Why did the stock market bounce this summer?

Everyone has their explanation: The Fed might pivot! Inflation readings have now peaked! Oil prices are down 25%! China is ending the lockdowns! The labor market is staying strong! Earnings are still coming in better than expected!

All true.

But there’s an even better reason that doesn’t invalidate any of the ones I’ve posted above. It allows them all to get the oxygen they need, individually, to appeal to the person clinging to them as their “reason” for what’s happening. We all need our reasons and explanations, after all.

So here’s my explanation, and, if you fancy yourself an intellectual or you’ve spent years at a fancy school, you will definitely hate it: The money has to go somewhere.

The stock and bond markets, in combination, form an equilibrium, absent severe changes in the money supply or the overarching needs of the investing public. There is stasis.

The Federal Reserve is talking about shrinking its balance sheet and bringing down the money supply. They’ve raised interest rates and are in the process of letting their $9 trillion portfolio of Treasury and mortgage bonds mature without replacing them with new bonds. They call this “the roll-off.” Great.

They also want to shrink the money supply to ease the demand for things and stuff in the economy and tighten financial conditions. There’s no evidence that any of this has actually happened yet in the data, but we’ll assume it’s probably underway.

Central banks around the world are all engaged in the same sort of adjustment to both current interest rates and market expectations for future interest rates. In Argentina, they have 64% inflation, which means you better buy the loaf of bread you might want on the dinner table when you wake up that morning. And don’t even think about handing a restaurant owner your credit card for settling a bill. Just throw a fistful of pesos on the table and run like hell lest the price of your entree should rise during dessert. This is an extreme version of what economies all over the globe are experiencing and reacting to.

As a result of the sudden inflation fight breaking out this past winter, the equilibrium of stocks and bonds has been disturbed. Buyers and sellers have had to adjust. They’ve spent the last few months adjusting. Not just with their holdings, but with their feelings, thoughts, emotions and expectations. And a new equilibrium is being reached. It won’t be final. This process is never finished. It’s an oscillation.

Oscillation is a to and fro, usually between two points, over a period of time. Up and down for example. Or left and right. Oscillations are made up of cycles. Pluck a guitar string and the result is a sound wave. The vibration is what produces the sound wave but it is not self-perpetuating. It ends as the oscillation peters out. The sound fades. You’d have to pluck it again for a new sound wave. This is what’s referred to as a damped oscillation. “Most free oscillations eventually die out due to the ever-present damping forces in our surrounding. The oscillation that decreases with time is called damped oscillation. Due to external factors such as friction or air resistance that results in damping, the amplitude of oscillation reduces with time, and this will result in energy loss from the system. An example would be the decaying oscillations of a pendulum.”

Volatility in the investment markets is a sort of damped oscillation in which the force that caused the volatility cannot be sustained indefinitely. The “damping” force that ultimately comes along and quiets the oscillation is investment demand. The money has to go somewhere. Buyers step in because they are in need of returns above what the risk-free rate of return can provide – eventually. They cannot stay on the sideline forever. Negatively-yielding sovereign bonds cannot be hidden out in indefinitely, regardless of prevailing attitudes or investment policy mandate or even government statute. Risk finds a way. The intermediaries who manage large pensions and portfolios – the people in charge of taking risk and producing return for others – will eventually find new things to do and new places to put the capital. Or the capital will be taken away and, with it, the potential fees. And nobody wants that.

So! This is why the stock-bond portfolio can trend in one direction or another for different lengths of time and to different magnitudes of gain and loss, but will eventually oscillate its way back to some equilibrium. Even if that equilibrium proves fleeting, a way-station rather than a destination.

There are damping forces everywhere in society keeping the oscillation of stock and bond volatility within an ever narrowing band, despite periodic headline-catching outbursts from time to time. These damping forces include demography (we’re living longer and in need of higher savings and returns on those savings), regulation (the arc of the universe bends toward increased safety and security), innovation (the ultimate dampener on costs, inconvenience and the unavailability of goods and services), the professionalizing and institutionalization of the investing profession (a hundred years ago everyone in stocks was a degenerate gambler with a margin loan, now just half of us are) and the advent of massive retirement systems (a hundred and fifty years ago you died plowing a cornfield or got shot in the street over an insult – that was your retirement plan). Each of these damping forces plays its part to reduce the length and breadth of the periodic vibrations produced by a given volatility-engendering event (a Fed speech, an earnings miss for a crucial stock, an errant North Korean missile, a disappointing election, etc). This reduces the overall oscillation we experience in our stock and bond portfolios overall.

