Yves here. Back in the day, workers were less compromising. The word “sabotage” does originate with factory laborers messing up production to thwart factories, as in automation, but not the throwing shoes into machinery version. From Wordfoolery:

Sabotage entered English in 1907 as a borrowed word from French. The French word derived from the verb saboter (to sabotage or bungle) whose origins lie in footwear. The sabot was a wooden shoe (from around 1200s) worn often by lower class workers as they toiled through muddy streets. They were clunky things but their thick soles got you above the level of the dirt and they were cheap to make, albeit wobbly. The wealthier might wear them too, but they would change into fancier leather or silk shoes when they reached their destination.

The sabots were pretty noisy objects, everybody would hear you coming and saboter translated literally as to walk noisily in sabots…

You might assume that the source of sabotage’s modern meaning is that the disgruntled would destroy property by throwing shoes at it (we know it’s way to express disrespect in Iraq, for example). I suspect a shoe in a factory machine would bung up the works pretty well. Sadly there’s no evidence on the whole shoe-chucking notion. Sabotage was used in French for all types of clumsiness – from wobbling along on wooden shoes to playing music badly. It’s reported in 1907 as being a workman’s way of protesting – instead of striking they would work badly, annoy customers, and cause a loss to their employer.

Grammar Phobia debunked the sabot throwing theory beautifully in this piece and adds the information that rural workers wearing sabots were sometimes mocked for being as clumsy and slow as their footwear. This led to sabotage being a type of “go slow” work protest in the late 1800s in France.

The post below indicates that modern employees worried about automation don’t attack or undermine workplace operations but try to bargain for more of the pie, either at the job via unionizing or via more generous government policies.

By Marta Golin, Postdoctoral Research Associate University of Zurich and Christopher Rauh, Professor University Of Cambridge. Originally published at VoxEU

Automation can have important social and political consequences, as well as large impacts on the labour market. This column provides experimental evidence on the causal link between perceived automation risk and workers’ employment responses, preferences, and attitudes. The authors find that fear of automation leads workers to demand higher taxation and more redistribution. Workers plan to join a union to protect their employment rather than adopt new skills or switch occupation. The findings highlight the pressure that automation may put on public budgets, and provide new insights into how technological advancements may alter the political landscape.

Increased automation and the use of robots and artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to drastically change the nature of work, and whilst new jobs may be created that are complementary to machines and algorithms, future automation also poses a threat to the existing jobs of many workers (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020). Labour displacement due to automation can have important social and political consequences, as shown by the impact of past technological advancements (Caprettini and Voth 2020). The threat of future automation waves is therefore likely to play a critical role in shaping workers’ response, the public discourse around economic inequality, and the role of the government in mitigating its effects. Despite the importance of understanding the link between the perceived threat of automation and workers’ responses, research on this topic has been held back by the difficulty of identifying exogenous sources of variation in perceived automation risk. To fill this gap in the literature, in a new paper (Golin and Rauh 2022), we provide evidence on the effect of fear of automation on workers’ behaviour, intentions, and preferences from a sample of almost 4,300 workers in the US.

How Workers’ Fear of Automation Relates to Preferences, Attitudes, and Intentions

How concerned are workers about the threat that automation poses to their jobs in the near future? To measure workers’ perceived automation threat, we ask respondents to estimate the probability that, in the next ten years, they will lose their job/not find a job due to automation, robots, or AI. Our data show that workers in our sample are on average concerned about automation, with almost 40% of respondents believing their probability of being replaced by a machine, robot, or algorithm to be higher than 50%. Younger respondents and the less educated are amongst the most concerned groups, and fear of automation is highest amongst respondents working in occupations related to food preparation and serving as well as transportation and material moving. Those least in fear are working in protective services or community and social services.

