Yves here. This is the second post we have run questioning the thesis that peak oil will set in before 2030. Here the argument is that key sources of overall energy demand have been ignored, and that demand will perpetuate fossil fuel use. Separately, the powers that be are trying to increase the use of electricity from solar panels without having addressed needed grid investments or how to address base load needs. This planning failure will also slow the shift away from oil and gas.

By David Messler, an oilfield veteran, recently retired from a major service company. During his thirty-eight year career he worked on six-continents in field and office assignments. He currently maintains an independent training and consulting practice, and writes on energy related topics. Originally published at OilPrice

- The IEA predicts peak oil demand in 2028 due to the shift towards cleaner energy technologies.

- OPEC disagrees, forecasting rising oil demand driven by increasing energy needs in emerging economies.

- Two key factors often overlooked in oil demand forecasts are the growth of the middle class in emerging economies and the energy demand for artificial intelligence.

It is fairly common nowadays to see relatively near-term estimates for a point at which demand for petroleum-based fuels begins to decline. The term often used to describe this “tipping point” is Peak Oil Demand. When I say “near term,” I mean right around the corner if you look at an estimate published last year by the International Energy Agency-IEA, an intergovernmental agency headquartered in Paris, France, and originally established after the Oil Embargo of 1973 to help cushion against future oil shocks. This agency has expanded its mission to a fairly broad remit over the years since, and it is not the purpose of this article to detail all its endeavors. One role we will highlight is that of the one it plays in gauging and advising member governments on energy security and energy sources for the coming years.

In that capacity, the IEA in a report entitled, Oil 2023, and published last year settled on 2028 as the year past which the use of petroleum fuels will begin to decline.

“Growth in the world’s demand for oil is set to slow almost to a halt in the coming years, with the high prices and security of supply concerns highlighted by the global energy crisis hastening the shift towards cleaner energy technologies, according to a new IEA report released today.”

This view is largely shared, particularly with respect to liquid motor fuels, by other agencies and organizations that produce long range estimates. The U.S. Energy Information Agency-EIA, Rystad, and Det Norske Veritas- DNV, all show this category tailing off rapidly in the 2030s as electric vehicles assume larger shares of passenger vehicles. We will call this the “Bear Case” for liquid fuels.

As you might expect the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries-OPEC, disagrees with this view. In fact in their recent report on oil demand outlook, published in Nov 2023, they see oil demand of all kinds, except for electricity generation, rising from ~105 mm BOPD in 2025, to 116 mm BOPD in 2045. This forecast show use of oil as a road fuel continuing to be the largest source of demand increase for this period.

The report notes that “the divergence between the IEA and OPEC outlooks is largely due to assumptions regarding the speed at which internal combustion engine vehicles will be replaced by electric vehicles.”

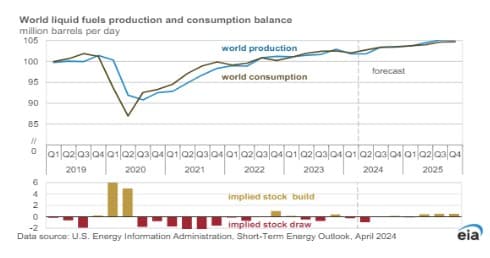

What is interesting is that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to see a production trend being established that would support the bear case. In the U.S., we are pumping at a rate of over 13.2 mm BOPD and still importing ~6.7 mm BOPD to feed our nearly 22 mm BOPD daily habit. The U.S. Energy Information Agency-EIA forecasts in their monthly Short-Term Energy Outlook-STEO that by the end of 2025, global production and demand fall into a fairly tight balance at 105 mm BOPD. That certainly isn’t a long-term trend, but as is often said, the long-term trend is made up of a bunch of short-term ones. For my part, I would say that the trend line in the STEO graph below matches the OPEC estimate more closely than the other three.

Both of these notions cannot be true. Which is the correct assumption about future oil demand? Or are they both wrong? What are two factors these two disparate views of oil demand are not taking into account?

The first answer lies in how you interpret the growth of the middle class in China, India, and Africa in terms of energy demand and the final form it will take. The second is the advent of energy demand for Artificial Intelligence (AI), an entirely new source of demand that is just now starting to appear in energy demand forecasts. I discussed one possible outcome of this demand for U.S. natural gas in an article in March 2024.

To be clear, I am not arguing that AI demand will directly impact crude oil demand as a primary source. Most analysts are factoring renewables and natural gas to meet AI demand. What will impact demand for WTI and other baskets of crude is the relationship to light oil production in the U.S. and the associated gas that’s produced along with it. We will leave that discussion for a future article and refocus on our basic topic. What could oil demand actually be when accounting for growth in currently underserved but upwardly aspiring lower classes?

