The marked disappointment of the Arthur Ashe Stadium crowd, when Serena Williams hit her final forehand into the net, did not linger for long.

A rousing acclamation soon rang around the stadium for a woman who extended Ajla Tomljanovic into a fourth hour in their US Open third-round match, and whose brilliance spanned more than a quarter of a century.

She and her sister Venus changed the game, and the approach to life of many – whether they had been dreaming of a pro tennis career or simply a better, fairer future for themselves and their family.

Be yourself, was the message. Women, especially those of colour, do not need to hide their emotions or a desperate will to succeed. Many noses were put out of joint in the process, but corrective surgery had been long overdue.

Muhammad Ali and perhaps Billie Jean King aside, has any athlete made a greater impact on society than Serena Williams? And she may be only just beginning.

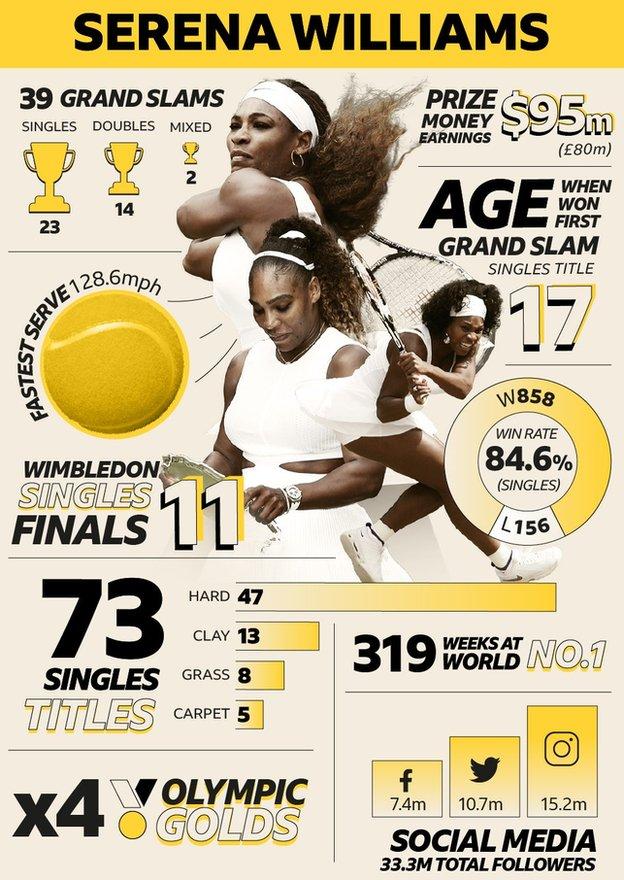

Her achievements are without parallel. Margaret Court’s all-time record of 24 Grand Slam singles titles was always a false target, as the phenomenally successful Australian won 13 of those titles when professionals were banned from taking part. The target was, though, incredibly motivating and helped a 30-plus Williams win more than half of the Slams she entered between Wimbledon 2012 and the Australian Open of 2017.

No-one else has been able to keep collecting Grand Slam singles titles over an 18 year period. Twice, 12 years apart, Williams won all four in a row. The first ‘Serena Slam’ was completed at the Australian Open of 2003 and secured over four consecutive finals against Venus. The sister, who in Serena’s words was “taller, prettier, quicker and more athletic”. The sister, who had inspired the glowing newspaper articles and was originally the main focus of their father Richard. The sister, whose bed she sometimes had to share as a child but from whom she learnt so much and gained so much of her drive.

Williams won a total of 23 Grand Slam singles titles, despite only winning two in a five year period in her mid-20s. During what has often been the peak years of a player’s career, Williams was trying to come to terms with the death of her sister Yetunde in a drive-by shooting in Compton in September 2003.

In her 2009 autobiography Queen of the Court, she talks about slipping into depression. “It was an aching sadness, an all-over weariness, a sudden disinterest in the world around me – in tennis, above all,” she wrote.

She did not return to the top of the world rankings until five years after her sister’s death.

The arrival of Serena and Venus accelerated the spread of power hitting throughout the women’s game. Monica Seles and Lindsay Davenport had started the ball rolling, but this type of aggressive hitting had not been seen before.

The former world number six Chanda Rubin recalls a match she played with Serena in Los Angeles in 2002.

“She hit a shot and it was the hardest forehand I had seen go by me,” she says.

“I didn’t even have a chance to react and move to it, and I had played Steffi Graf, Monica Seles, Lindsay Davenport and Jennifer Capriati.

“This was just pure power. And from zero to 60. That visual never left me, even though I won that match.”

Williams also possesses arguably the greatest serve of all time. It offers power, placement, rhythm and accuracy, and is harder to read than War and Peace.

As both a woman and a woman of colour, Williams’ achievements and attitude have made a dizzying impact on so many others.

“Before Serena came along, there was not really an icon of the sport that looked like me,” Coco Gauff said in New York last week.

“So growing up I never thought that I was different because the number one player in the world was somebody who looked like me.

“Sometimes being a woman, a black woman in the world, you kind of settle for less. She never settled for less.”

Do not forget the Grand Slam title won in Melbourne while eight weeks pregnant, and the four Grand Slam finals she subsequently reached as a mother in her late 30s. Do not forget the postnatal depression, and the two pulmonary embolisms which endangered her life.

Williams knows only too well that black women are much more likely to die in childbirth and addressed the matter in a BBC interview in 2018.

“Doctors aren’t listening to us, just to be quite frank,” she told me.

“There’s some things we are genetically pre-disposed to, that some people aren’t. So knowing that going in, or some doctors not caring as much for us, is heartbreaking.”

Williams has spoken out with increasing confidence on sensitive issues as her career has progressed. She chose 2015 to return to Indian Wells, where 14 years previously she had experienced an “undercurrent of racism” before the singles final against Kim Clijsters.

She cited former South Africa president Nelson Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom as having a significant bearing on her decision to return.

“I’m looking forward to stepping out and letting the whole world know that it doesn’t matter what you faced – you can just come out and be strong and say I’m still going to be the best person that I can be,” she said in California that March.

Serena Williams is, of course, no modern-day saint. Arthur Ashe Stadium has witnessed her six US Open titles, but also some venomous behaviour towards officials, for which she showed little contrition.

But I think she is the most remarkable athlete of the last 40 years.

The pain she feels at having to leave the stage will be shared by many in all corners of the world.