We then proceed to examine the correlational relationship between perceived automation risk and workers’ preferences, attitudes, and employment responses. Workers can insure themselves against the automation threat by demanding more redistribution from the government, or by reskilling and changing occupations. Understanding the link between fear of automation and workers’ preferences and behaviour is important to predict the societal consequences of future automation waves. In our survey, we measure workers’ responses to automation with a series of questions capturing (1) preferences for redistribution; (2) workers’ support for government spending towards adult training programmes and income support programs for the poor; (iii) workers’ employment responses, as measured by their intentions to join or remain part of a union, join a retraining programme, or switch occupations; (iv) populist attitudes; and (v) voting intentions.

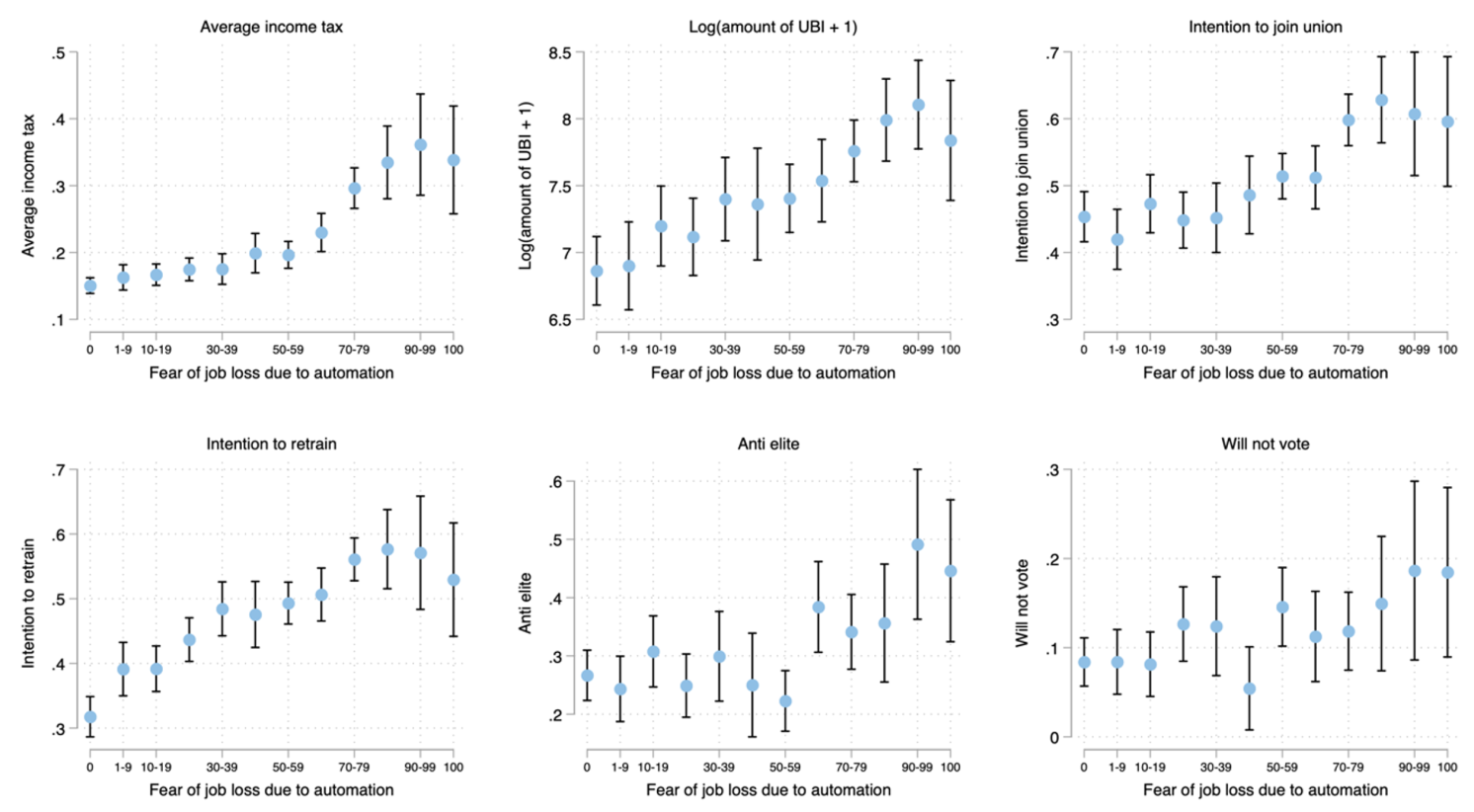

We find that perceived automation risk strongly relates to workers’ preferences for redistribution, employment responses, and populist attitudes. In Figure 1 we show, for example, that workers who are more concerned about the automation threat to their job favour higher income tax rates, request higher universal basic income, are more likely to be looking to join a union, are more likely to want to retrain, are more likely to consider themselves anti elite, and are also more likely to abstain from the next presidential elections.

Figure 1 Fear of automation and preferences, intentions, and attitudes

Notes: The x-axis shows the binned perceived probability of losing one’s job due to automation within the next 10 years versus average outcomes indicated in the title and on the y-axis. The sample is restricted to the control group. Thin lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

The Causal Effect of Fear of Automation

The above relationships between perceived threat of automation and workers’ preferences, intentions, and attitudes cannot be interpreted causally because the same factors that might be driving automation risks might also be driving opinions. To overcome endogeneity concerns, we use an experiment that we embed in our survey which allows us to affect workers’ beliefs about the threat posed by automation. After eliciting respondents’ perceived fear of losing their job due to automation, participants of our study are randomised into either a control group or one of two treatment groups. While respondents in the control group did not receive any information, treated participants were informed about the average expectation of job automation of other labour force members working in similar jobs as theirs. The figures provided were derived from data collected as part of the Covid Inequality Project (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020), which featured information on the perceived automation risk of a representative sample of members of the labour force in the US.

Fear of Automation Increases Demand for Larger Welfare State and Alters the Political Landscape