Then there is the Bull Case for oil. Arjun Murti, a well-known energy commentator and partner at energy analyst firm Veriten, as well as a former Goldman Sachs energy analyst, discussed future energy demand in a recent podcast on his Super-Spiked blog. In the episode titled, “Everyone is Rich,” Arjun posits what the impact on world energy demand would be if everyone was as energy-rich as the “Lucky,” 1.2 billion people that live in the Western World. More specifically, Arjun asks what it would mean for the other 7 billion people in China, India, Asia, and Africa to have the lifestyle that Americans, Canadians, Europeans, and a few other countries enjoy. The answer he comes up with on an absolute basis, 250 mm BOPD, using a reference point of 10 bbls a year!

Where are we now? The U.S consumes ~22 bbls of oil annually per capita while China consumes 3.7 bbls per capita. Indians use just 1.3 bbls per annum. That’s a pretty wide gap, and as Arjun notes, “economic growth and energy growth are one and the same. You do not get economic growth without adequate energy.”

One of the arguments put forward by the Peak Oil crowd is that efficiency growth Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and energy substitution will bend the curve on oil demand, as noted in the 2030’s, and spell the twilight of fossil fuels. Arjun points out that there is simply no evidence this is happening using data compiled by Goldman Sachs through 2019. Efficiency gains never lower the amount of energy needed to produce an additional dollar of GDP, above 2.7% GDP growth. A point rarely hit in modern times. To close that gap and attain growth you need more energy inputs. Oil.

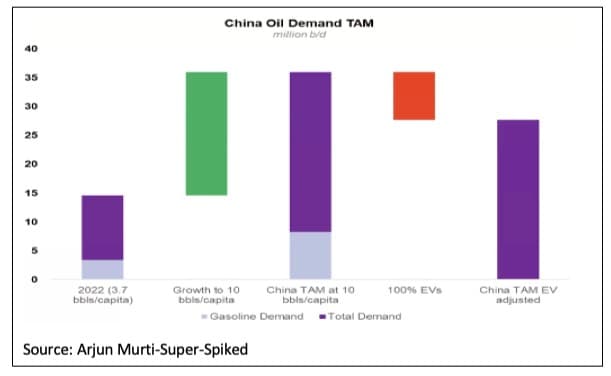

Looking at Arjun’s graph below, which uses China as an example, we can see with their present demand of 3.7 bbls per capita which equates to about 15 mm BOPD. With 10 bbl per annum added on for growth in the middle class, you get to 35 mm BOPD to meet Chinese energy demand. Even if China attains 100% Electric Vehicle-EV penetration, not something Arjun (or I) believe is possible, you still have 27 mm BOPD of oil demand. According to SP Global China produces about 4.1 mm BOPD, leaving a gap of about 11 mm BOPD they must import to meet present-day demand.

A point that leads me to what Arjun noted as the ultimate demand limiter and why, although countries that will surely desire to increase their oil usage may not be able to do so. Geopolitical limits to imports. Quoting Arjun, “There is no precedent for countries importing 20-30 mm BOPD” to meet their energy needs. The U.S., before the advent of shale production was importing over 10 mm BOPD as recently as 2005. That’s what we know is possible.

It should be noted that India is in a similar fix and for it to meet Arjun’s 10 bbl per capita standard for being rich, they must import 35-45 mm BOPD. We just don’t know if this can be done from both a logistical and sheer capacity of supply basis. As the EIA graph above highlights global oil production has increased only about 3 mm BOPD since 2019. In order for the world’s poor to become richer, a great deal more oil will have to come to market.

Your Takeaway

The message of the growth of the middle class globally often gets lost in the constant blare of climate change and energy transition noise. The fact remains that the world we live in today and the one likely to exist at mid-century, runs on oil.

The notion that the world can quickly and painlessly transition to other forms of energy has developed some, not holes, but gaping craters in recent times. Offshore wind farms are being canceled as costs mount. Car manufacturers are delaying implementation of EV rollouts due to lack of interest from consumers. Communities impacted by siting of solar farms are pushing back on land use as they propose to gobble up large tracts for this purpose.

Roger Pielke, another well-known energy commentator and author, in a post in his Substack, The Honest Broker, cites a White Paper by Vaclav Smil that discusses our energy transition progress to this point-

“All we have managed to do halfway through the intended grand global energy transition is a small relative decline in the share of fossil fuel in the world’s primary energy consumption—from nearly 86 percent in 1997 to about 82 percent in 2022. But this marginal relative retreat has been accompanied by a massive absolute increase in fossil fuel combustion: in 2022 the world consumed nearly 55 percent more energy locked in fossil carbon than it did in 1997.”

Balanced against this lack of progress in substituting oil for other forms of energy is the fact that the world’s energy supply is in a tight balance with demand at present. If the poor of the world make even modest progress toward Arjun’s 10 bbl per annum prognostication in the coming years, the Bull Case for oil will certainly asset itself.