around 70% of foundational AI models have been developed in the US since 2017 and just three US “hyperscalers” account for over 65% of the global as well as of the European cloud market. The largest European cloud operator accounts for just 2% of the EU market. Quantum computing is poised to be the next major innovation, but five of the top ten tech companies globally in terms of quantum investment are based in the US and four in China. None are based in the EU.

Overhaul Education “Skills Investment” With a Focus on Training Workers to Become Productive Tools for Capital:

The EU should overhaul its approach to skills, making it more strategic, future-oriented and focused on emerging skill shortages. The report recommends that, first, the EU and Members States enhance their use of skills intelligence by making much more intense use of data to understand and act on existing skills gaps. Second, education and training systems need to become more responsive to the changing skill needs and skill gaps identified by the skills intelligence. Curricula need to be revised accordingly, also involving employers and other stakeholders. Third, to maximise employability, a common system of certification should be introduced to make the skills acquired through training programmes easily understandable by prospective employers throughout the EU. Fourth, the EU programmes dedicated to education and skills should be redesigned, so that the funding allocated can achieve a much greater impact. To improve the efficiency and scalability of skills investments, the disbursement of EU funds should be coupled with stricter accountability and impact evaluation. In parallel, it is proposed to adopt specific interventions to address the most acute skills shortages in technical and STEM skills. A particular focus is needed on adult learning, which will be key to update worker’s skills throughout their lives. Linked to this, vocational training also needs a broad reform across the EU. Specific sectors (strategic value chains) or specific skills (both worker and managerial capabilities) will require complementary targeted interventions. For example, it is proposed to launch a new Tech Skills Acquisition Programme to attract tech talent from outside of EU, adopted EU-wide and co-funded by the Commission and Member States. This programme would combine a new EU-level visa programme for students,graduates and researchers in relevant fields to stimulate inflow, a large number of EU academic scholarships, in particular in STEM subjects, and student internships…

While the Draghi report was almost comical for its refusal to address the reasons behind the EU energy crisis, it was also an incredibly sad read. That’s because it ignores the disadvantages of chasing Draghi and Ursula’s brand of competitiveness and productivity.

The transatlantic crowd doesn’t have to look far for what all these policy prescriptions would mean for Europe: it would become more like the US. And there are plenty of downsides for all the workers who form the backbone of “competitiveness” of such a change.

Draghi actually mentions the healthcare sector as an example of where the US outcompetes the EU. How is that competitiveness measured? By things like productivity and profit. And not, of course, by data like this:

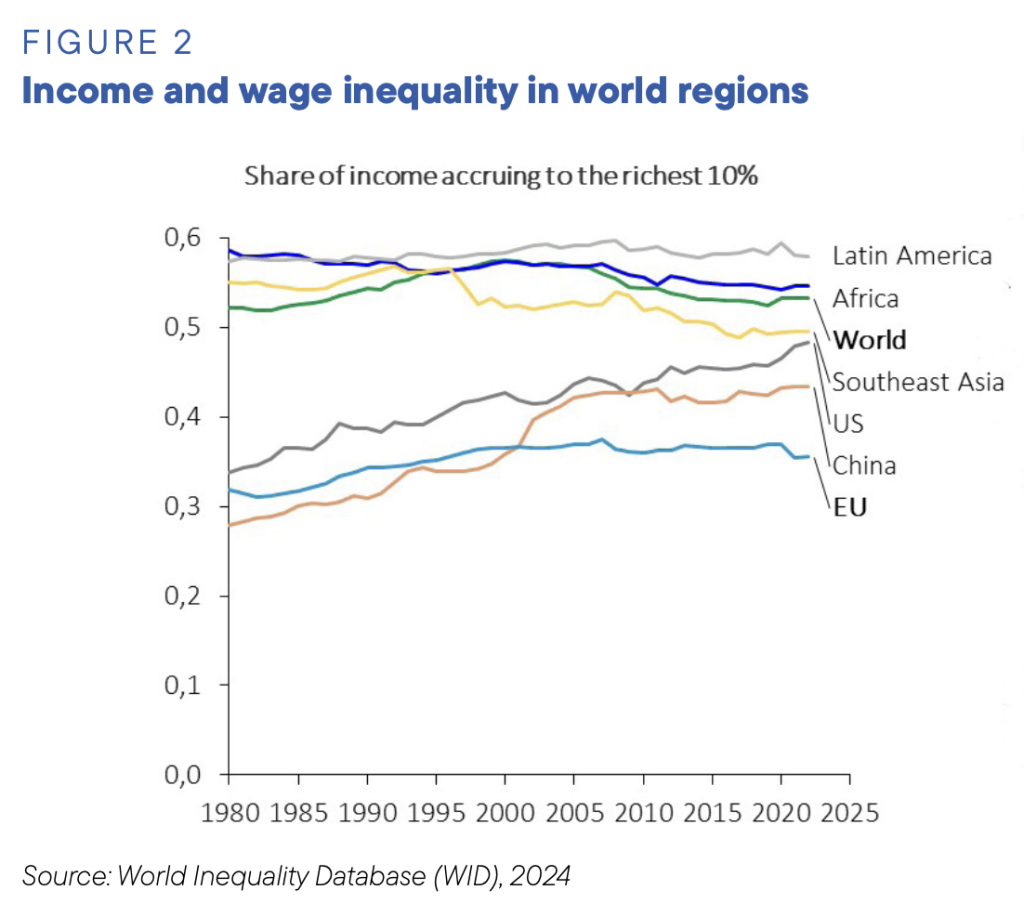

How about wealth inequality?

That graph there is probably as good an explanation as any to answer the question of why the EU elite want to follow the US model. For Ursula, Draghi and capital these are signs of being uncompetitive, and their solutions are coming: lower wages, a more flexible workforce (preferably machine), more private equity, more privatization, more asset-price bubbles, and more over-indebtedness for the bottom 90 percent.

In certain places in the EU, such as Italy, this process has been ongoing for decades dismantling what the communist party and trade unions helped build out of the rubble of WWII.

The good news is that’s typically a long tear down process (although the crises are coming more frequently nowadays). The EU moves methodically through the byzantine layers of bureaucracy and push and pull with national governments dealing with what’s left of the unions. That means there’s time to halt the march of financialization and reverse course. The bad news is it’s like boiling a frog who fails to notice the slow deterioration of quality of life until it’s too late.