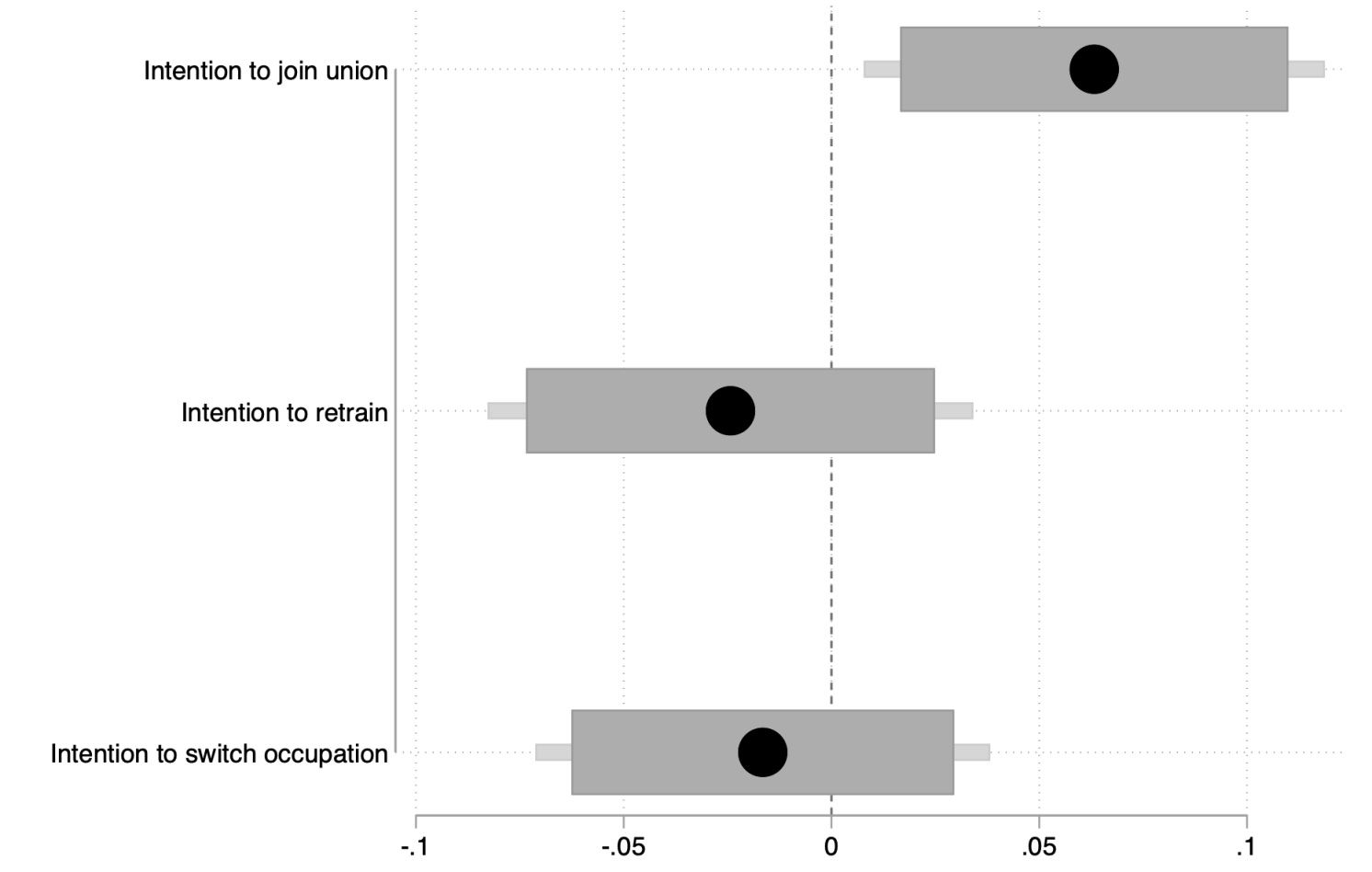

Results from our information experiment show that receiving information on expected automation leads to some significant changes in workers’ preferences and attitudes. However, we do not find any significant effect of fear of automation on intentions to switch occupations or participate in a retraining programme. Economic models looking at optimal taxes assume that workers respond to automation by adopting non-routine skills (Rebelo et al. 2020). However, the only causal effect on employment responses that we find is a much higher likelihood of intention to join a union when exposed to a job loss probability that is higher than one’s initial fear (see Figure 2). This is suggestive of the fact that workers will not respond to future automation waves with re-skilling or switching occupations, but will rather seek job (and task) protection through a union. In terms of the political landscape, automation risk also causally reduces workers’ intentions to turn out to vote at the next presidential elections and shifts their political ideology to the left.

Figure 2 Treatment effect on employment responses

Notes: The figure plots the coefficients of the treatment intensity. The outcomes on the y-axis are workers’ intended employment behaviour. Thick lines indicate the 90% and thin lines the 95% confidence intervals.