So there is a big directional move like the one that jarred us all in the first half of 2022. And then we’re due. What was done is undone. Reversion. The pong to the previous ping. The zig to the zag. The yin to the yang. The cycle. The full oscillation. Trillions of dollars in search of a home. Hundreds of millions of investors at work, acting according to a trillion different time-horizon-and-goal combinations. The process proceeds regardless. And in this equilibrium-seeking process, we find a new space for that classic stock-bond mix of risk and security, upside and income, to breathe in.

And how do I know this is so? I have more than two hundred years of evidence on my side. The money has to go somewhere. It always has had to go somewhere. And we eventually find this equilibrium between the last thing that happened and the next thing that is about to. It’s hard to keep shocking us all with the same news. Better show up with something new. In the meanwhile, we’ll get busy getting used to whatever you just said. The oscillation can be dampened by boredom, too.

But 2022’s volatility has been incredibly unique for this era – we haven’t seen a plus 20% or minus 10% year for the 60/40 stock-bond portfolio since 1975 up until now. That’s two years before I was born. More on this in a moment.

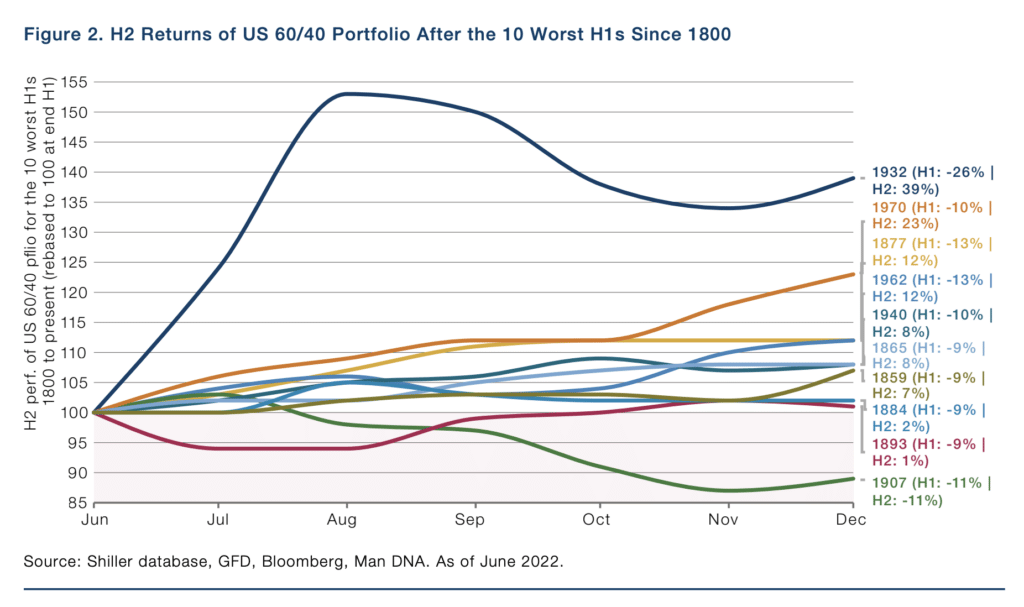

I’d like to show you something you may not have seen before. It comes to us via the Man Group (thanks Meb). In the first chart, we see that 2022’s first half was the second-worst for a 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds in over two centuries. Centuries. I’ll let that sink in for a moment. The researchers note that In 79% of years going back to 1800, a 60/40 portfolio was positive through to June. This year’s first half featured the worst 60/40 performance since 1932 and there were very few other years that have ever even come close.

This represents a severe disturbance of the pre-existing equilibrium. But again, risk finds a way.

So here’s what has historically happened next…

Bounce.

The 60/40 has historically come roaring back in the second half of all of these years save for 1907, a year we usually associate with “the Panic of” when we’re referring to it.

Man Group says “In the ten worst H1s (excluding 2022), average performance was -12%. For the corresponding H2s the average was 10%, and the positive hit rate was 90%.”

It’s not that the second half has to be better than the first half, it’s just that it almost always is. You can go back and read newspaper headlines to try to piece together the reasons for the bounce. Seek and ye shall find. There will always be something to pin the market action on retroactively.

Or you can accept my explanation for the legendary durability of the 60/40 stock bond portfolio over years, decades, eras and entire centuries: It has to go somewhere.

The oscillation will continue regardless of whether or not you want to accept its existence.