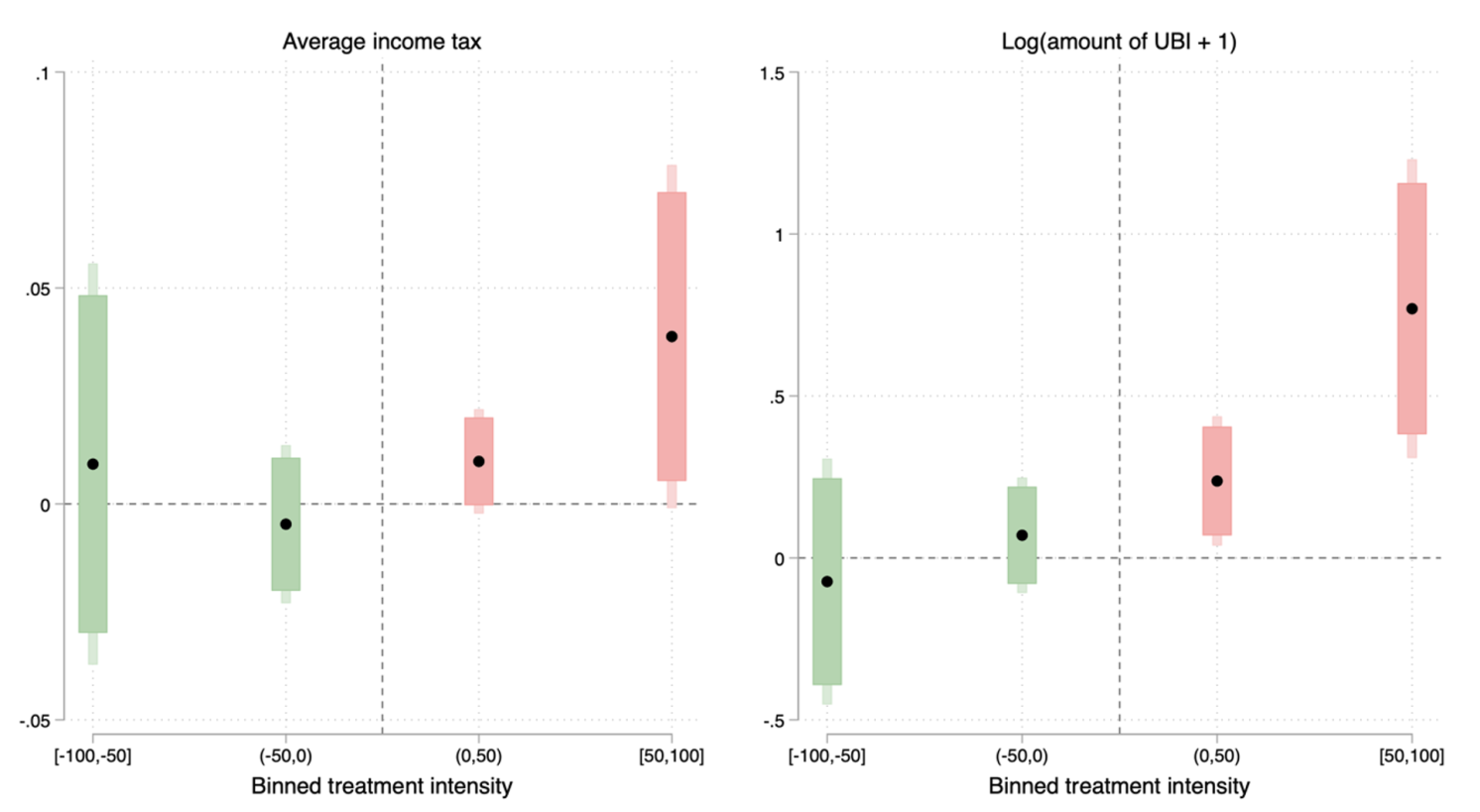

Figure 3 shows how respondents’ preferred mean tax rate on income (left) and level of universal basic income (right) change depending on the intensity of the information treatment they received. The green bars represent the treatment effects on workers being informed about good news, i.e. lower job loss probabilities than they feared. The red bars display treatment effects of bad news, i.e. workers being informed about a higher job loss probability than they expected. The fact that the far-right red bars – the treatment effects of receiving very bad news – are largest indicates that workers informed about much higher job loss probabilities request higher taxes on income and higher levels of universal basic income. Overall, we find that for most cases, treatment effects are not symmetric. The treatment effects tend to be driven by respondents who saw an automation probability that was higher than the level of fear they had.

Figure 3 Treatment effects on preferred taxes and UBI by treatment intensity

Notes: The figures plot the sum of the coefficient on the treatment dummy and the dummy capturing the intensity range indicated on the x-axis. The outcomes on the y-axis are the mean tax rate on income and the log of the preferred level of UBI + 1. Thick lines indicate the 90% and thin lines the 95% confidence intervals.

Taken together, the results from our survey experiment raise concerns about the potential for future automation waves to put pressure on public budgets through increased demand for redistribution and a larger welfare state. With democracy already on decline (Frey et al. 2020), we find that automation has the potential to stir anti-elite sentiments as well as reduce voter turnout and trust in politicians. Given the pending waves of automation, in particular in the service sector (Baldwin 2022), policies need to carefully consider how to prepare workers for, and accommodate those left behind by, the changing landscape of work.

See original post for references